Apps as Collaborative World-Building

Minnesota artists leveraging digital technologies—from tools for drawing Black hair, to spaces for VR, to dream artistry, to digital drawing—to create the worlds they want to see

The ever-ubiquitous application, or app, is defined by Technopedia as “computer software, or a program, most commonly a small, specific one used for mobile devices. The term app originally referred to any mobile or desktop application, but as more app stores have emerged to sell mobile apps to smartphone and tablet users, the term has evolved to refer to small programs that can be downloaded and installed all at once.”

Social media, gaming, and communication make up most app usage, but as mobile technology weaves itself ever more into the fabric of our daily lives, increasing aspects of existence seamlessly sync to the invisible lines of code. Unlike usage and users, code, in and of itself, does not lend itself to ethical inquiry. Indeed, we have seen how the giants of the attention economy have attempted to sidestep responsibility for the social harm their algorithms have and continue to inflict by, in part, claiming that discord was never their intent—and besides, lines of code don’t radicalize people,1 people (or some other forces elsewhere) do.

So why bring all of this up in an article about apps and art? Being so integral to our lives, the ultra-mundane app is not readily recognized as bona fide art. Despite the wondrous beauty and care with which my meditation app has been crafted, I don’t reckon to see it anytime soon (or ever) featured on my next visit to the Tate. But after talking to some Minnesota-based artists, I start to suspect that I may be wrong, that some version of this scenario may indeed come to pass. If you look hard enough and think long enough, the deep past and the near future intersect in the living present: including race, representation, dreams, entrepreneurship, embodied practices, collaborative world-building, sustainable digital economies.

What we talk about when we talk about apps

Before moving on to how some Minnesota artists shape and are shaped by their creative technologies, I’d like to first clarify my use of certain terms. As the technical definition of apps given above has shifted to meet the new reality of smartphones, the use of apps by artists has shifted. (For our purposes, the terms “software,” “app,” even “tech,” can be thought of interchangeably—our interests lay less in the precise fixing of context-volatile terms than in the cultural production of artists.) Photo editing software is now as ubiquitous as the No. 2 pencil. Tech use by artists runs along a spectrum, from the given (such as photo editing, touch-up, and manipulation or digital drawing programs) to the more sophisticated (3D programs, 3D printing, special FX) to the emerging technologies of XR, AR, VR (Extended Reality, Augmented Reality, and Virtual Reality, respectively) and beyond. The artists I talk to below span much of this range.

Perhaps it can be argued that the arts and advanced tech have tangoed since the days of Da Vinci, or certainly since the early 20th century. Yet our cultural conceptions of technology’s role in creativity and vice versa, in the most visible arenas—museums, galleries, public spaces—are still greatly unshaped: we can expect to go to a contemporary art museum and see something hanging on a wall or sitting in the middle of gallery space, but don’t necessarily feel that something is missing if no AR is on offer.

This is unlikely to remain the situation for long. For example, Bjork’s 2011 album, Biophilia, was the first app added to the Museum of Modern Art’s (MOMA) collection in New York City. Wrote MOMA senior curator Paola Antonelli:

“Biophilia—a hybrid software application (app) and music album with interactive graphics, animations, and musical scoring—reflects Björk’s interest in a collaborative process that here included not only other artists, engineers, and musicians, but also splendid amateurs—the people that download and play the app/album. Upon opening the program, players encounter a galaxy punctuated with 10 songs represented by brighter, colorful stars. Touching a star launches a mini-app in which one may both listen to and contribute to a song.”

While there are surely many Minnesota-based musicians doing interesting work with tech, I have limited myself to reaching out to artists who work more in the visual realm. This is not to say that audible/musical elements won’t be found in their work.

Invention is the Business of Necessity

Alongside the continuous deaths and deprivations exacted by the ongoing COVID pandemic, pockets of positivity can, if one looks carefully enough, be found. After all, hope and silver linings are part and parcel of what, in less cynical realms, we call the human spirit. This is what I discovered when talking to artist and young entrepreneur Vegalia Jean-Pierre.2 “After being a professional photographer for about three years,” she explained, “I pursued art again once the pandemic hit.” Lockdown led Vegalia to acquire an iPad and start (again) on her digital art journey.

Though Vegalia’s passion had always been art, her high school advisor convinced her to pursue a non-art college major. After taking business courses and studying entrepreneurship, she moved on to product design, “because,” she explained, “that still had the art elements in it.”

Vegalia found herself using drawing software like Procreate, but found that the brushes available for creating the hair texture the Black subjects she wanted to create either didn’t exist or proved inadequate to the task. “It was my own problem that I was facing when I was drawing different hair styles,” she said. “I made a character that had micro-braids and it took me four hours to draw that by hand, they were so tiny. In my own personal work, I didn’t want to stop drawing characters with Black hairstyles that were harder to draw just because it took a lot of time.”

Instead of cursing the darkness, Vegalia lit a candle. “So then I researched ways that it could be easier and found out you could make brushes. I had someone else’s and I didn’t like them, so I decided to innovate and design my own.” Soon after, perhaps inspired in part by the business classes she had taken, and having realized a real-world need, Vegalia realized she could sell the brushes. With the encouragement of her supportive social media audience, she did just this under Brushes by Vegalia.

And the need was real indeed, as the brushes (or rather, Vegalia’s social media videos of the brushes) quickly went viral and garnered millions of views. This led to her becoming one of ten recipients of the inaugural MACRO x Tik Tok Black Creatives grant, giving a $50K boost to her business development. Now Vegalia is expanding from brushes and creating more digital products to increase positive representation for people of color, supporting other artists by collaborating with them on these projects. That global software companies, with access to sophisticated marketing data, never considered how a large chunk of their users would want to draw people with non-white or non-Eurocentric features, reflects broader social realities. “My audience,” said Vegalia, “I really listen to them and what they want, what they’re seeking in the world—and that’s how I developed my curl brushes, because someone said, ‘No curl options, can you make some?’ That the software could be used this way seems simple enough. Would any of the companies try to make this right? I prodded Vegalia to speculate. “They might have eventually done it, but it wasn’t at the forefront of their minds because maybe they didn’t experience that themselves.”

The Coming World of VR in Our Backyard

REM5 physically occupies 8,000 square feet of commercial space in St. Louis Park, Minnesota. But their focus and future lay in the realm of VR and XR. REM5 Director of Marketing and Events Brian Skalak explained that, in the digital and VR space, it’s a more open and unsettled world “than the more traditional mediums.” REM5 is where the fast-changing digital and virtual space can be grounded IRL, so to speak. “The Twin Cities is a great market if you make paintings. There are a billion art fairs and galleries that would happily show that. But there is a whole number of zero getting more into the digital space where artists can showcase that type of work in the real environment, rather than just posting it to the internet.”

Skalak explained that REM5 offers three important elements to engage the uninitiated general populace into the world of VR: (1) a large physical space for artists and participants to gather, something harder to come by these days; (2) the highest quality comfortable headsets and hand-held controllers; and, perhaps most importantly, (3) the staff, who are trained facilitators and VR educators.

“I want to bring people out to an art event who would never go to an art event,” said Skalak. “I want to build experiences and an event that I would want to go to, that feels more inviting and more fun. You can touch stuff, you can break stuff, you can play with stuff.” The hope is to build a community of artists and audiences around events, such as their Experiential Sensory Collective (ESC) XR Art Series, which was started in the spring of 2019 and subsequently sidetracked by the current pandemic, but is now back on.

The vision of engaging the general public started with engaging artists in this digital uncharted territory. Skalak related: “Amir’s [Amir Berenjian, one of the founders] big play when he started REM5 was, ‘How do we get traditional artists to come over and try VR, completely free, no strings attached?’ Maybe ten people would come over, and two of those people would be like,‘This is going to change everything I do with art. This is what I’ve always wanted—three-dimensional, you can play with scale, you can make a piece of art that can’t physically exist.’ And so, for a lot of people, that was really exciting.” More time was scheduled for such artists. For artists cooler on the technology, no harm, no foul.

Although it seems obvious, it bears making explicit that culture requires sustained action and engagement in order to grow. Oftentimes, the future is caught in whispers and appears distant, until it isn’t. “I think there’s a lot in the VR space, and especially the metaverse space—it’s a lot of hype and a lot of talk, but not a lot of doing,” noted Skalak. “We try to be the exact opposite of that.”

“It’s what’s coming, so the problem is, if you’re not on board you’re not going to stop it if you feel a certain way about it. And that’s why it’s not for everyone, just like other kinds of art and music aren’t for everyone. The people that get really excited about this love it, and that’s what’s important.”

“The ability to go inside of something and have it all around you is just incredibly novel. Nobody’s painted in spherical 360, to my knowledge, so the fact that I can put you in a headset and transport you to a completely different world that your brain will interpret as real—that’s the whole reason for the business. For the naysayers or the unsure, they just gotta try it.”

Dream Artist in the Digital Realm, or Embodied Practices and the Future of Drawing

As someone who has been deeply involved in the physicality of art for much of her adult life, from calligraphy to painting to printmaking, Sheila Asato’s artistic journey has recently led her to the world of VR via REM5. (Her studio is Monkey Bridge Arts.) But it makes some kind of sense: she’s also a dream artist. She had originally gone to Japan to study art by medical necessity, for then arts material was toxic, whereas in Japan they were all water-based. “Back in Japan I had this dream—you know, a literal one at nighttime,” she said, “of being able to create art that people could walk inside of.” After moving back to the States, she came across the Minnesota Book Arts Center, where she learned to create different structures, such as the Jacob’s Ladder of her dream. A fellow book artist there convinced her to connect with the folks at REM5. Asato thought VR would be a distraction; after all, she had sons and knew something of video games.

She also knew something of, and is a strong believer in, embodied practices:

“When we have embodied practices—if it’s dance or if it’s music, if it’s working with the physicality of materials in the visual arts—you can’t do something else at the same time. You have to cultivate attention; that’s a basic part of the skill set. You can only do attention if you are using your full body. That attention doesn’t happen in the mind alone, in the brain alone, while looking at other things. The mind is super fast—thoughts are fast, images are fast, and unless we concretize them and spend time with the limitations of materials, whether it’s an instrument or if it’s our body if we’re dancing and moving, it goes too fast.”

So it may sound counterintuitive when she describes her first VR session at REM5. “I put on a headset and tried Tilt Brush,” she recounted. “I thought, ‘Whoa, this is so cool.’ After a while, I said, ‘My controller, it’s not working anymore,’ and they said, ‘Sheila, you’ve been in there six hours, the battery died.’”

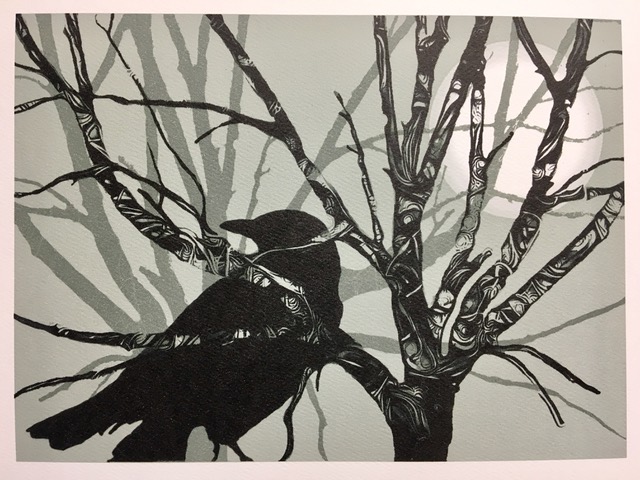

So she went from dream to book arts to VR to dream-VR. “After creating Raven Moon [her first VR project], this was really interesting—my dreams were so excited about me trying things in virtual reality, because I was getting loads of dreams and support through that. I thought ‘Okay, I’m curious about this connection,’ so I asked him [Amir], ‘What do you think about that? Could I work as a dream artist here? There’s never been a Dream Artist in Residency anywhere in the world that I’m aware of, or any of my colleagues are aware of.’

He said, ‘Sure, let’s see what happens.’ So they helped me with the technology, and I let the dreams help me with figuring out how to do the process and content development, and that’s what’s been happening.”

Then the pandemic hit. Fortunately, Asato was able to obtain a PPP loan to create a VR room in her studio, where she continued to work.

Far from taking her further from her material artistic roots, Asato has been able to venture more deeply into her old dreams and projects. In fact, she still talks about virtual spaces in terms of books. “What I noticed, though, is that it opened up this idea I had, that I could actually create books that people could walk inside of, and I could make it inside this world where they could initiate how to move through it.”

Asato noted an influence of hers, David Hockney, who she paraphrased as saying that, in some ways, digital technology is what will bring drawing back.

Virtual Age

Asato noted the impact that new technologies have had on her ability to stay as creative as possible despite aging’s concomitant declines. Instead of now having to lug large, heavy materials around, using digital media allows her to enlarge things on her iPad despite her changing eyesight, adding: “I don’t care what media I work in, as long as I can stay creative and keep learning.”

Being on the cutting edge of VR, since it’s so new, one doesn’t need to ask permission to participate. You just do it. “Which is the not the experience I’ve had in the States with technology, where I get dismissed a lot because of my age,” said Asato. “In the world of virtual reality, it hasn’t mattered at all, and that’s been wonderful.”

While digital technology may be bringing drawing back, while also allowing older practitioners to continue working in the medium, the skills a person needs to cultivate may not be so readily available as an app in an online store. “What I found out was that a lot of the younger artists, in their training these days, it seems they’re spending so much time on technology they don’t get as much time drawing and stuff as I did. They don’t necessarily learn visual thinking with their whole body.”

For Asato, a large part of the connection between visual thinking and embodied practices has to do with attention—or lack of it: “If you use VR to disengage from the physical world and disengage from the body, then you’re also going to disengage from attention. I think it leaves you in a very vulnerable place. Fractured attention can be very dangerous to ourselves and to others and there’s nothing health-wise to be gained from it. I think all new media—it’s not just virtual reality—all new media, when we get entranced with it, can take us someplace else.”

Building the World We Want

About a decade back, Paige Dansinger (Better World Museum, Horizon Art Museum), used the app Draw Something to draw digital versions of works from museums, a project that would become known as Museum Draw.3 After dedicating herself to creative technologies, she developed, with help from the local community, her first app using open-source code. “I made my first drawing prototype, and with it I drew over 4,000 works of art from museums,” she said. “Some of them ended up at the Guggenheim, and presented at the Met’s Media Lab. I was part of a colloquy for the Parthenon Restitution Meeting. They were shared around the world.” This sort of gateway app project led her, around three or four years later, to VR—or more precisely, to the Met Media Lab’s new-fangled VR rig area, while she was presenting there. Headlong into the digital frontiers she plunged, building, growing, and giving.

From 2018 through 2019, Dansinger was a member of the Facebook Leadership Training Program, where she carried out a project that had both real-world and online impact; she took her VR garden to places such as the US East and West Coast, China, Cambodia, and Singapore. “We were a climate and community resilience museum,” explained Dansinger. “I focused on communities that were facing climate impacts that were also part of my community leadership network.”

Dansinger’s work in the burgeoning VR world straddles three core themes that don’t merely mirror by analogy our IRL world, but show how inseparable the digital world is from non-digital entanglements: (1) collaborative world-building, where multiple participants use basic virtual building blocks to build a shared virtual world; (2) sustainable digital economies, where digital technologies are employed toward (real-world) sustainable development goals; and, (3) charitable giving, where causes Dansinger cares about can get wider attention and support.

Collaborative World-Building

For Dansinger, reworking digital elements can clarify what sort of real world we want. “Collaborative world-building allows people to use fifteen primitive shapes, gizmos, and block scripting, and really reshape their lives—but also their vision for what makes a better world for them,” she said.

She cites, for example, hackathons, where creatives and technicians of the digital space work in teams on challenges, as somewhere “people can solve problems, with neighbors, in a group, especially with people they consider “other.’” The IRL consequences: “All the things that our community faces can be done [via hackathon-like exercises] way before there’s calamity. So by creating a community garden or whole city infrastructure or edible corridor, we can use our museums as sites of social actions.” And she interrupts herself with a highly pertinent consideration: “What harm can it be to make a bigger board room table?”

When asked if she had any concerns over how much of this collaborative space is corporate-owned, she explained that she liked all the tools, even if they’re corporate owned, so long as she can use them to support her primary mission of putting people first. “So long as the tools are used thoughtfully, mindfully,” she elaborates.

Sustainable Digital Economies and Charitable Giving

Dansinger goes so far as to say that community world-building is community building. “VR can be a huge push in that direction, more altruistic interactions,” she says—for example, climate hackathons that attempt to solve specific aspects of the climate emergency. “It’s not just an app where you engage and disengage, it’s social VR, you’re meeting with a couple of your friends, you’re collaboratively world-building, and you’re going to events that are raising presence and awareness for issues that are relevant today.”

While Meta (formerly Facebook) has been supportive, for Dansinger, “at the end of the day, it’s really about the mission, the people, the community, and no corporation can override the importance of the open nature that can create more authentic representation in communities, more empathy, and more action, even.” Some of these efforts have included her Purple Flower Survivors supporting survivors of domestic abuse and various collaborative projects within Women in Horizon Worlds.

Sometimes the app is too close to us—such as in our pockets or behind every digital screen we encounter—to be clearly seen, something easily taken for granted like a long-time partner or family member. We forget that we didn’t have such things at our disposal only a few short years ago. And now that we do, we tend to forget that they are tools that, yes, we want implemented for their intended purposes. Soon enough, we forget that they had ever been tools in the first place; they are just what they are. We find it difficult to think beyond their current functions to imagine what other real needs and wants they might fulfill.

Then there are apps so outside school that, surely, we won’t be caught dead using X [insert new technology here]. Until, of course, we are.

Our attention can be drawn to the latest trend or viral cat video (nothing against cat videos, a huge fan myself) and usually it is. If we believe the marketing, apps exist to make our lives easier, not to make us work harder. But that’s exactly what artists do: take the world-material that is and reshape and transform it—at the cost of much time and effort. Thinking of apps in our lives the way artists actively and mindfully do is a reminder that we are ultimately not condemned to be passive users in a world increasingly shaped by algorithms. Sure, we can opt out and make immediacy great again, but this appears more the fantastical than practical approach. Another option may be to opt in artfully, in both the dictionary and thematic meanings. For art and technology all bore down into the same crisis: how to (co)exist as human(s). Only a fool or tech billionaire would claim that there’s an app for that.