A Hymn for Art, Beauty and Faith

Camille LeFevre parses the recent performance, "Devotion," a provocative new dance work with powerful religious and spiritual overtones by Sarah Michelson and Richard Maxwell, recently on stage at the Walker Art Center.

OF THE MANY DISCOURSE-INSPIRING, ARGUMENT-INDUCING ASPECTS inherent to New York choreographer Sarah Michelson’s work, one characteristic overrode all others after I experienced her thrillingly iconoclastic piece at the Walker Art Center, Daylight (for Minneapolis), in 2005: Everything Michelson does is deliberate. Her vision and her intention are total, all-encompassing.

Of course, she’s intentional about the performers she selects, the choreography she gives them, and what they wear; the art on the walls; the music coming through the speakers; the light and colors and staging and ways in which they clash or integrate. Most dance makers are. But Michelson is also after a specific effect, meaning what happens on stage is designed to happen to you, dear audience member.

You’re part of the performance, and your feelings of discomfort, outrage, enjoyment, bliss, boredom — or whatever other emotion or sensation arises as you watch — have been deliberately elicited by Michelson and her work. From what you’re allowed to see and how you’re allowed to see it, to where you sit in the theater and how you squirm in your seat — it’s all part of her plan. Which is why Devotion, Michelson’s collaboration with Richard Maxwell (artistic director of New York City Players, who wrote the text of the piece), performed at the Walker Art Center last Friday and Saturday, inspired more questions than it answered — just as religious devotion, come to think of it, does in the faithful.

The archetypal stories of Christianity (Adam and Eve, Jesus and Mary) are the basis of Maxwell’s poetic, personal, memory-inflected text, narrated by Rebecca Warner in seven chapters at the beginning of the two-hour Devotion, and as an epilogue. The choreography is a precisely executed blend of ballet, yoga, and everyday movement (running, walking), performed by Jesus (James Tyson), Mary (Non Griffiths), Adam (Jim Fletcher), Eve (Eleanor Hullihan) and Spirit of Religion (Nicole Mannarino). Their performances are by turns heroic and banal, punishing and ecstatic, urgent and trancelike, severe and gentle.

The temperature inside the theater, even before the performance begins, is exceedingly warm–on purpose, no doubt; the heat intensifies as the performers sweat through their shirts, shorts, pants, and swimwear during rigorously executed, marathon sequences of repeating patterns, steps, leaps, and runs — often to Philip Glass’s iconic “Dance IX” (the music for Twyla Tharp‘s 1986 In the Upper Room) — as lights flash, bear down brightly, or swing precariously in a cluster hanging from the ceiling like aluminum apples shaking on the Tree of Knowledge in the Garden of Eden.

Michelson isn’t about to let the audience sit in comfort while the performers work. We, too, are required to endure as penitent observers of a singular heaven/hell. Heaven resides primarily in Mannarino, a cliff climber and dancer of supreme self-assurance, athletic virtuosity, and muscular intention. In her lengthy and exacting solo of leaps, lunges, crouches, poses, and turns, which opens the piece, Mannarino embodies a kinetic mysticism that conveys the rigors of religious faith; it’s a solo in which one becomes “lost in the pleasure of the perfect,” as the text suggests.

Mannarino’s sometime partner — who isn’t named in the program, unless she’s Alice Downing, who’s billed as “assistant to the choreographer” — and Hullihan are, like Mannarino, supremely heroic. Their expressionless faces, athletic physiques, impeccable timing, and flawless execution give them an uber-woman quality. They might, at times, be angels. Hullihan, as Eve, is certainly calling the shots in her dealings with Adam.

______________________________________________________

Devotion is extreme. It’s epic in scope, duration,

and the endurance required of performers and audience.

______________________________________________________

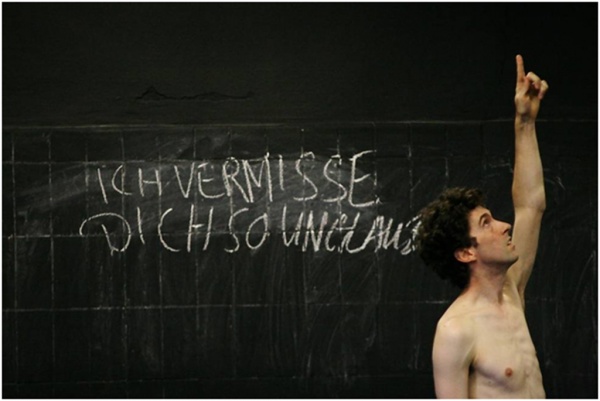

So what are we to make of the men and, particularly, of Michelson’s decision to cast Tyson and Fletcher? They’re actors, not dancers — and it shows. Compared to the amazons among them, they’re clearly lesser physical beings. They do provide some support for their partners — this is especially true of Fletcher, as Hullihan exquisitely tosses herself at him over and over again. But when Fletcher takes off his shirt, what is Michelson’s message: anti-physique, anti-beauty, anti-expectation, anti-dance?

Moreover, for what reason did she cast the anorexic, 14-year-old Griffiths as Mary? This child-woman is so painfully, excruciatingly thin, to call her limbs twig-like is generous. She moves unflinchingly, like an automaton, and with brittle ferocity, through her long solo of abruptly truncated choreography. As she falters when she should land or stand stock still, her panting becomes audible and her face reddens dangerously, and such questions arise as: What sort of self-punishment, flagellation, or mortification does she represent? And why this girl, with her obviously ascetic appearance? Is she a fetish of some sort? Shouldn’t she be home with her parents, enjoying a nice dinner followed by a banana split and some television or texting with her friends, instead of exercising (or exorcising) herself to exhaustion — or worse, undergoing this ritual for the benefit of an artist and her art?

Meanwhile, Michelson presides over the proceedings from various portraits featuring her inscrutable expression — painted by TM Davy in the vivid, rich style of the Old Masters — hanging on one side of the stage; the other side is a black box with curtains.

Devotion is extreme. It embraces the everyday by costuming the performers in color-coordinated sportswear. It’s imbued with the formalism of composition (choreographic and otherwise) and the ritual of performance (art and religion). It’s referential both to dance history — not only to Tharp, but to Lucinda Childs in the use of repetition, pattern — and to Glass’s music. It’s epic in scope, duration, and the endurance required of performers and audience.

Devotion is a hymn, of sorts, on art, beauty and faith, by which one is left breathless and disturbed. “Undivided. Voluminous. Yours,” intones Warner, reciting Maxwell’s final words.

Discuss.

______________________________________________________

About the author: Camille LeFevre practices and teachers arts journalism, which she blogs about at camillelefevre.wordpress.com.