What I’m Doing When I’m Not Writing

On fallow time, cycles of making and not-making, and what the body invites in while holding language at a distance

I am making a spinach smoothie. I am picking at my ingrown hairs till they curl and rise like little worms breaking through the earth of my thigh skin. I’m tracing a figure into my skin with the rough edge of my thumbnail. This time it is an eel. No, this time it is a muffin on two long, spindly chicken legs. No, this time it is the sun but with sour little eyes.

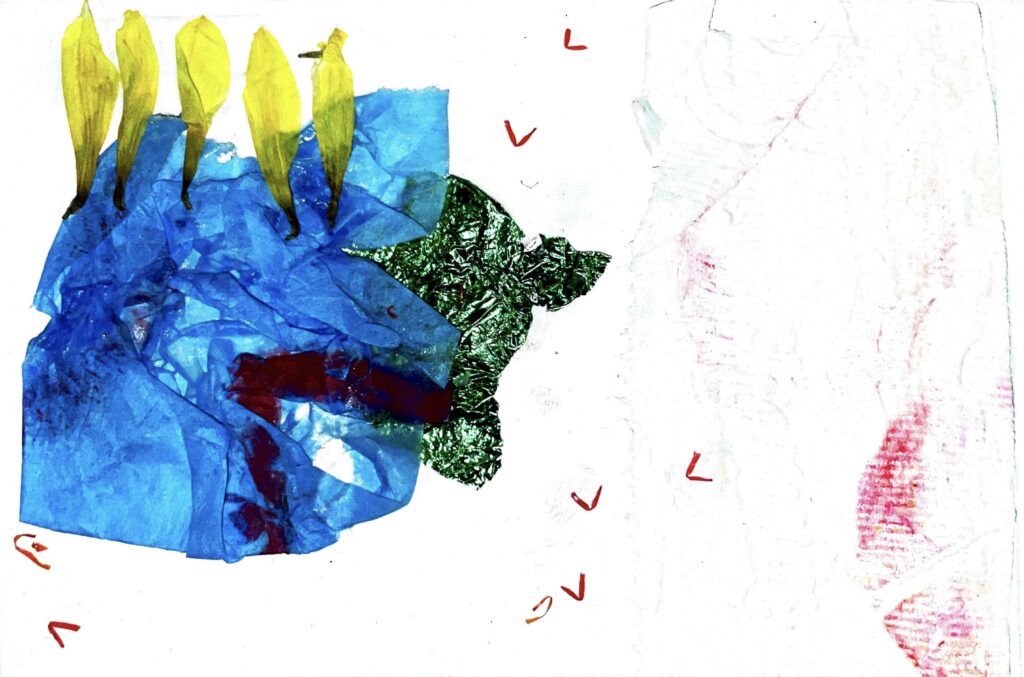

I am not writing, and have not been writing. I cannot write. I’ve been watching the dying flowers on my dinner table drop their petals, and dust the wood with pollen like impatient guests. I’m tugging on my pubic hair the way that I learned to when I was a bored kid, as if to say: I’m alive, and I can feel it.

When I’m not writing, my dreams are more vivid. Writing is one way that I access my dreamspace, that I channel parts of myself that are formless and stand outside of time into the mundane world. I feel clogged when I am not writing, like all of the electricity of dreamspace is building up inside of me and swirling, circling into erratic storms.

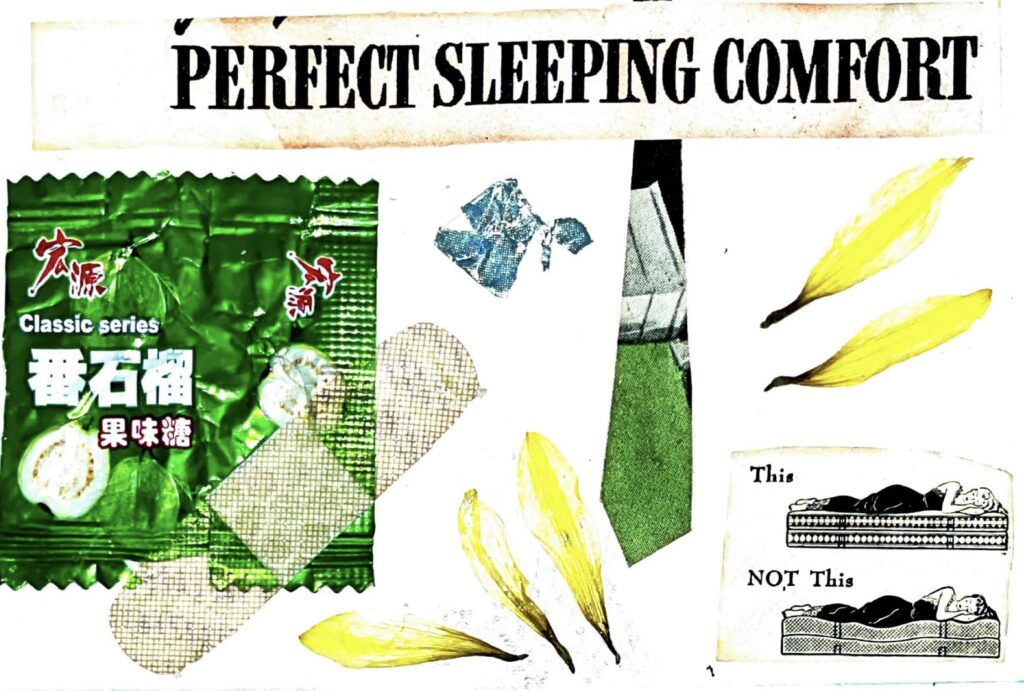

Why am I not writing? Because the sky has been the same color as the ground for four days and, before that, the last time I saw the sun, I got a headache. Because there’s a tiny storm living inside of my hips and I’m afraid that if I let it pour out of me, I won’t have any other sense of movement. Because grapes don’t taste as good as I remember. What is the square root of the sticky patch of grime that lines the edges of tile in my kitchen? Even though my dreams are more vivid, they are flooded with things like my French press or an interaction online. I wake up in a cloud of dust, pinch all the tips of my fingers so I won’t lose feeling.

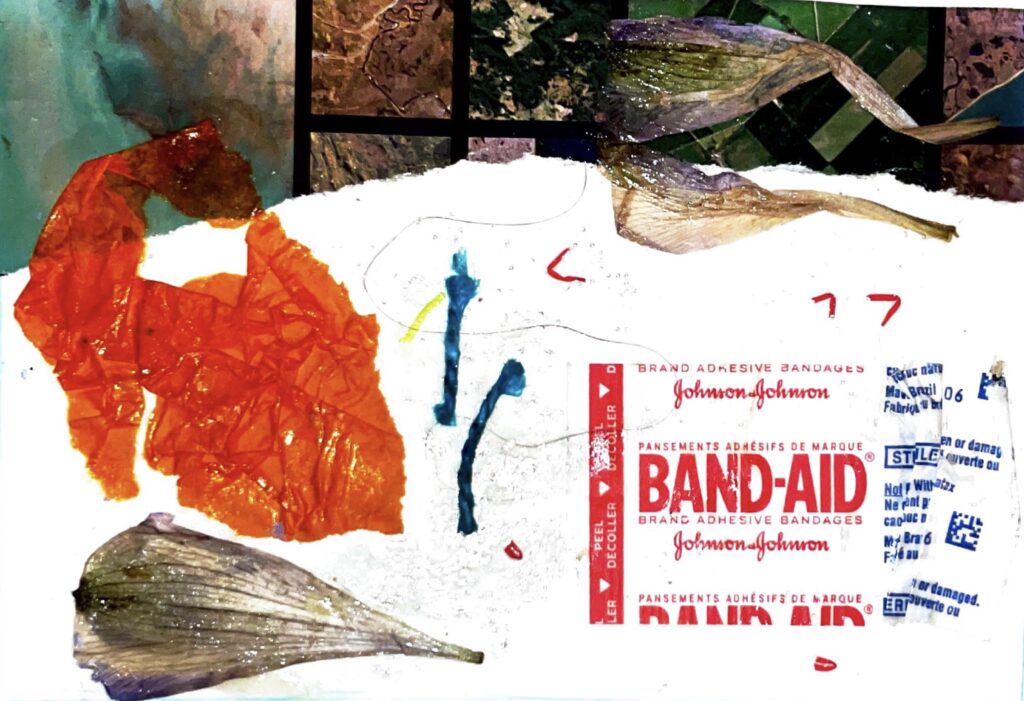

In her essay “Writing the Pandemic Slant,” Sandra Gail Lambert writes about working through her period of not-writing during the pandemic. She turns to the routine otherwordliness around herself in Florida, and reminds herself of the lessons of past periods of not-writing. She describes needing both the truth and magic, things that I also feel drawn to. As a chronically ill person, I know intimately my periods of not-making and understand that these periods are also a part of my cycle. I am not a poetry machine, I’ve said to myself before.

But my cycle, like many cycles on our planet right now, is changing. Like many of us living in Minneapolis, my body still holds the latent charge of the militarization of our city after the uprising and the ongoing brutality of MPD. I’ve changed so much since the pandemic began that the desires, griefs, and needs of the person I was then feel unrecognizable to me. My capacity for disappointment has bottomed out, and I’ve learned just how unrested I actually am.

Still, it’s not that I only believe in writing from a place of joy or ambition or spaciousness. In fact, I feel quite the opposite and draw on decomposition as a natural process, death, and filth in my own art practice. I am also not writing this piece in defense of hope. The essay “We Need Courage, Not Hope to Face Climate Change” by Dr. Kate Marvel is one of my favorite pieces on climate change, in which the physicist talks through the very mechanics of a distorted climate future and our own struggling emotional faculties. “I understand the physical world because, at some level, I understand the behavior of every small thing,” she writes, “The world we once knew is never coming back.” These last few years have made me understand myself as a small thing, too—at the whim of structures that are violent and draining, and at the whim of my own sick body making its own sense in a senseless world.

What I’m talking about is the physicality of writing, the intermediary process where the substance of the material world is alchemized. Working with language is like peering between my fingers, at times like making a fire. I am moving my body, scratching lines on paper, paging through my journal to transmute something about the world into a shopping list, a poem, a joke, a prayer. But it is so cold out now, too cold to do anything but embrace the winter sun’s harsh, golden discipline. I can’t layer my fingers fast enough; I have to see all that is, the wide blue and white expanse. So I’m writing about not-writing as a practice of feeling into the truth, or of telling the truth without language—which even poets know is a gestural tool, at best. What is language, but a map of voids? All the impressions that I am massaging into form to show you a possible world. With language, I can construct the shape of a thing, but with not-writing, I can show you that I am very tired. That my grief is now with me and of me, both a brother and a second skin.

Many artists talk about the fallow period as a necessary part of the creative process. Mimicking natural growth cycles, fallow periods are a time for rest and empty space. Especially after finishing a project or body of work, I look forward to the solitude and openness of my fallow time. I’m struggling to understand how this part of the cycle is shifting given the reality of mass death all around me. What is it called when something stays fallow? When what eventually grows comes back different, monstrous, world-weary and making its own demands?

I am wearing my grief in that it is wearing on me, too. And in the gesture of not-writing, I suppose I’m putting on a durational performance: what to do when the sinkhole inside of yourself opens and opens and opens. I’m not saying that I won’t write again—I mean, I’m doing it right now—but that I’m aware that my rhythms are irreversibly changing, as is what I can demand from my stamina and imagination now. That a fleshy winter has cracked its maw inside of me and begun to hunger for shadows.

In my dreams, I sometimes pick up a pen only to watch it turn into something I can’t write with: a spatula or an electrical cord. The fantasy is kept squarely in the mundane, and I’m often begging my brain to drum up something more fantastical. In a sense, it feels humiliating to me to be so bereft of my magic right now—but I’m learning that if I’m struggling with dreaming, I can learn instead to see and describe clearly what is in front of me. This is boredom. This is agony. These are tears stuck in my ducts for days, a bowl full of oatmeal softening in the dirty sink.

When the words come back, I’ll be sure not to apprehend them like old friends—but as travelers bruised from a long journey and skeptical of my authenticity. I imagine that I will have to gain their trust again, both the words and the ghosts that come with them. I imagine that there will be stowaways and tricksters who took the bodies of my old friends in the night, and I imagine that I won’t know the difference. And I’ll be there without flowers or weapons, but with open hands and a bowl of water. I’ll be there with a drum. I’ll learn how to make grief songs.