Exchange: a conversation on painting with Ute Bertog

mnartists.org continues its series of artist-to-artist conversations, this time with artist Ruben Nusz and German-born, MN painter Ute Bertog, on the relationship between language and painting, the merits of Amy Sillman and the perks of miscommunication.

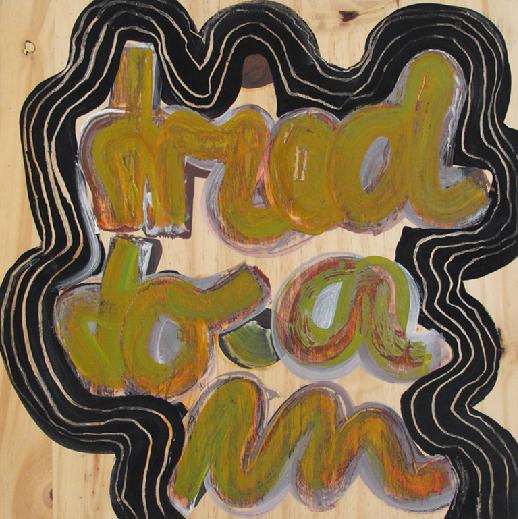

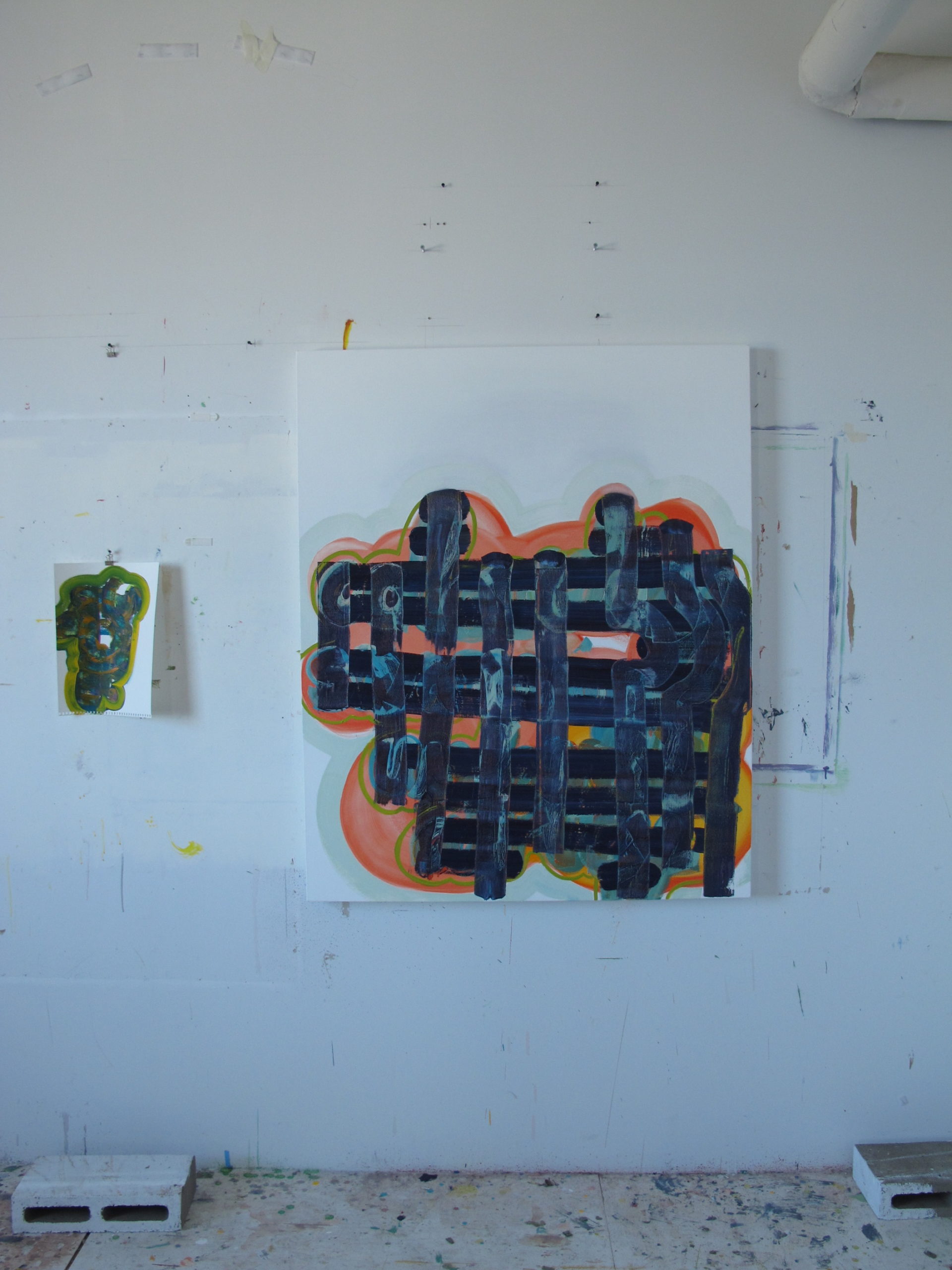

introductionUte Bertog was born in a small town in southwest Germany and resettled in the United States in 1998. Though initially trained in business and economics, this move provided her the impetus to follow a life-long dream of becoming an artist. Infused with hidden texts, her paintings present themselves as a built-up process of working and reworking as a means of muddying lines of communication between the artist and the viewer. The interview below begins mid-conversation with a discussion of Bertog’s recent trip to New York City.

ute bertogNew York was crazy and fun. I saw a lot of art, too much to really think about it in a straight fashion. Lots of galleries in Chelsea were closed for installation, though. Nevertheless, I saw the ones I really wanted to, like the exhibitions of work by Amy Sillman and Wilhelm Sasnal.

ruben nuszThere was a little write-up about the Sillman show in the New York Times. How was the Sasnal show?

ubI have to read that piece on the Sillman exhibition; I loved the show. The Sasnal show left me disappointed, though. It seemed nonchalant, in a way. I’ve never seen any of his paintings in person before, so I have no way of putting the current show in context. But I couldn’t shake a feeling that it was arrogant.

rnHmm — that’s an interesting take. I typically respond positively to Sasnal, but I can see where you’re coming from. In some ways, Sasnal is like a watered-down Tuymans, who is himself watered down Richter. As for Sillman, I’m probably the only painter around who doesn’t really enjoy her work. I saw some paintings of hers in Phoenix, and I find her technique to be provincial.

ubProvincial? How come? As for Sasnal, I actually like all the references in his work to Tuymans and Richter. And, I have to say, I do like Sasnal’s work in reproduction. That’s why I was so curious to see it in person. It makes me wonder if some work is just better in reproduction from the start, as if it were made for it.

rnI actually think Sasnal’s a very clever and crafty painter. I saw some of his work in London a few years ago (the smoking women), and I thought they were cool — in more ways than one (conceptually rigorous, colors were cool in temperature, etc…). Regarding Sillman, I feel that she reveals her references in such an obvious way that there isn’t much new for me to enjoy. Her work just doesn’t look like 21st Century painting to me. I’m a painter, and I love the form, but I want to be surprised. She doesn’t offer me something unexpected the way a lot of other painters do, like Thomas Nozkowski or Richard Aldrich. What about you? What do you respond to in Amy Sillman?

ubI agree with you that I want to be surprised by paintings — and I’m including my own paintings in that regard, by the way. My paintings surprise me that way sometimes; I mean, sometimes they don’t look to me like they’re mine at all. They seem to point to someone else as the painter. Yet, at the same time I have no idea how I think a painting of mine should look — but I digress. What makes me curious about Sillman’s work is the question: Why is it somehow okay for her paintings to look so much like the work from the ’50s, when for so many artists, it’s a taboo? Maybe it is because she uses her references so overtly; those references become a kind of idiom to be used and to be communicated with in her work. On a very basic and personal level, I simply respond esthetically to her paintings; her sense of color is superb. But it’s not just Sillman’s use of color [that stimulates]. It’s also the seemingly endless editing process that I find very interesting; actually, what she appears to be doing comes quite close to my own process. Seeing Sillman’s work makes me want to go into my studio and paint.

rnI agree, there’s an appealing physicality to her painting, rooted in abstract expressionism and Matisse, and that makes it attractive. With regard to your own work, could you provide some background information about your practice? Specifically, how is it that you came to be a painter after earning a master’s degree in business in Germany?

ubI am a person of detours, never going the direct route for some strange reason. In the back of my mind, I’ve always had the desire to be a creative person, yet in Germany it’s not that easy to get into art school, unless you have a long history of art making, which I didn’t have at the time. I had a very talented friend in high school, who could draw like nobody else; that relationship marked me for life — from then on, I had this idea that only the truly talented can be artists. But, an opportunity [for a change] arose when my husband and I decided to move to America. I went in for a complete career overhaul, and I signed up for art classes at a community college, which allowed me to build up my portfolio, and finally got me into MCAD. Now, I don’t want to look back anymore and can’t believe how much time I spent doing something else, something I really didn’t like that much.

rnIn an earlier conversation, you mentioned that your work is, in many ways, about miscommunication. Could you talk about this in more detail, especially given the context of this conversation which, like all conversations, is a breeding ground for miscommunication?

ubMiscommunication is very much wrapped up in my experience as a foreigner. My native language is German, making English my acquired, second language. What speaking in a second language does is suspend all communication in a sphere of uncertainty. That’s not so much the case anymore for me, as I’ve gotten more comfortable communicating in English — but it still sometimes happens that I don’t know the exact meaning of a word, yet I still try to use it. From there emerges the possibility of miscommunication. Though, miscommunication, in my view, is not completely negative, although naturally we associate negativity with it — it’s a failure, after all. We don’t often ask ourselves what might emerge from that failure of conveying directly and to the point what we want to say. Maybe a new insight will be reached, or a fight — who knows? But what’s most important is that, because of the miscommunication, opinions and old thought processes are tested and, hopefully, opened up.

rnIn what ways does painting help you communicate, given the premise that language is, at times, inadequate? Also, when is miscommunication positive?

ubPainting, and especially abstract painting, is the perfect [vehicle], in my view, for talking about this issue of language, and about the fact that it’s not as transparent and direct [a mode of communication] as we might hope it would be. Will painting help us to communicate better? I don’t think so — that would be asking a lot. But painting can help make that opacity of language more apparent, and put some doubt in our belief otherwise.

And when is miscommunication positive? When it helps to open up new questions, and when it forces us to be clearer in our sputterings. Here, I don’t want to imply that painting does a better job than language. That would be rather pompous. But what painting does perfectly — and I am talking here about abstract painting — is that it’s not about communicating clearly at all. In my view, abstract painting has a rather reluctant relationship to language. So, it can communicate miscommunication by doing just that — by failing to convey a clear message.

rnWow — I love that. Painting’s failure of communication, then, has the potential to open up more possibilities for interpretation. I wonder, though, if some abstract painters would argue that abstraction communicates very clearly. A Malevich black circle might be considered attractive because it is, indeed, quite direct and simple — in that sense, it’s possible that abstraction is even more efficient at communicating meaning than language. How would you respond to this?

ubYes, exactly — that is what I am aiming for: to open up the possibilities of interpretation. I am aware that my take on abstract painting might not be in sync with everybody else’s. My counter question for you would be, what is it that Malevich’s black circle communicates, outside of itself? If it’s about that black form floating on a background, you’re right. But if the painting does want to say something else, something bigger than itself — right there the communication becomes murky. I am aware that it is an annoying quirk of mine to always look for the meaning beyond the surface; that might actually be my problem.

rnYou mentioned that you’re “a person of detours.” I love the notion that our lives are amorphous in this way, and you seem to embrace that ambiguity. How does that tendency affect your work?

ubYes, I do embrace it — for better and worse. It affects my work in that I refuse to pre-determine what I do. I approach every painting as if it were my first, which puts a lot of pressure on me; I’m always starting from scratch, in a way. Failure continually seems to be lurking around the corner. But, at the same time, this also keeps me open and my eyes fresh. It helps me to keep dreaming of other things — I am a big dreamer.

rnI totally understand what you’re saying about failure lurking, but that’s what makes the process exciting, isn’t it? What I find the most troublesome about painting, lately, is that I look to it to fulfill a certain need to move beyond failure; it’s like I’m searching for that moment when a painting is newly finished, new to the world for only a few seconds and you’re able to think, for a moment, that it’s perfect. That the world is perfect; that you’re perfect; that everything is … perfect. But, then, that feeling of satisfaction dissolves. I’ve become skeptical of these emotions lately; as my long-term relationship with painting continues, I find this experience still enjoyable but short-lived. Does what I’m saying resonate with you?

ubOh, the excitement of a newly finished painting! We are still romantics at heart, aren’t we? But just like you, I am a skeptic. My mind tends to interject on those feelings of satisfaction pretty quickly, and soon enough, the romance crumbles. On the surface, I try not to chase that feeling, because it’s not really the point of the work. But deep down inside, I too am secretly waiting for the relief it brings. It gets harder to achieve over time, though — maybe it has to do with surprise. The more you do, the less the work you finish succeeds in surprising you. But, once in a while, a piece comes along, and I get a glimmer of that sweetness. And it feels oh, so good.

rnSince life, like painting, is full of detours, where do you see your work going next? How does this conversation end?

ubRight now, I am preparing for a show later this summer; the focused work is very satisfying and is providing clues and pointing towards opportunities in multiple directions. For example, I see the two approaches of my work, the tape paintings and the text paintings, merging or colliding at some point. These approaches are already so closely related, in my process as well as in my understanding of them, that it doesn’t make sense to keep them separate any longer.

How does this conversation end? You know, I am a proponent of open ends, of leaving with a question mark rather than an exclamation point.

About the artist: Ute Bertog graduated from the Minneapolis College of Art and Design in 2005 from the Department of Painting; she received several scholarships and awards during that time. She has exhibited her paintings at Thomas Barry Fine Arts, Sellout Gallery, Altered Esthetics, the DeVos Art Museum in Marquette, MI, the Plains Art Museum in Fargo and the Sioux City Art Center in Iowa. This fall, she will be part of the Greater Minneapolis 2010: A Theory of Values show at the Soap Factory.

About the interviewer: Originally from South Dakota, Minnesota artist RUBEN NUSZ was raised by cowboys and later graduated Summa Cum Laude from the University of Minnesota. In 2003 Nusz directed a feature-length documentary that toured the festival circuit. He has exhibited mixed-media works at the Minnesota Museum of American Art, Rochester Art Center, Art of This Gallery, Umber Studios, the Hopkins Center for the Arts and Concertina Gallery in Chicago. He is also co-founder and editor of Location Books, a quarterly series of limited edition artists’ books highlighting idea-based artworks in all forms of media. Essentially a gallery between two hard covers, Location focuses on unmediated, original, book-form “installations” and curated group exhibitions in print.