Beyond DIY to Do-It-Together

Regan Smith (PAPER DARTS) offers a personal accounting of a trend she's noticed among Minnesota artists - a shifting focus away from strictly individual accomplishment, or DIY ethos, in favor of collaborative, interactive, "do-it-together" creative work.

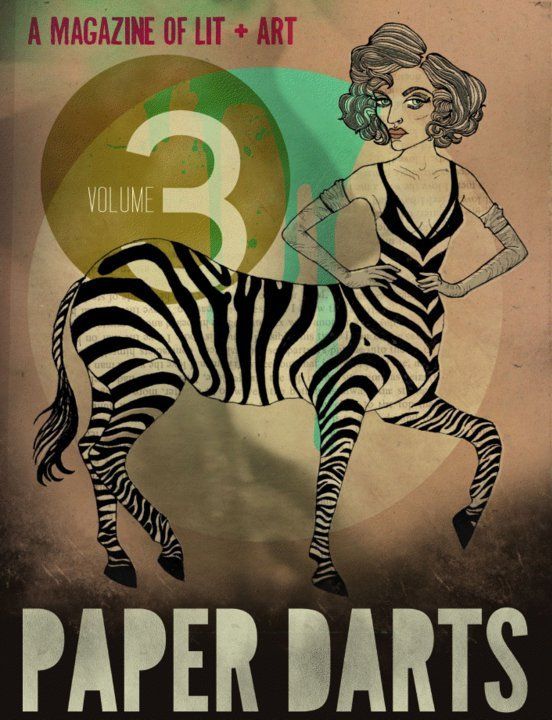

When the three of us decided to start a literary magazine after graduating from the University of Minnesota in May of 2009 — with no jobs, no prospects, and no clue how to turn our respective English, Art, and Art History degrees into anything useful — it was a concept born of passion, and maybe a little desperation, too. Like a lot of people launching a creative start-up, my friends and I had colossal ideas and monumental visions, but no clear plans for how to realize them.

Despite our grand ambitions and relative naiveté, we did embark on this venture with a few key, invaluable principles from the get-go. First, if we were going to avoid the seemingly inevitable crash and burn of so many similarly inspired creative projects, we knew we’d have to offer something different, something more than the norm in our genre. Second, early on we embraced the idea that what we were set on doing likely wouldn’t make us a cent. And third, we made peace with the fact that, for this to work, we’d need to rely very, very hard on the kindness of strangers – and on family and friends, as well as just about anyone else who would give our harebrained schemes the time of day.

It’s now been nearly two years since we launched Paper Darts, and though we haven’t quite realized the full scope of our vision, we’re well on our way: we can currently claim roughly 15,000 unique visitors to our site monthly, we’ve published three print issues, and celebrated each one with launch parties which drew around 100-300 people each; we’re currently working with a highly respected local author and 17 local and international artists on the publication of a short story collection. In a difficult literary climate, where simply hanging on for two years is an admirable accomplishment, our beloved little magazine has persevered, and seems to be on track to tangible success (though we still cringe if pressed into actually saying, or writing such a thing).

While we aimed for our lit mag to be something entirely new, these foundational principles certainly aren’t. Unless you’re incredibly headstrong, willfully ignorant, have a fiscal sponsor with deep pockets and loose fingers, or some combination of all three, most people launching into long-term creative projects usually approach them in a similarly pragmatic way. But that’s no guarantee of success, of course. Hoping for the best but preparing for the worst has always been a mantra for those working in the arts – never more so than now, in this post-recession economic climate, where it seems like every month some new creative industry is declared “dead” or “in crisis.”

So, why has Paper Darts, along with so many of the other collaborative creative projects that sprang up around the same time, been able to buck the odds and thrive? As much as I would like to chalk it up to sheer talent and drive, over the past several months I have come to realize that a very large portion of our success must be attributed to the city in which these projects were born and nurtured.

No matter its merit, Paper Darts, at least, would likely be eaten alive in New York, San Francisco, Austin, or any number of other creative hotbeds in the US. It’s the very nature of the artistic community in the Twin Cities, Minneapolis in particular, that has allowed independent, multidisciplinary artist collaborations like ours to flourish in ways that (laudable principles or not) simply would not be possible elsewhere.

To avoid the creative crash and burn, offer something different

To say that the way content is created and shared has changed drastically in the past decade is not exactly revelatory. We all know that technology has paved over the gap between consumer and producer, and that social media has cultivated a generation of DIY self-promoters, where everyone and their mother (and grandmother and pet hamster) owns Tumblr and Twitter feeds, not to mention a YouTube channel.

Arguing that “embracing technology” and “utilizing social media” are what sets your creative project apart from the rest is no longer even relevant. Been there, done that, and speaking as a representative of my so-called short-attention-span generation, I reserve the right to look down on any journalist or media outlet still hung up on the “Facebook revolution.”

While the way art is produced and consumed today is nothing new any more, the way that creativity has come to be collectively experienced is. The days of isolationism — where an artist produces a piece, hangs it in a gallery, and disappears to leave the public to look at it — are over. Don’t get me wrong: we still love our art, but we love having a good time, too. And the Minneapolis arts community has embraced the idea that the two don’t have to be mutually exclusive. Sure, if a friend or artist I respect is having an opening at a gallery, I’m still happy to head over and check out their work; but if I can do that with a live band playing in the background, a group of people creating impromptu paintings in the middle of the room, and, most importantly, a beer in my hand, so much the better.

Local artist, writer, producer, and all-around creative-savant Andy Sturdevant has mastered this balancing act more than almost anyone else in the Twin Cities. Recently described in an MPR profile as “a one man arts scene,” Sturdevant is intimately involved in an impressive slew of genre-blurring projects, from the Common Room in the Soap Factory to the recent Mississippi Megalops project at the Northern Spark festival.

Salon Saloon, a “live-action arts magazine” Sturdevant co-created with Works Progress and which he hosts monthly at Bryant-Lake Bowl, is a perfect example of the art/party combo Twin Citians have enthusiastically participated in over the past few years. “Salon Saloon worked initially because it was an opportunity for artists to meet at a bar and talk to each other. That’s what we heard over and over from the people that showed up anyway,” he said. “Certainly using social media has made it possible to promote the show without going through traditional media channels. But for us, it came down to the hard-to-deny fact that people just like hanging out. If any art should happen to come out of that… great.”

The way art is produced and consumed today is nothing new any more; but the way that creativity has come to be collectively experienced is.

Big enough to offer a rich, diverse, and abundant arts scene, but small enough to keep over-saturation at bay, Minneapolis/St. Paul provides the perfect culture for these kinds of events to thrive. It’s easier for projects like Paper Darts and Salon Saloon to stand out here in a way they never could in a more densely populated city, or where the public was less passionate about its arts.

It’s not the money, honey

According to the cliché, art has never really been “about the money,” but the assumption that you won’t make a dime off your creative endeavors has never been more widely (if still a bit grudgingly) accepted than it is now. You can make art as much as you want, but you’re extraordinarily lucky if you can also make art that makes the rent, and every modern creative knows it.

Chris Cloud, the Executive Creative Director and mad-genius behind multidisciplinary online video site MPLS.TV, understands firsthand the tensions inherent in that fact – the real necessity of having a day job versus the equally compelling desire to satisfy a creative passion. “I think the recession has made people more resourceful, and has also showed some pretty big flaws in the modern creative production cycle. Production costs have dropped way down as the consumer has evolved into the producer, and with more “producers” out there it’s harder to charge as much for that creative product. However, talent is still around, more so now than ever, so if you make amazing, remarkable art, people will notice,” he said. “Don’t get me wrong: We’d love for someone to come along with a huge paycheck for what we’re doing at MPLS.TV, but we do what we do out of passion for the city and the community. And I think a lot of the creative projects around town are doing what they do for the same reason.”

Although it’s generally difficult to find a full-time “career job” in the arts pretty much anywhere in the country, I have a feeling it’s especially difficult in Minneapolis. As rich as our arts scene may be, the city is still relatively small, and opportunities for full-time work in arts-related organizations don’t open up often. When people do land those jobs, they tend to cling to them for a long, long time.

Despite this lack of traditional career pathways in the arts, however, many Twin Cities residents are still finding ways to piece together a life in their desired creative field. Because of Minnesota’s impressive fiscal support of the arts, opportunities for paying side-gigs and freelance projects are plentiful; and I challenge you to find a city with more enriching arts internship programs. Many people, myself included, have found a way to carve out a lifestyle that may not be the most financially dependable, but which allows us to make a little money off work we’re passionate about, while paying our bigger bills with work that we, well, aren’t. Minneapolis is an ideal place to slowly nurture a portfolio, make a little cash here and there, and figure it out as you go. And it’s this accessibility, this cocktail of cultural employment options, that makes it possible for so many new creative projects and organizations to spring up and thrive as they have — and this proliferation of start-ups has itself added to the variety of practical skills and experience that many artists here now possess.

The kindness of strangers

I’ve heard the term “creative collective” used to describe many of the hodge-podge arts projects in Minneapolis, like MPLS.TV. But Chris Cloud has taken the notion of the collective one step further, unofficially coining the phrase “Do-It-Together,” to explain the approach they take towards the arts community. “DIY is so 20th century,” he quipped. “Nothing against people who’re all about DIY, but why work alone when you can work together, sharing resources, ideas, and thoughts? Most projects and concepts that come from MPLS.TV touch multiple hands or have different people contributing different skills. The best part about doing it together is the shared sense of accomplishment when a project reaches the public.”

“DIY is so 20th century. Why work alone when you can work together, sharing resources, ideas, and thoughts? The best part about doing it together is the shared sense of accomplishment when a project reaches the public.”

While both Cloud and Sturdevant agree that multidisciplinary Do-It-Together projects are on the rise, they’re also quick to note that this collaborative approach to art is nothing new. Artists and thinkers have always worked in groups, and the recent surge of projects springing up in the Twin Cities is not so much a revolution, as it is “the cresting of a wave of complex forces and ways of reasoning that have been slowly building for a long time,” Sturdevant said. Though these collaborative efforts aren’t new or unprecedented, their popularity and support in the community around them in recent years certainly is. Nearly every creative person I’ve talked to about the subject (especially those who aren’t Minnesota natives or who have done long stints working elsewhere) makes a point to mention the incredible sense of peer support and encouragement they’ve noticed in the Twin Cities arts scene. No one is denying that a certain amount of competition (for audience, patronage, critical attention, grant money) still exists among artists here. But rather than the adversarial, kill-or-be-killed attitude you might find in bigger cities with more crowded, less supportive arts scenes, here that drive serves as a curatorial nudge, motivating our creative crowd to think bigger, do better, and, most importantly, utilize the talents of as many other people as possible.

“I think often to a quote I read from a visiting Chicago writer in the 1980s, that described the Twin Cities art scene as ‘a peculiar blend of Scandinavian modesty, social conscience, and an absolute belief in the power of collective action.’ I don’t totally buy that ‘Scandinavian modesty’ bit, but on the whole it generally still rings true. People work very hard here. And while they can be as petty and provincial and judgmental as people can be anywhere, I really do feel on some fundamental level people are interested in working together on multidisciplinary projects. On the whole it seems like the arts community is a supportive, competitive, and collaborative environment,” Sturdevant noted.

And it is precisely the type of environment that has allowed Paper Darts to not only survive, but to continuously grow, evolve, and mature these past couple of years. While the number of literary magazine contenders in the Twin Cities is admittedly small these days, we have yet to encounter a single person we’ve approached who has been anything other than 100% supportive, encouraging, and excited to go above and beyond to help our little organization. Likewise, in my personal experience, I have been amazed at how consistently open and willing other local writers are about sharing their knowledge, resources, and contacts with me as I attempt to carve a career path through the freelance jungle.

Is it possible that there are other cities in the country with Do-It-Together attitudes just as strong as you’ll find here? Sure. But the recent spate of national recognition for our town — naming Minneapolis the most gay-, bike-, or family-friendly city, the healthiest, most literate… and so on — just calls attention to the open secret we lucky Twin Cities residents have been privy to all along. Maybe our collectivist spirit comes from an underdog determination — a sort of Midwestern, flyover country sense of solidarity; or, maybe there is more truth to the Minnesota Nice cliché than we’d like to admit.

Whatever the reason, this fact is clearer now more than ever: There is something exceptional about Minneapolis and St Paul, something that keeps natives here and draws outsiders in. The pull of this place is such that no matter where we might travel on our creative and professional paths, in the end, we will eventually, inevitably, and in some ways inexplicably, come back.