Conversations on Improvisation: George Cartwright

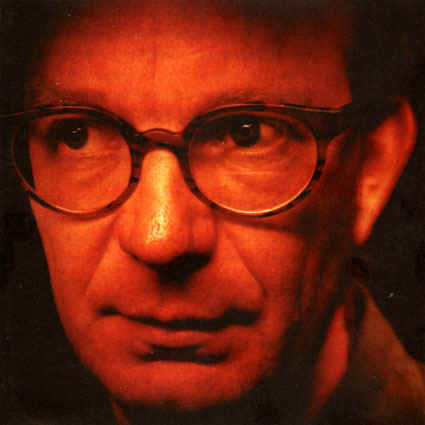

Pamela Espeland's interview series on the nature and practice of musical improvisation continues with acclaimed saxophonist/composer George Cartwright (of Curlew, Gloryland Ponycat, and others).

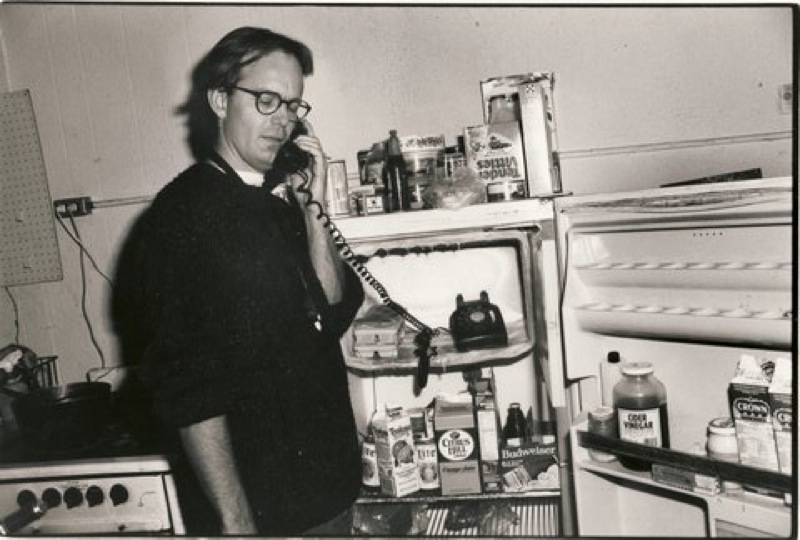

IF YOU TALK ABOUT GEORGE CARTWRIGHT WITH AN IMPROVISING MUSICIAN from out of town, that person will invariably say, “George Cartwright lives in Minnesota?” Known for holding down the Knitting Factory in New York with his group Curlew in the 1980s and 1990s, saxophonist/composer Cartwright is an improvising monster in our midst. In a recent interview for All About Jazz, Gordon Marshall called him “part of the archaeology of modern New York.”

When I first wrote about Cartwright in 2007, I was too intimidated to interview him live, so we talked via email. Since then, I’ve seen him perform and have spoken with him several times. I’ve learned that he’s a Southern gentleman and a scholar, an avid reader of Charles Dickens, and a man who adores his wife, artist Anne Elias, and their young son, Ray. He doesn’t go out much or play out as often as he could, because he would rather spend his evenings at home with them.

Born in the Mississipi Delta in a town called Midnight, Cartwright grew up on rock-and-roll and fell in love with jazz after hearing Charles Lloyd’s iconic Forest Flower album. He earned his B.A. at Mississippi State University and then briefly attended Jackson State, Memphis State, and the University of Southern Mississippi before deciding that he’d like to study with multi-reedist/composer Anthony Braxton. (In 1994 Braxton was awarded a MacArthur “Genius” grant.) Cartwright saw an ad in DownBeat magazine for something called the Creative Music Studio in Woodstock, New York, founded in 1971 by Karl Berger, Ingrid Sertso, and Ornette Coleman. Its rotating faculty included people like Braxton, Oliver Lake, Dave Holland, and Wadada Leo Smith. “It seemed like a good idea,” Cartwright recalls. “It turned out to be fantastic. You’d hang out with those people, eat with them, practice their music with them, and perform it. They would treat you like you could play their music.”

From Woodstock, Cartwright moved to New York City and formed Curlew, which has variously been described as “protean,” “obstinately committed,” “the best live band in the USA,” and “the seminal New York squirrely downtown jazz ensemble.” He learned to be a decorative painter (doing custom work like glazing, graining, marbling, and gilding) so he would never have to take a music job he didn’t want.

Since moving to Minnesota in 1999, Cartwright has recorded with his band GloryLand PonyCat, been named “Best Jazz Artist of the Year” by City Pages (2004), won a McKnight Composer’s Fellowship, and received a Jerome Foundation grant to write the score for a radio play by Curlew member Davey Williams, called Bonanza: The Musical. (Read my review of the show here.) He’s currently working with a new band, as yet unnamed, with Adam Linz, Alden Ikeda, Andrew Broder, and Paul Metzger.

Cartwright asked that I share a quote from Williams: “Music is like rain. Except music falls up.”

________________________________________________________

Pamela Espeland: When I talk with improvising musicians from other parts of the country, they’re surprised to learn that you live here instead of in New York City. How long were you there?

George Cartwright: Fourteen years.

PLE: What brought you to Minneapolis?

GC: My wife’s family is from here.

PLE: Have you found what you want and need here as a musician?

GC: The music scene here is unbelievable. When I moved here, I thought, “The family’s here, the schools are good, Ray will like it, and I’ll go back to Memphis and New York for a gig every once in a while.” I didn’t really have any expectations. Then Alden Ikeda called me and said, “Man, I heard you moved here! I’d love to play with you!” He was so nice to me, and I started playing with him, and then I met Carei Thomas and Adam Linz and Andrew Broder and all these other people who are really, really good. If I had time, I could play more here than I ever played anywhere.

PLE: You’ve said that you have always eschewed journeymen positions in music so you could compose and perform your own music, free from traditional constraints. How has that worked for you?

GC: Fine. I never wanted to play in a pit orchestra or a big band. If someone called me, I’d think about it; but nobody’s gonna call me. I’m very happy with that. That’s why I try to make money a different way. If I was going to play music, I was going to do it like I wanted to do it.

I have this idea of music, this romanticized version, that it’s a kind of magic. Musicians, especially jazz musicians, are supposed to learn things by ear, learn about the music so they can re-create it. I never did that much, but the few times I did, I was so disappointed. I thought, “Oh, those are the notes? Where’s the magic?”

PLE: In an interview for All About Jazz, you told Gordon Marshall, “I don’t want to play what I hear, I want to play what I can find!” You’ve also said that you started finding melodies after hearing Ornette Coleman’s Dancing in Your Head. What do you mean by “finding” music?

GC: You just play, and you look for it. In improvised music, you’re finding the music as you go along at that moment, figuring it out while it’s happening. It has a mind of its own, to a certain extent. You’re trying to follow where that is and push a little bit or lead a little bit, lay back or lay out; you make it as you go along. Making music is like finding it. We only know about it in hindsight: “We found that tonight.”

I have a theory that, when you improvise, there’s the perfect music you could play that night — it would just be perfect for that time, space, people, audience, and in history. There’s a perfect piece of music there for you to delineate somehow, and you need to find it. You start responding to it and find some more.

PLE: You also compose music. So, there’s a certain expectation that, at some point, people will play what you’ve written. Do you want them to play your music as you’ve written it, play it in their own way, or both?

GC: Both. I like to write stuff that people will play and change, so that it becomes something quite different. I was rehearsing with Andrew Broder a while back, and he said, “Can I add a little distortion to this?” and I said, “Oh, please do.” It’s about enabling people who are kind enough to play my music, and they enable my music to be better by finding their own way into it.

PLE: When did you first become interested in improvisation?

GC: Probably as a teenager, playing the guitar. I really liked John Fahey. I liked making stuff up.

PLE: Did you consider what you were doing composing or improvising?

GC: Just messing around. I don’t know when I first heard the word “improvise.”

PLE: How would you define “improvisation”?

GC: I would say it was somebody who was trying to make the very best music they can at that moment.

PLE: Solo or group?

GC: I was thinking solo, but in a group it’s the same thing. You’re trying to make the best possible music you can. Usually, people know each other, or they’ve heard each other play. There’s a filter of some kind to get you together. You want what they do, who they are, how they play. And then when you start improvising, you use all the little musical tools you have; you make choices. You listen, or you don’t listen. You play, or you don’t play. You play loud, soft, fast, slow. You try to play with the other people; you try not to play with them, but counter to them. Things like that. It’s as if you and I were going to have a conversation, and we want our conversation to mean something, but we have to talk at the same time and speak in languages that no one else can understand.

Wadada Leo Smith once said, “Your job is to not be so absorbed in the music that you don’t know what’s going on.” You have to hold back a little so you can make decisions and choices about how you’re going to execute the next notes you play. You have a responsibility to the audience to make the best music you can.

PLE: Does the audience have a responsibility?

GC: No — but I think the audience should have a desire. Speaking for myself, I have a desire to hear music; I hope it’s fantastic, that it will change my life. That’s what I like about music. That’s what I want. The audience should do whatever they want. Hopefully, they’ll hear the music and go, “Wow, what in the world was that? I don’t know what that was, but I really liked it.”

PLE: What goes on in your head when you’re improvising?

GC: I’m always thinking. The first thing you have to get out of the way is starting. When [drummer] Davu [Seru] and I play, he might start, I might start, or we might start together — it just depends. But that kind of sets a tone, and then I will choose to go that way with him; or, maybe I’ll go in a different direction, or try and get inside what he’s doing. I might watch him out of the corner of my eye, and when he hits something, I might play a note. I might close my eyes and just listen. I might find some path to go down for a while and play along that in a certain manner, and get to the end of it, kind of, and then decide to stop or keep going. A big part of improvising is waiting: sometimes you wait until you know that it’s time to play again, or you wait to not play.

PLE: How do you know when it’s working?

GC: You don’t know until it’s over. You can get done and [in the moment] think, “Great gig!” and then, you listen to a tape and think, “I’m not so sure about that.” Or, you can think it was awful and then hear a tape and go, “Oh!” So, you try not to judge. I try to keep it all up in the air.

PLE: Does time speed up or slow down while you’re playing?

GC: I think it slows down. There have been many times when I thought, “I played for a really long time,” and then I listen and it’s been a very short period.

PLE: Kind of like a car crash.

GC (laughs): Well…maybe there’s another way to put it. But the time thing is weird, because it changes. You’re executing little, bitty, precise things pretty fast.

PLE: Charles Mingus once said, “You can’t improvise on nothing.” Do you have a starting point?

GC: Always.

PLE: What is it?

GC: It’s just the first little bit you play.

PLE: Do you plan that out ahead?

GC: Although it makes me very anxious not to know, I prefer not to know ahead of time. I prefer to get out there and just start. Sometimes, if I’m especially nervous, I’ll calm myself by coming up with a way to start. But then, usually, when I actually start to play, I’ll end up doing something different.

PLE: You recently made a new record with Davu called Rag. Did you play music you had written?

GC: No.

PLE: Did you talk ahead of time about what you were going to play?

GC: No.

PLE: So, you just showed up, started playing, and recorded whatever happened?

GC: Yeah. (Laughs.) Sad to say.

PLE: Is there anything people can do to prepare to hear you play?

GC: No. They just need to show up and like it or not like it. If you don’t like, it, you can leave.

PLE: A lot of people think they have to understand jazz before they’re willing to try it.

GC: I don’t understand jazz. What’s the problem?

________________________________________________________

Watch an excerpt from “The Hardwood: Curlew Live at the Knitting Factory” (1991) from the Cuneiform re-release A Beautiful Western Saddle (2010).

Watch the last eight minutes of Bonanza: The Musical, filmed live at Studio Z in St. Paul, MN, January 23, 2010.

________________________________________________________

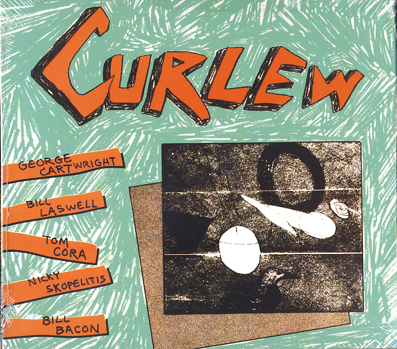

Discography:

George Cartwright and Davu Seru, Rag (Roaratorio, 2010). Limited edition of 300 LPs, each with original art by Anne Elias.

Curlew, A Beautiful Western Saddle (Cuneiform, 2010). CD/DVD. A reissue of long out-of-print recordings plus previously unreleased material and vintage live video. With (in alpha order) Samm Bennett, Pippin Barnett, Rick Brown, George Cartwright, Fred Chalenor, Chris Cochrane, Tom Cora, Amy Denio, Anton Fier, Fred Frith, Bruce Golden, Dean Granros, Wayne Horvitz, Mark Howell, Chris Parker, Ann Rupal, Nicky Skopelitis, Davey Williams, Otto Williams, and Kenny Wolleson.

George Cartwright, Send Help (Innova, 2008). With Adam Linz, Alden Ikeda, and Andrew Broder.

Curlew (DMG/ARC, 2008). A re-issue of the very first (self-titled) Curlew LP (1981), plus bonus material. With George Cartwright, Tom Cora, Nicky Skopelitis, Bill Laswell, Bill Bacon, and Denardo Coleman.

George Cartwright, A Tenacious Slew (Innova, 2007). With Adam Linz, Alden Ikeda, Anne Elias, Chris Parker, Christine Baldwin, and JT Bates.

George Cartwright, The Ghostly Bee (Innova, 2006). With Davey Williams, Bruce Golden, Adam Linz, and Chris Parker.

George Cartwright’s GloryLand PonyCat, Black Ants Crawling (Innova, 2003). With Adam Linz and Alden Ikeda.

Curlew, Gussie (Roaratorio, 2003). Limited edition of 436 LPs, each with original art by Anne Elias.

Curlew, Meet the Curlews (Cuneiform, 2003). With Davey Williams, Fred Chalenor, Bruce Golden, and Chris Parker.

George Cartwright, The Memphis Years (Cuneiform, 2000). With lyrics by Paul Haines.

Find even more here (search Cartwright and Curlew) and here (search Cartwright).

________________________________________________________

About the author: Pamela Espeland writes about jazz at Bebopified and keeps a Twin Cities live jazz calendar. On most Friday mornings at 8:30, she previews upcoming jazz events on “The Morning Show with Ed Jones” on KBEM radio.