Exchange: A Conversation on Painting with Joe Smith

Painters Joe Smith and Ruben Nusz sit down for a far-ranging conversation, about self-help and primal gestures, blankets and childhood, making and seeing things in the unfixed, unnamed moment before language.

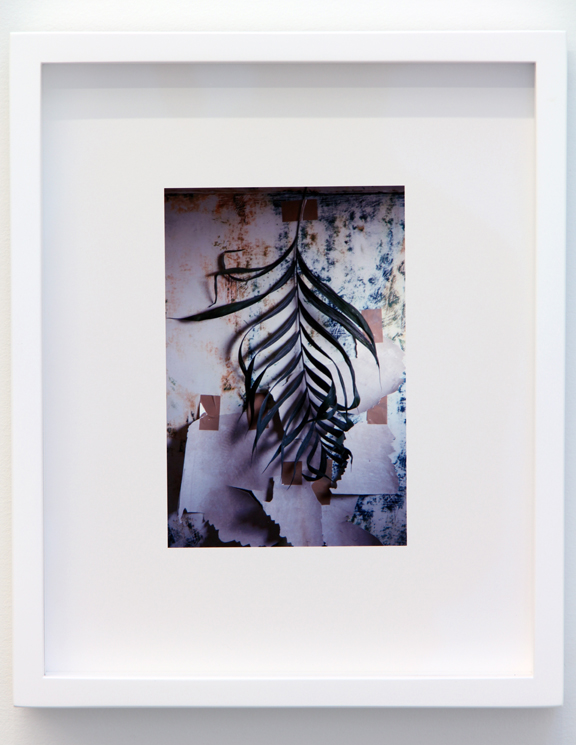

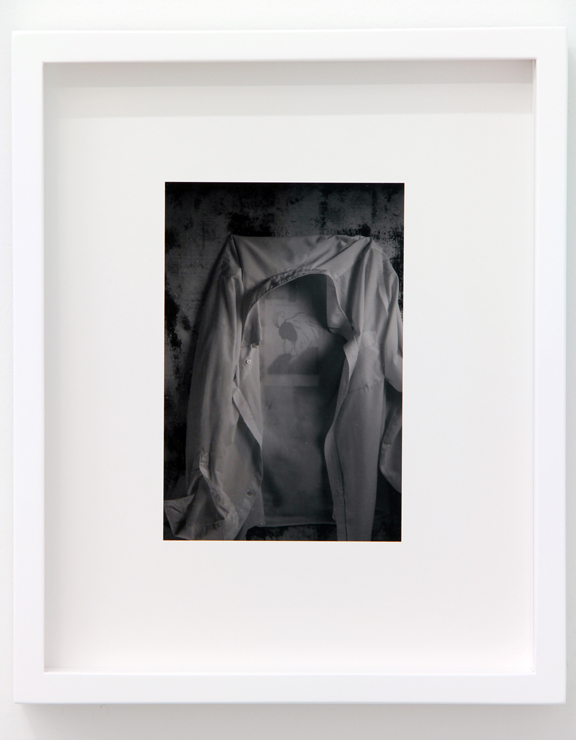

introductionOn a Sunday in March, painter Ruben Nusz sat down with Minneapolis-based multimedia artist Joe Smith to discuss his work and the process of making it, and specifically the new pieces, on view in Smith’s recent exhibition, Softside at David Petersen Gallery in Minneapolis. Their conversation covered a range of issues and ideas including the pre-verbal, wicking, and the flexibility of painting as a medium for contemporary artists.

Ruben NuszBecause of the inclusion and references to baby blankets and self-help books in your show, Softside, I immediately think of psychoanalysis and psychotherapy when I consider your recent work. It makes me curious about your past. What was it like for you growing up? And does this personal history have anything to do with your work now, later in your life?

joe smithWell, I’m adopted. My brother and sister are Korean. There was a divorce in the house. The question of identity was not a tricky one: there it is. I didn’t look to my parents to tell me who I am, and I didn’t spend a great deal of time searching for other truths. It’s liberating in a sense — when I’m making art, I try to be present in the moment and not make too many assumptions about who I am and who others are. I just let it be.

RNOne of the the traits I like about abstraction in painting is that it can present the illusion that context doesn’t exist — even though we know it really does.

jsContext how?

RNFor example: When you approach an expansive Barnett Newman, you can get lost in the painting so that you have the sense of a direct relationship with color. Does this aspect of abstraction appeal to you?

jsDefinitely. If you’re slow enough, most things create a sense of reflexivity in them. We’re living in a state of dealing with “it is what it is,” not some utopian ideal. Look: you make a mess, you clean it up, you make a mess, you clean it up. That’s our perpetual state. As far as abstraction goes: I think it was a beautiful idea. I’m dirtier than that.

RNYou’re speaking in the past tense about it, as if abstraction no longer exists. Wouldn’t you classify some of what’s in your show as abstraction?

jsNo, I think there are moments of abstraction: this thing you’re looking at is there just so that another can be revealed out of its mirage. And the photos aren’t just photos; they’re about surfaces and spaces, like a painting. It’s a question of expectations. You look at a painting or a photograph, and you have expectations because of the forms’ history; same with sculpture. If you can subvert those expectations and push a fresh moment, possibilities open up. Gesture is more interesting than naming. Once you get to the word “abstraction” and you start naming components in a work, you’re left with an equation that isn’t very interesting.

RNI’d like to go back for a minute to psychoanalysis. I’d like to talk about both the Freudian and the common definition of infantilism, the idea that physical and/or psychological traits of childhood are retained well into adulthood.

jsI’m more interested in the gravity that the gesture can hold. The problem with naming a security blanket or self-help book as such is that that naming becomes a catalyst for how you determine everything else. I’m interested in pushing down, tapping into primal experiences. The first painted blanket–there’s a certain pleasure or security that is both received and denied. I’m interested in desire, in what we can and cannot have. I’m interested in the relationship between self and self-control. There’s a certain kind of self-control you don’t have as a child, and that same struggle with impulse control continues into adulthood. This clouds the issue somewhat.

RNWhat is the issue?

jsI’m activating a space, and this space allows for myriad associations and directions. I’m tapping into a slowness that doesn’t seem to happen with naming. Naming gets in the way. Julia Kristeva talks about the pre-verbal, how the pre-verbal is the place in a moment of contemplation where an idea has the most energy.

RNAnd all of your pieces are untitled.

jsMany of the pieces are untitled, yes. Because as soon as I direct your attention, you can’t even look at them as paintings anymore. I’m interested in what painting can and can’t do, what it means to be present in the moment of a thing. This requires that you haven’t named it. When you name something you lose that moment. Once a child names something it’s done.

RNIt’s done, because then you assume you understand it. For me, your work in Softside engenders a certain anxiety. Could you talk about that and maybe about hesitation?

jsI don’t know that it causes me anxiety. I’m really comfortable in that uncomfortable space. [Both laugh]

RNThinking about the surfaces of the blankets, and gesture: could you talk about the primal gesture and what that means in your work? I mean, humans have been making paintings for thousands of years, potentially before language.

jsA primal gesture, to me, is about less filters. I think you’re talking about a couple of issues: impulse and need. I’m interested in both. I want to create a directness in the application; the act [of the gesture] also lends an immediacy to the experience [that’s not predetermined]. I don’t know how things are going to come out. I have impulses that could act as a kind of mediation for the experience, and I try to shirk that as much as possible so the results in the work are less encumbered. So that the objects I make can just be painting, blanket and mental surface — all of those gestures at the same time.

A primal gesture is about less filters. I’m interested in impulse and need, in a sense of immediacy and an undetermined experience. I don’t know how things are going to come out: I want the objects I make to be able just to be painting, blanket and mental surface – all those gestures at the same time.

RNLets talk about that center piece with the metal bar: it hints at a cross. I thought I caught references to Joseph Beuys and the Christ narrative in the history of painting; there’s a crucifix chunk that seems to be coming out of the bucket.

jsThe painting–on one side it’s flesh-colored, and there’s a lot of the body. The “backbone” is a handicap rail. The work props itself up in a pathetic way. Is the spiritual in this work? Sure. Is the psychological in the work? Sure. Is the physical in the work? Sure. I did a show in Chicago titled, Bring Only What You Can Carry; my thought is that you’re going to bring your own issues into the room with you when you see my work. With Softside the same applies.

RN“Bring only what you can carry:” when you mention that, it calls to mind that moment in history of painting, when canvas was introduced in the fifteenth century, which meant you could make bigger pictures and still transport them. What went into selecting the blankets you used? Was their weight in any way a factor?

jsI was interested in two kinds of blankets: ones that were designed and fabricated, a clean space; and then those that had been used by another body, a less clean space. I started by stretching two blankets. They weren’t painted on. And then, I thought: What if I whitewash the next few? When I did, the body, the physicality of them became more present.

RNThis makes sense given the title: Softside. If the pieces were stretched, they’d be too rigid.

jsThe title, “softside,” implies a hard side, too.

RNAnd vulnerability. With any exhibition, an artist puts himself or herself out there.

jsI prefer to live in a vulnerable state. It’s good for us; you risk something. You risk failure. Without that, there is no self-understanding, no understanding of potentiality.

RNAnd the sculptures?

js[Making the sculptures] I thought about consumption, and about preserving. The sculptures needed to be salt– colored salt. The seal pulls down as the wicking pulls up.

RNThe same leads into painting as well, like Helen Frankenthaler. Your blankets, too, have references to color field painting.

jsAnd action painting as well. If Morris Louis pours and stains, what does it mean to ‘wick?’ What does it mean to absorb and suck? Two of the blankets have paint that’s been forced through, like a mass of will pushing through the fabric. That seems to me more interesting than splattering. There’s also saturation. [The blankets] are able to contain the history within which they’re working and at the same time deny that history. I want to turn things on their head, so that you don’t know where you stand, so you must think. Once you label something, you assign meaning and then don’t have to think about it; you just consume it, and that is empty. What if we slow everything down instead? That could cause frustration and irritation. Or liberation.

RNOr the blank slate, a kind of vertigo. … What about the self-help books in your work?

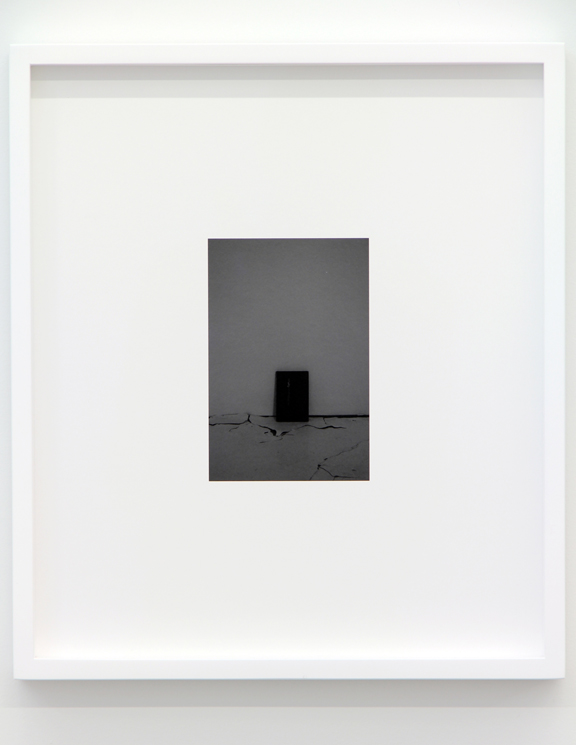

jsI wasn’t interested so much in the content of the books themselves as I was in the space those sorts of books articulate: some gap, an undetermined need.

RNThat idea echoes the ways that American abstract expressionists wanted to help themselves: to isolate themselves from Europe, create something American that spoke to American individualism, etc…

jsThe first self-help book was not about self-help at all. The first one, [published in 1859, was Self-Help] by Samuel Smiles and it basically talked about all the ways one is capable. He insisted that we are all ultimately capable, that we can all achieve a place of equanimity where we’re fine. If you want to improve, you’re capable of that, too, but there were no tips in his book — not one. Contemporary self-help books are more like lists of corrections or DIY manuals. I started asking people for their self-help books. This turned out to be a really personal question, like I was asking to look in their underwear drawer. Our issues are personal. You start seeing these books on the shelf and you choose; you start to choose your issues. I became interested in how reflexive this material is, like a painting but more specific.

In my work, it’s about what the combination of these books with the cracked floor in my studio does, what emotional and psychological space is evoked, and how that is amplified by a white-washed blanket and a salt soaked pillar. I can’t take on people’s health, let alone my own. It’s more like: I AM. As long as I stay there, it makes me aware. It makes me now.

Noted exhibition details: Softside: Joe Smith, is on view at David Petersen Gallery in Minneapolis through March 16, 2013, when the gallery will host a happy hour closing party for the show at from 4 to 6 p.m.

JOE SMITH (b. 1970) received his MFA from Cranbrook Academy of Art in 1998 and has been the recipient of several grants and fellowships, including The McKnight Fellowship for Visual Artists, the Minnesota State Arts Board Artist Initiative Grant, and The Jerome Travel Grant. He has exhibited in numerous venues, including Midway Contemporary Art, Occasional Art, and The Soap Factory in the Twin Cities, and The Suburban and Julius Caesar in Chicago. He currently lives and works in Minneapolis.

Born in 1978 in South Dakota, Minneapolis/Saint Paul-based artist RUBEN NUSZ graduated Summa Cum Laude from the University of Minnesota in 2001. He has exhibited work at the Walker Art Center, The Minnesota Museum of American Art, The Rochester Art Center, The Soap Factory, the Kiehl Gallery at Saint Cloud State University, and Weinstein Gallery in Minneapolis. His work is featured in several private collections as well as the permanent, public collection of the Minnesota Museum of American Art, The Weisman Art Museum and the North Dakota Museum of Art; the Walker Art Center Library owns one of his artist’s books. In addition, he’s a contributing arts writer to the website mnartists.org. Nusz is also co-founder of Location Books, an independent publisher that provides contemporary artists the opportunity to produce new work in book form. Location is featured in the libraries throughout the United States, including the collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Museum of Modern Art.