Improvisations on Some Very Big Themes

Ruben Nusz weighs in on two high-minded exhibitions currently on view, focusing on work by two philosophically inclined artists: Isa Newby Gagarin ("Beru," now at Midway) and Kris Martin (part of the Walker's "The Quick and the Dead" group show).

Kris Martin at the Walker Art Center’s The Quick and the Dead, on view through September 27

Belgian Kris Martin, one of the myriad artists featured in the intellectually energetic exhibition The Quick and the Dead at the Walker Art Center, pursues epistemology like a scientist with a poet’s heart, distilling themes of entropy, time, and death into stirring sculptures and contemplative performance pieces.

For Anonymous II Martin buried a human skeleton, originally donated for medical research, somewhere on the Walker grounds; if you’d like to pay your respects, a certificate in the exhibition discloses the GPS coordinates of the grave. This elegiac work neatly transmutes the rational into ritual; and, at the same time, Martin’s humane symbolic gesture infuses the historically chilly domain of conceptualism with true empathy, perhaps even sentimentality.

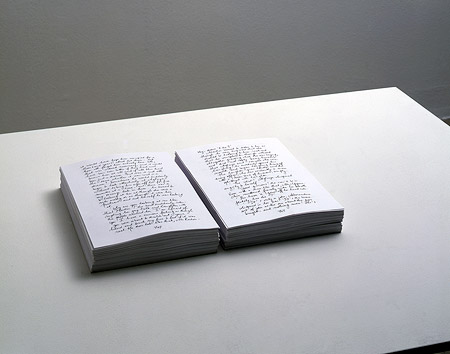

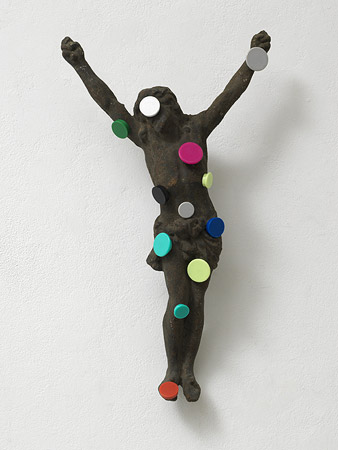

This isn’t new territory for the artist. In other works not featured in the Walker’s show, Martin further investigates the perennial human entanglements of truth and knowledge with death, that greatest of unknowns. For an exhibition at MOMA’s PS1 in New York, Martin reproduced the famous ancient Roman sculpture Laocoon and His Sons in plaster, but minus the deadly serpents (Mandi VIII). For another work, Martin transcribed, in longhand, Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot, substituting the name of the book’s protagonist throughout with his own. Martin, like Shakespeare, transcribes the greatest metaphysical questions of humankind into physical, accessible works.

The distinction between Martin and other artists tackling this theme — his similarly death-obsessed British peer, Damien Hirst, for example — lies in the intimacy of his sensibility, the humane touches that run throughout Martin’s body of work. Rather than merely exhibit a nameless skull encrusted with diamonds to make his point, for instance, Martin enlisted the assistance of medical technology to scan his own head using 3D composite imaging. He then used that information to fabricate an exact replica of his skull in silver-plated bronze. The resulting piece, entitled Still Alive, stands as 21st-century memento mori and, at the same time, as a humanist monument both to science and self-reflection.

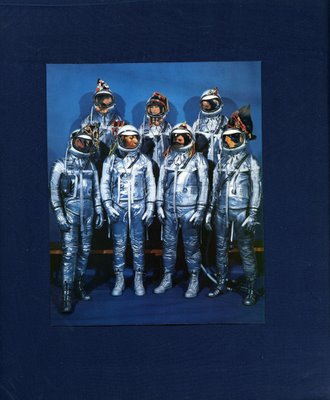

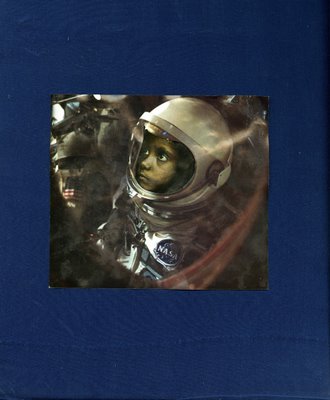

Martin’s artwork exemplifies the pop conceptualism featured in The Quick and the Dead. Taking its inspiration primarily from 1960s conceptualism (especially the art of Robert Barry), most of the work in the exhibition investigates the boundaries of established definitions of art objects themselves while, at the same time, examining the broader metaphysical perimeters of human thought and experience with many physical objects as evidence. As happens with virtually all conceptual art exhibitions, The Quick and the Dead unavoidably relies too heavily on wall didactics to contextualize the artworks. Nevertheless, eloquent curator Peter Eleey has forged an exemplary, lyrical selection of work that — like the sculptures of Kris Martin — surveys notions of space, time and beyond, but does so in personal terms and on human scale.

________________________________________________________

Isa Newby Gagarin, Beru (main gallery); Patricia Esquivias, Reads like the Paper, 2005-2009 – both shows on view at Midway Contemporary Art through June 20

My candidate for gallery show of the year — yes, I’m aware it’s only May, but this exhibition of work is that good — is the one currently on view at Midway Contemporary Art in Minneapolis. Isa Newby Gagarin and Patricia Esquivias address themes of isolation, multiculturalism, American imperialism and, in a way, Nicolas Bourriaud‘s new concept of the altermodern (defined loosely by wikipedia as “art made in today’s global context as a reaction against standardization and commercialism”).

Gagarin — a precocious young artist who, just last year, graduated from the Minneapolis College of Art and Design — offers a subtle critique of the insidious condescension that pervades the Western gaze upon less affluent cultures in developing parts of the world, especially tribal communities. Specifically, she addresses the pernicious First-World tendency to cast these societies as inferior “others” while, at the same time, freely co-opting and repurposing elements from their cultures. Modern art is rife with examples of artists assimilating the visual tropes of non-Western peoples while ignoring the symbolic, oftentimes religious meanings associated with the iconography (e.g. see Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon).

Consider the piece Turn, Turn: here Gagarin has assembled a series of National Geographic images of women from a variety of non-Western cultures, representative of all skin shades; some women are wearing the multi-hued textiles popular in West Africa, others featured in the photographs are adorned with the neck coils favored in parts of Indonesia and South Africa, and still other women pictured are simply naked. An electric fan pointed at the images literally animates them; the pictures vibrate, forcing the viewer to look more deeply, resuscitating lifeless clichés into breathtaking depictions of real women.

Elsewhere are Gagarin’s minimalist collages, created on large, lowbrow newsprint books using strategies of “doubling, division, transference, and accumulation,” according to the gallery’s didactic materials. Instead of just combining images to create her collages, Gagarin cut small sections out of found sources and glued them to the large newsprint pages. This treatment of the material effectively narrows our attention to her deeply personal and decidedly complex, ethnological concerns.

One such “book” features temporary tattoos of tigers overlaid on images of unnamed “tribal” peoples. The combination of the two eloquently evinces the destructive aftermath of Western hegemony and militarism for the cultures left in the wake of colonialism. Seeing them, I thought immediately of the tangled legacy of Rudyard Kipling, renowned author of The Jungle Book who was later critiqued for endorsing British Imperialism with his fiction and poetry.

Another of Gagarin’s book collages reveals an image of a white male fashion model wearing a wool coat and polychromatic zebra-striped, “tribal” looking pants: an unmistakable, clever visual representation of cultural pillaging for the crass cause of capitalism. After flipping a few pages in this specific book, we see animal images (a snake eating a rat) followed by a small portrait of the artist herself.

Born in Guam and spending her childhood years living in Texas, Alaska, and Hawai’i, Gagarin is the quintessential altermodern artist in the age of Obama. And alongside the exquisite video narratives of Caracas-born artist Patricia Esquivias, Gagarin provides us land-locked Minnesotans with an insightful, delicate, and emotionally moving tour de force exhibition of work.

*****

Noted exhibitions:

- The Quick and the Dead, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, on view through September 27

- Beru: Isa Newby Gagarin (Main Gallery) and Reads Like the Paper: Patricia Esquivias, both solo exhibitions on view at Midway Contemporary Art in Minneapolis through June 20

About the author: Originally from South Dakota, Minnesota artist Ruben Nusz was raised by cowboys and later graduated Summa Cum Laude from the University of Minnesota. In 2003 Nusz directed a feature-length documentary that toured the festival circuit. He has exhibited mixed-media works at the Minnesota Museum of American Art, Rochester Art Center, Rosalux Gallery, Umber Studios and the Hopkins Center for the Arts. He is one of the co-founders of SELLOUT Gallery, an artist-run space devoted to the exhibition of work by emerging and mid-career artists as well as independent curators.