If Care Is Essential

Dance artist Anna Marie Shogren considers how the current pandemic has cast care work in a new light, and suggests how we might create new myths of cultural production by tuning into a felt aesthetic and valuing our interdependence.

Anna Marie Shogren, Work / Lifelong Choreographies (2019). Installation of wearable pieces emulating conditions common in the aging body, enlivened here by Anat Shinar, Megan Mayer, Non Edwards. Photo: Isabel Fajardo.

“Artist” has been a man, a solid being, white, intact, untouchable, expensive. And a person that grows and produces another being, a person whose matter divides and exchanges? Or a person of any gender whose time for art is only what remains after caring for others? For these people, space for thought becomes public space. This body is work. Now, too, in the midst of a health crisis, nearly all work is of the body or for the body. And care is the word of the day. Essential work is draining, risky for the worker—though the person who emerges from the grocery store, from the touch of the working body, gains strength from this cooperation. A felt aesthetic more than a visual one. The pathways of emotional attention from those who relieve us of our waste have been hard to see.

That is what has been—but now, the siren sound of our interdependence wails in empty streets, in cluttered rooms where toddlers demand attention while parking tiny ambulances and recycling trucks. A desire to help is evident in the numerous Zoom offerings, so many of which appeared without expectation of return, of instant karma. “How are you in this challenging time?” “May this find you in peace and health,” we are saying. My bank has been saying. Compassionate words are popping up where generic, legally impenetrable speech had been. Sidewalks are expanding to serve people protected by masks, not metal machines, and they are carrying chalk messages encouraging feet to move forward. People are speaking and listening. Papa, don’t preach, we know what we’re saying.

Underlining this caring talk may seem fool-hearted, young. But we are home before dark, tracking a sense of culture and community by briefly glimpsing between the blinds. Our helping may only be an illusion, but rainbows have nothing to hide. Whether near or at a distance, supporting another’s safety, comfort, and nourishment, keeping another alive, has not been considered art. It has hardly been seen. And now?

Those safe at home seem to be responding, to be coping with worry and unoccupied time by developing or nurturing a practice: writing a poem a day, intimate photo journals, raw dance films, or taking long, unguarded naps. There is innate, unmanufactured, creative instinct at the surface of our skin. A more actual embrace of self-care. Caregivers too have long been joining art and healing. A CNA in a senior care residence who I spoke with last year said she often sang and danced with the residents while assisting them: “It gives me more energy to work, it’s just my habit.” A resourceful practice when the demand is greater than the supply.

Perhaps, this sensitive energy has already been rising. There has been significant destruction managing us, albeit unequally, for some time. Healthcare has not been a right. “Can you manage?” questioned the short-handed nurse. The focus on care in the art world has been, like the lungs in community-based Chinese medicine, breathing in courage and breathing out sadness for a while. Maternal art has taken a name for itself, having preceded and succeeded both social practice and relational aesthetics. For ages, reproducers have not been considered artists. Reproducing was not producing. In 1938, the novelist Cyril Connelly pronounced that “there is no more somber enemy of good art than the pram in the hall.” As if a mother’s mind is so diluted by concern for her child she cannot possibly create anything to provoke thought. Or even to be allowed the privilege to see art. And yet, she could lift a car crushing her child.

In the 1970s, Mierle Laderman Ukeles distinctly defined the art of maintenance and committed herself to the emotional support of many, including as an artist-in-residence for New York City’s Sanitation Department (notably, for zero pay). Michael Bramwell was—as art, as practical support—cleaning the floors of Harlem apartment buildings in the late 90s. So much more of this necessary and unsalable art is forging through now, largely because of the sheer will and innovation of the artists. Lise Haller Baggesen, tapping a disco era ethos in her plush installations, heads the Mothernist movement, which calls out disdain for the maternal body in the contemporary art world, a bias intersecting with sexism, ageism, and ableism. Enemies of Good Art and Prams in the Hall are parent-artist collectives that encourage conversation and ease process by welcoming children into rehearsal or studio spaces.

Being a woman, and/or having a womb, is not a prerequisite to create in this way—nor is it a pre-existing condition. Julia V. Hendrickson describes a Mothernist (after Haller Baggesen) as a person “with an inner capacity to care for someone, or something else, and to fight for those who cannot fight for themselves.”[1] This movement acknowledges the original seat of human life, and leans into care and social justice in the style of herd immunity. Devoted son and artist Peng Wu recently showed Daydream Chapel at the Weisman Art Museum while working in collaboration with sleep researcher Michael Howell. The work made an alternative environment for sleep therapy or knowledge transfer on the culture of sleep, giving audiences a place to lie peacefully near one another under a soothing textile peak. Newborns similarly regulate breathing and strengthen their parasympathetic nervous system by lying with loved ones.

vimeo://v/395968936

Laura Vail, Contemplation of Rest (2019).

Wu also works with CarryOn Homes, a collective of five whose work centers around belonging and immigrant and refugee experiences—content that relates to familial lineage and care. And although only two members are parents, the group often works with a very young presence in the room. Preston Drum, who regularly brings his young son to meetings and installations, highlights the benefits: “He’s having this amazing and unique experience, and whenever anyone came in the room he would greet them with a smile and a hug, diffusing the stress associated with the chaotic installation process”—yet he’s sure many would object if the little one expressed too much need. Aki Shibata also spoke of judgment around a parent’s investment: “I think there are perceptions about how you can’t do as much with kids. And that might be true, but at the same time, since [my first child] I work harder and I am more focused when I get to have my own time.” Both artists noted openings: the openness of their children, as well as the opening of eyes to ways to be within, and work within, the world. The collective’s work Living Room is currently housed in the When Home Won’t Let You Stay show at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. The room is a space for rest and relaxation, an offering to those disenfranchised—though the doors will stay closed for the bulk of the exhibition.

Queens-based artist and mother Heather Garland spoke to the benefits of having extra time while sheltering in place: a life suspended from juggling art, a job in the service industry, and caring for a young one. She noted that in average conditions, artists with financial security have a leg up, because their attention is less divided—but there is a “weird sort of leveling” now. “I don’t have any shows coming up, and no one else does either.” Right now, there is simply less to push one’s way through.

A mother labors through birth to realize the work of parenting starts immediately: no nap, no recovery. “Nothing will ever be the same,” are the cliche words that fall from new parents’ mouths. Then you stay in, sterilize everything, and think about food, while remaining highly aware of whether your actions will give your child a good future.

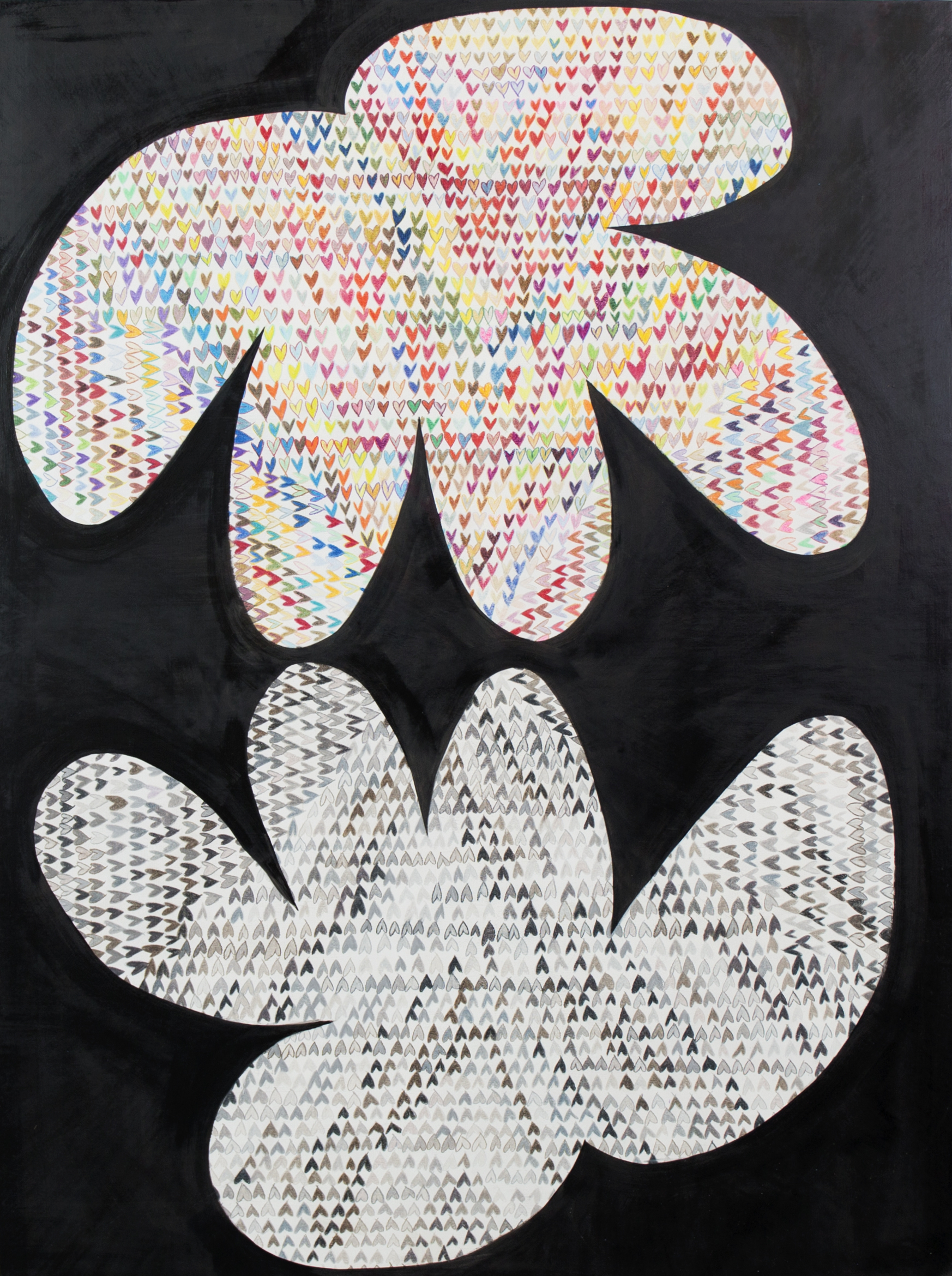

Heather Garland, Narcissist/Mirror (2015).

And now, take a moment to remember your own birth. You were there. It was extreme, beyond anything you thought you would know or could imagine. Your dependence was complete. Your existence was precarious, though some of us were more vulnerable than others, even in this first moment. You’ve come a long way since then. But now? This is beyond anything. Like nothing I’ve known, nothing we’ve known. I know nothing. But I’ve been thinking of you? If there is anything you need?

Jerry Saltz recently posted a Roz Chast cartoon about a fear that we had all woken up suddenly old, perpetually indoors, afraid of shopping. But I hear a calm and widened perspective in the voice of my grandma when we talk on the phone, the only access to loved ones available to most individuals in residential care now. I don’t yet know all she has learned. I know greed has failed this generation, that residential care businesses will soon be bankrupt because CEOs make six figures. The threat to care workers is startling and the care is greatly suffering. I hope it is the opposite—that we are young, starting anew. The wheel so needs reinvention. A chance to include more voices in the design, to teach the kids to read, to talk to Rufus while he’s still young.[2]

A group of feminist activists in Madrid, Precarias a la deriva, propose to elevate care work through a care strike, to break the “rigid order of threat”. But it is broken now. Isabell Lorey writes, “The care strike applies to political and economic dispositions that devalue care as being private, feminine and unproductive, therefore depoliticizing it. These are perspectives through which care work is perpetually made invisible, so that its associated conflicts are consequently not perceived.”[3] Are they perceived now?

Peng Wu, Daydream Chapel (2019). Photo: Peng Wu.

The podcasters of Literary Disco suggest looking to the trickster myths. A trickster is a cultural transformer, a character lusty for destroying and creating, with an ability to cross boundaries and beat interminable rules. “Artist” is also frequently mapped onto this character. A consistently male archetype—yet I can feel the agitation kicking inside of me too. More likely, I am the wild mover, taking up as much space as I can, dancing and Zooming in my attic “studio”. Lewis Hyde, poet and sociologist, likens America to the archetype of the con man, a trickster who takes advantage of those who bear empathy and trust. In 1998, he wrote that if we believe America to be “the land of opportunity, therefore opportunists, the land where individuals are allowed and even encouraged to act without regard to community, then trickster has not disappeared. ‘America’ is his apotheosis, he’s pandemic.”[4] It is time for a new myth.

We know what has been. We are in trouble deep. Capitalism is dying, and along with it the independent art genius and his material goods. With production momentarily suspended, we have been given time to sense the world without. We can dance like no one is watching, reaffirm a hunger for watching the body, movement, touch—our first and most immediate way to ask for what we need and don’t need. With these daily practices glimmering through technology, the more socially responsible, improvised, available—maternal—art culture is showing itself. We can look to the experiential, collaborative, and often participatory elements of this genre for ways to adapt to the separation of bodies. If you keep looking, they will be leaders as we return to public space. Marcus Young’s Don’t you Feel It Too?, a public improvisational dance practice for releasing one’s most honest self, is holding modified practices online, and is always available for use within personally adapted parameters. AUNTS out of Brooklyn is well into a chain curation of very conversational performances live on Instagram daily. I watch silently while trying to help my kid to nap. Whether the content is caring or escapist, the way art is now fusing with our daily moments is making the art world less of an elite world, less institutional, more generous and attentive to our needs.

In my head, everything is swirling, disordered. Everything is touching. Work, as I have been told to understand it, is nowhere in sight. But we are beginning to define, and certainly to depend on, the work we can never be without—including a healing movement of art. It is weird, and it is an opportunity to feel something brand new. For a moment, we are on another plane—though I know that change is coming like a teenage driver. In a week or two, I will look at this writing with the embarrassment of youthful indiscretion, the way I look at dances I made in undergrad. Most of our grief is ahead of us. We are vulnerable, fragile, unsure: babies. Babies having babies. Knowing what has been, projecting how artists’ and how caregivers’ lives will be affected by the pandemic in the long term seems pointless. Still, we will have a beautiful springtime. A child’s confidence in defining the world draws from an eagerness to learn, not arrogance. Now, before us: is it a pile of dirt or a cake? Time to make a cake.

Anna Marie Shogren is a dance artist whose continuing body of work centers around caregiving and the use of dance and touch therein, researching this work most recently as an Art and Health Resident at the Weisman Art Museum, working in collaboration with the University of MN School of Nursing. Based in Brooklyn for many years and residing in Minneapolis, her dances and dance-based installations have been seen at WAM, the Art in Odd Places Festival, Northern Spark, Danspace, Movement Research at Judson Church, DNA, AUNTS, Catch!, Radical Recess, Dixon Place, Gowanus Ballroom, St. Cecilia’s Convent, Marin Headlands, Walker Art Center, Southern Theater, Red Eye Theater, Bryant Lake Bowl Theater, Center for Contemporary Art Sacramento, Thomas Hunter Project Space at Hunter College, 594 Loft, Fowler Art Collective, and the Flux Factory. She has performed with Emily Gastineau, Emilie Pitoiset, Body Cartography Project, Yanira Castro, Hijack, Morgan Thorson, Karen Sherman, Faye Driscoll, Laurie Van Wieren, Megan Byrne, Anat Shinar, and others. Shogren received a BFA in dance from the University of Minnesota and is always contemplating academia vs. self/socially guided learning as ongoing art piece or practice. She has worked in senior care (PCA, CNA, therapy-based movement) and as a caregivier to individuals with dementia, autism, and developmental delays. In 2010 she received a fellowship for a residency in Skagastrond, Iceland at the Nes Artist Residency. She was voted the 2008 City Pages Dancer of the Year. She was part of the Brooklyn based art collective, Non Solo, whose work has been presented many places around NY, and throughout the West Coast. She has written on performance and art for Mn Artists, Good Job, RELAY RELAY, Thomas Hunter Project Space at Hunter College, InDigest, Critical Correspondence, and NY Arts Magazine.

This article is part of a series of artist responses to the Covid-19 pandemic, edited by Mn Artists Program Manager Emily Gastineau.

[1] Rachel Epp Buller and Charles Reeve, ed. Inappropriate Bodies; Art Design, and Maternity (Bradford, ON: Demeter Press, 2019).

[2] Octavia E. Butler, Kindred (Boston: Beacon Press, 1979).

[3] Isabell Lorey. State of Insecurity; Government of the Precarious (London/New York: Verso, 2012).

[4] Lewis Hyde, Trickster Makes This World (New York: North Point Press, 1998).