Brave Words

Connie Wanek urges you to read Lucille Broderson's debut book of poems, But You're Wearing a Blue Shirt the Color of the Sky (Nodin Press, 2010), calling the 94-year-old poet's work a thrilling achievement, bold, direct and moving from beginning to end.

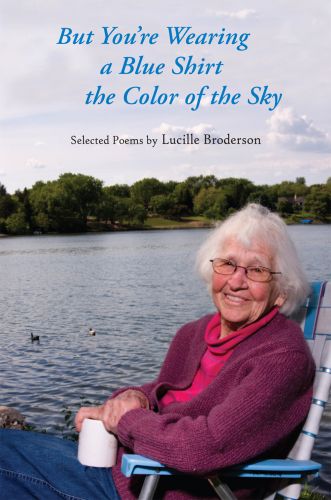

IT’S AN INTRIGUING TITLE FOR A BOOK OF POEMS: But You’re Wearing a Blue Shirt the Color of the Sky. The front cover features a photograph of the author, 94-year old Lucille Broderson, smiling, posed unpretentiously in a lightweight aluminum lawn chair, her left hand steadying a coffee cup against her crossed leg. In the background, two ducks drift on a Minnesota lake. It’s a placid summer day. This is a forthright, thoroughly Minnesotan image, calm and friendly. Nothing about the cover quite prepares the reader for the psychological depth and emotional pitch of many of the poems within.

The initial poem, “Eight of Us,” provides the first hint of what this book will accomplish. This poem covers about eighty years in thirty lines, providing a summary of the lives (and deaths) of seven siblings. Already we’re struck by the honesty of the approach, the way simple words can penetrate; figurative language is kept to a minimum. The brothers and sisters “sagged/in their chairs, afghans on their knees,/eyes huge behind thick lenses.” Broderson says, “Now I’m the last,/of all those faces around the table,/all those bodies warm in bed.”

There’s not much point in pondering whether the speaker, the “I” of the poem, is or is meant to be Lucille Broderson herself. After all, her photo is right on the cover and seems to announce, “Here I am.” What matters is what has always mattered in literature: Are the poems effective, and affecting? Yes, absolutely. They are brave and vivid, some of them so searing that we’re left stricken by their power.

And where does that intriguing title come from? It’s the last line in a poem called “Requiem,” reprinted below in full:

The children tiptoe past my sleeping room,

past the chair I drowse in.

The days go like April’s daffodils

and now the asters wither, too,

and I haven’t even seen them.

I wait for the sound

of bluebells ringing.

An old pumphandle creaks,

water splashes,

tastes iron and runs cool on bare feet.

You move among the tall grasses,

wave a white handkerchief across the field.

I dreamed I’d see you in your old maroon sweater

but you’re wearing a blue shirt

the color of the sky.

What makes this poem so moving and alive? Partly it’s the use of details that appeal to the senses, the water that “tastes iron and runs cool on bare feet,” and the white handkerchief, a signal for surrender, a bid for attention. Further, it’s a swiftly-drawn portrait of a soul in mourning, sleeping at odd times, half-aware of time passing, half-knowing what is real. “I dreamed I’d see you in your old maroon sweater/but…” Broderson doesn’t say, you were wearing, but you are wearing that blue shirt. She is looking at the ghost in the present tense, right there in the poem, and it gives her lines heartbreaking immediacy.

Here Broderson recalls Whitman in Song of Myself, as time flexes, and months and moments collapse. She has some of his confidence, too, his boldness. (Now this is a confident title: “Winter, and You and I and the Universe”.) Consider the following lines from the poem “Our Ancestors Want Us to be Happy, Her Son Said.”

“Let me hold you again,” he said.

“Tell me–what do you think of death?”

“I think death is beautiful,” and then quickly,

“Now where did that come from?” and she laughed.

We think of Frost, how he constructed some poems entirely of dialogue, but these lines from Whitman’s Leaves of Grass also leap to mind: “Has anyone supposed it lucky to be born?/ I hasten to inform him or her that it is just as lucky to die, and I know it.”

NOT EVERY POEM IN THE BOOK is about the sorrows one encounters as one ages. Still, this is the work of a woman who has been paying close attention to life over many years. I can’t think of a more compelling story than the one behind this book: Lucille Broderson began writing and publishing poetry in her sixties, and now, at the age of 94, she has assembled a collection that Patricia Hampl calls, without exaggeration, a “magnificent achievement.” Below, in full, is a poem by Broderson that fulfills Emily Dickinson’s famous description: “If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry.”

Letter Never Sent

This letter is about me, the real me, the mother

you’ve never met. The one you invite to dinner

on Christmas or Easter is an impostor.

Or perhaps you already know.

But you’ll act surprised

and hug me hard when next we meet. “Oh, no,”

you’ll say. “You’re not like that.”

I did not have a father, that’s true. He died.

“Oh, how she loved him, how she misses him!”

But I never missed him. I found another…

in the Elsie Dinsmore book.

He meant business, that father.

No! No! Do this! Do that.

And I did it all. Right. How pleased Mother was.

A child that is no trouble.

I grew up not pretty but pretty enough

and a young man wanted me.

He was as good a father as the book father.

He found the house, paid the bills, ordered the children,

loved me, he said, but I never believed.

He died. Too soon, of course, but he left me

“well enough off”: my home, my car, my bankbook.

But I never loved him. Nor the man who followed him.

Then I woke and knew I hated the world,

the people in it, the books that stood every which way

on my shelves, the pages I’d written,

the flowers on the table,

the wide snow-covered lake.

I never loved anything or anyone

but you, my children. Forgive me. It’s true.

This poem is thrilling. I accept that the searing “truth” of this poem is in question, that the narrator may be unreliable, despite the insistence of the last line — it is, after all, a “letter never sent.” But why was it not sent? Because it describes a particular time when even loved things — husbands, books, one’s writing, flowers, the lake — turn dark and unprofitable. “‘Tis an unweeded garden that grows to seed; things rank and gross in nature possess it merely.” (Hamlet) But a mother tries to spare her family her darkest thoughts. One truth the poem does tell us is that the love for our children endures, even when all else is despair. This poem is like a lightning strike.

Michael Dennis Browne, the marvelous poet and teacher, wrote a foreward for this book which is not to be missed. His admiration for the poet becomes ours, too: Broderson’s are brave words, daring and direct. Seldom do I encounter poems that move me as hers do. Her mind is “a beehive…buzzing, working, moving. In and out,/above and below, never, never stopping.”

Related information: Lucille Broderson’s newly released book of poems, But You’re Wearing a Blue Shirt the Color of Sky, was published by Nodin Press in October 2010. She is also of two poetry chapbooks, A Thousand Years and Beware.

About the author: Connie Wanek is the author, most recently, of On Speaking Terms (Copper Canyon Press, 2010). Her work has appeared in Poetry, The Atlantic Monthly, The Virginia Quarterly Review, Narrative, Poetry East, and many other publications and anthologies. She has been awarded several prizes, including the Jane Kenyon Poetry Prize and the Willow Poetry Prize, and she was named the 2009 George Morrison Artist of the Year. Poet Laureate Ted Kooser named her a 2006 Witter Bynner Fellow of the Library of Congress. Her poem, “Polygamy,” was the grand prize winner in the 2010 What Light competition.