Jerayah: Making as a Catalyst for Remembering

Learning to recreate handmade wool mattresses, a family tradition from Libya to Israel, becomes a route to memory and connection

The Time It Takes

How come I love repetitive work so much? Taking wool out of the bag, opening it up while imagining the body of the sheep: where its head was, its back. The tail is easy to tell because of the stiff dirt. Rummage with your hands after particles of twigs, caught in the tangle of curls. Just like my own hair always gets particles caught in it. I remove them, like one removes lice, gently and scrupulously. It takes time and I like the time that it takes. The work day is over.

Passover 1987

I don’t know since when I have remembered the celebration of Passover night Seder.1 I do remember how eagerly I awaited the event. There was nothing alike between the Passover that I knew and the one my classmates were familiar with, even though most of them probably celebrated it with their families in one way or another. Dad would open Grandmother’s house door (you never knock on the door, it’s always open in case guests arrive) and immediately there would be joyful shouting of welcome: blessed be the coming, bruchim ha-bayim! We’d be dressed in our finest, but we carried our pajamas in plastic bags, and we’d switch into them almost right after arriving. The living room floor was covered with heavy wool mattresses. All the weekday furniture was gathered into one room and shut away; instead striped mattresses were spread along the walls on the floor. We did not have a suitable table, so two doors were removed from their frames, laid on building blocks, and covered with a white tablecloth, forming a low and long platform.

After the kissing chapter was over, I’d change into my pajamas so that I could stretch on the stiff mattress between my uncles and cousins and play. I retained no memory of reading the Haggadah,2 except for the more theatrical bits, those in which us, the little ones, participated alongside the grownups. I remember the huge aluminum bowl that contained all the blessings. Grandmother would pass through with the bowl and we all, big and small, would offer our heads, so that she’d gently tap the head with the bowl and bless. Then a gigantic lamb leg was raised high in the air and passed between the guests, everyone saying, “By a mighty hand, by an outstretched arm.”3 All that was happening in the mayhem of children playing, teenagers chatting on the balcony, adults talking to each other. All in a small, state-owned apartment, two bedrooms and a living room in Tirat Ha-Carmel.4

On the Floor

I remember the excitement I felt being on the mattresses on the floor. The transfer from sitting on a chair to reclining on the mattress, relaxing with all the rest of us, the time halts, no hierarchy, a baby laying on the mattress while her mom, seated beside her, reads from the Haggadah. You just had to pay attention so no one steps on the babe by mistake. The Haggadah that the elder uncle was reading from came all the way from Tripoli. Our grandfather had died, so his eldest son took upon himself the role of the father (the steward) of the Seder.

Grandmother Wassi made ג’ראיה (jerayah)—the mattresses—by herself, using sheep wool, just like her mother used to make them in Tripoli. In Libya and Iraq, girls were taught textile crafts from a young age so that they could start preparing their dowry early on. Wool mattresses for the young couple were part of the dowry, especially in wealthy families. The mattress also figured in the after-dinner communal tea drinking ceremony, when the room was laid out with straw mats and the mattresses were placed on top, forming an arch-shaped sitting arrangement. The mattresses in turn were covered with decorated spreads. The tea was served in three glasses: first: the bitter, second: the sweet, third: with caramel and peanuts or almonds. Aunty Mazal remembered that the caramel tea was very dark brown, because of the burnt sugar. Aunty Hannah remembered her own aunt, Rachel, spreading the mats on the floor and pouring tea from an aluminum kettle. She also brewed a special coffee for the kids—it was made primarily from chickpeas.

Being a kid, one doesn’t really know when the evening is over. It always feels like something continuous and joyful that is over when you fall asleep on the mattress between your cousins. Much of the Haggadah was read in Tripolita’it5 anyway, the language of Jews in Libya. Written with Hebrew letters, but sounding Arabic, it was a language the youngsters born in Israel could not understand any longer. We kept celebrating in this way every year until my mother decided that enough is enough, that the children have grown and brought their own children now, and time has come to celebrate the Seder at our house with table and chairs.

By the way, my mother used to complain about the Seder night. She’d say that dad’s family behaved like they were still in Tripoli, and it’s time to move on. Generally she didn’t like the noise and the crowding. By the way, we’d always visit her family briefly (30 minutes on the clock) and then continue to dad’s relatives. At her parent’s house everyone sat around a table. It was quiet, and for a kid, very boring.

What is kept in our memory and what is left out? The body decides what to retain and what to dissolve, and in what part of the self to save that which was retained.

Mother

Recently my parents came to visit us in Minneapolis. Four years we haven’t seen each other in person. In a late-night conversation in our living room, my mother expressed her resentment about the art project that I did, that it was only about Dad’s family, that I’ve never taken an interest in hers. She also told me that before she joined Dad’s family for the Seder celebration, their custom was that all the men and boys would read the Haggadah and take part in the rituals, while girls would sit in the balcony and just talk to each other. They were not supposed to be part of the Seder. She insisted on changing that.

Despite the Pleasure

We moved to a new city just recently. How many times have we moved since we came to the USA? I hope that this time it is a place to settle down. Seven months have passed since our move and everything halts, a global panic from the pandemic. My son has just begun attending a new kindergarten, and then it shuts down. We get lucky, because we bought a house just one month before and moved there from the university accommodation. Despite the pleasure of the coming spring and the free time that lands on me, that I dedicate to tending to our garden, slight anxieties begin to rise as I look at us: it’s only the three of us here. Newcomers. The family is so far away. What will we do if something happens? If one of us falls ill?

I buy a sewing machine. I yearn to sew things for Oliver, my son. Something joyous, reassuring, like a purse to keep his collection of stones or a pouch for his favorite teddy bear. This has become my favorite pastime. How come I don’t take as much pleasure in doing my art as I do with sewing this purse? I feel guilty about this. I remember that just a while ago, there was nothing more pleasurable than being in the studio.

Liza

The activities of sewing, and the intensive work in the garden when Oliver is beside me, bring up in my mind the feeling of complete freedom that I experienced visiting my dad’s family in moshav Hatzav.6 Two of Grannie’s Wassi sisters, Aunty Liza and Aunty Ester lived there. They’ve been constantly preoccupied with cooking, laundering and farming. For a kid it was the best place, because no one told me what to do or how and when or where to go. I could do nothing the entire day and no one cared. I’d wander outside with other kids from the moshav. We’d invent games. When I had enough of them, I went to look for Aunty Liza and just be close to her. No matter what she was doing, I loved watching her work. I thought she was this quiet angel with long gray braids and long dresses who knew things that no one else did.

On Aunty Liza’s kitchen table, innumerable candles were burning. Every candle was a prayer for someone. Once I stood by her in the morning when she was lighting the candles. At that time, my dad was in a lot of trouble, so one candle was for him, to aid him in overcoming the difficulties and the debts he ran into. Aunty Liza knew about everyone’s troubles and she devotedly lit the candles and prayed for us all. In the moshav’s synagogue they dedicated a special back room for her to light the candles and pray. Dad told me that at her funeral the procession passed by that room so that she could take her last parting.

Once the vacation week at Hatzav was over, my parents came to collect me. Aunty Liza accompanied the vehicle by foot with a water basin in her hands, spilling the water to make our journey home easy, as easy as flowing water.

Travels

My son is five years old. He knows nothing of all this: the Seder night, spilling water, mattresses… He knows nothing because we’re too far away from the family and also because nothing is left of those rituals in my life. Maybe I moved away from my birthplace not for the sake of new opportunities, as I usually tell myself, but just not to face all those conflicts within me, between the attachment to my dad’s people, the attraction and love I feel for their traditional rituals, and the modern academic ambition I encountered from the side of my mother’s family.

When my parents were about to depart for the airport, with all their suitcases loaded into the trunk, I found the courage to tell my son about spilling water for an easy journey. And so we did it together, spilling water after the departing vehicle—a blessing for fortunate travels.

As I Watch

I watch my son jumping in the living room, preoccupied with imaginary characters, ignorant of the fact that he is being watched and of the thoughts that cross my mind, how guilty I feel that I deprived him of the family heritage when I moved away.

Can I create something for Oliver that will give him some idea about those things in the family’s past and his own personality that he cannot access being here? Some kind of object whose presence and essence will alter with time passing, some new layer that will be added and transmitted to him, though the senses, in stages, over time?

But what do I know about my own past, about the generations before me?

The Voyage to Pipestone

A while ago I went to Pipestone. I wanted to learn about catlinite, the soft reddish stone Native American people mined in this location to carve ritual smoking pipes. I wanted to experience the place they consider sacred. For two days I was working with the stone, guided by Bud and Rona Johnston,7 a couple who took upon themselves to actively preserve this Native tradition.

Bud was telling about his search for people who remembered the rites, songs, and stories, and how difficult and sometimes impossible it was to find parts of a lost culture. I asked him, “So what do you do? How does one perform a ritual that no one remembers?” His answer was surprising. He sighed and said, “You invent. What else can you do? You put your trust in your intuition, you let it lead.” His words were a great relief to me. I can trust myself to invent the missing parts of the culture I came from.

Jerayah

In the search for a vehicle to transfer the experience of my family rites to my son, I thought of the wool mattress similar to those my grandmother used to sew, the ones my dad slept on as a boy, and the same ones we used to sit on during the Seder.

What if I tried to make one? How to approach this task when I am far away from my family, my grandmother died long ago, and not a single one of the mattresses that she created had survived?

I try to remember. The mattress was thick and densely stuffed with wool fibers. It didn’t sag when you sat on it, it carried the weight of your body. My dad told me he hated shuffling the mattresses because they were very heavy. Their fabric had lengthwise blue stripes. I learned that their distribution is there to direct the hand-sewing to remain in place, just like the blue lines on the writing paper direct the letters.

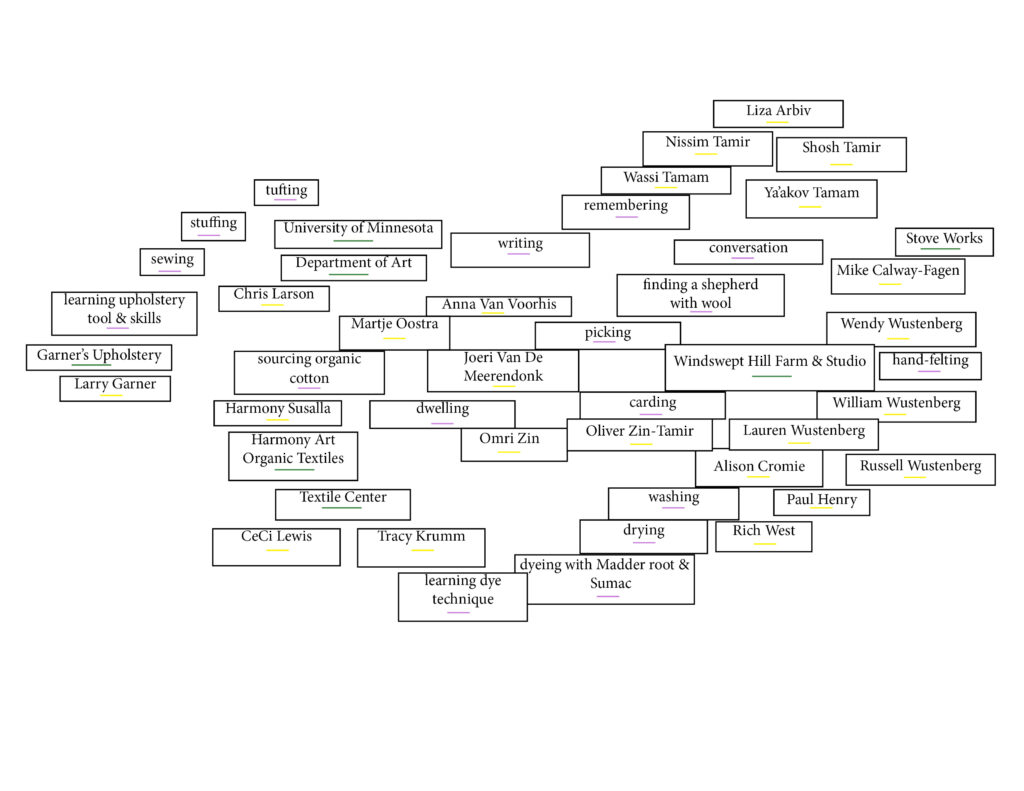

The mattress was tufted, so that its surface was undulated. I loved sliding my fingers over those surfaces as if they were valleys and hills. The tufts held the wool together and prevented it from lumping. As I’ve soon discovered, preparing the stuffing wool is the most laborious part of mattress making. Cleaning, scouring (washing), drying and brushing of wool are massive physical tasks that demand long days and collective effort. I found the collective at the Windswept Hill Farm & Studio,8 with Wendy Wustenberg and her family. Wendy welcomed me and generously shared her skills and knowledge of sheep wool fiber. I wanted to get as close as I could to the source of wool and to the fundamental making processes at the heart of the mattress. Wendy opened the door.

Windswept Hill Farm & Studio, 2020. Photo: Wendy Wustenberg.

Sheep shearing at Windswept Hill Farm & Studio, 2020. Photo: Lauren Wustenberg.

Sorting wool, 2020. Photo: Lauren Wustenberg.

Wendy Wustenberg, owner of Windswept Hill Farm & Studio, 2020. Photo: Rotem Tamir.

Picking out particles (first stage of wool cleaning process), 2020. Photo: Lauren Wustenberg.

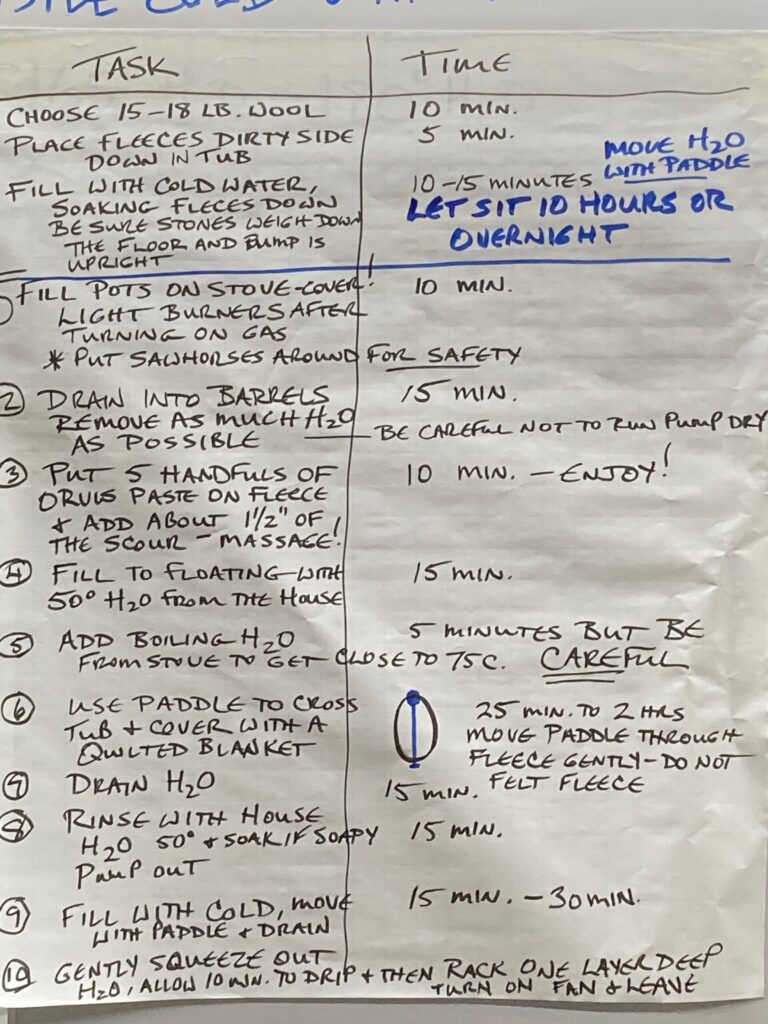

Workflow for wool scouring, 2020. Photo: Rotem Tamir.

Scouring

We started scouring in the late fall, after a great deal of manual cleaning activities, like picking out burrs and dirt lumps, were completed. We laid the wool sheared from two sheeps in a huge basin that originally was used to serve water for horses. It was getting colder outside, while we were spilling buckets of boiling water into the basins. The wool released a strong smell of sweat. The water turned black in the basin that meanwhile got covered with snow.

As I watched the wool soaked in black water, thoughts and images of the Holocast came to haunt me and I felt ashamed. How come this is what I think of when surrounded by warm and supportive people in this beautiful place? How come this is what comes up when I am engaging in the making of an object conjured up by the memory of my beloved grandmother? This prolonged and laborious collective work brought everyone who participated closer; we all shared memories and reflections. I chose not to share the horrors that visited me.

“We shall not be led as sheep to slaughter.”9 This was the slogan that I recall from my school days in Israel in the 1980s, often repeated before the Holocaust Remembrance day. We were taught to be content to have a country of our own, so that we’ll never be the sheep again.

Oliver started to accompany me to the farm when I came to clean the wool. He could wander around the farm freely, join Bill in the wood workshop, help Lauren collect eggs from the hens, and—the absolute highlight—drive a tractor. Supervised by one of the adults, he almost single-handedly drove dirty water to dispose of, or shuffled things from place to place. For Oliver, the farm became the place to collect new memories, while I and people helping me were making a mattress for him to sleep on, stuffing it with memories of our own.

Sheared wool in a basin, 2020. In the photo: Wendy Wustenberg. Photo: Rotem Tamir.

Learning scouring together, 2020. In the photo from left to right: Martje Oostra, Wendy Wustenberg, Lauren Wustenberg. Photo: Rotem Tamir.

Scouring, 2020. In the photo: Martje Oostra. Photo: Wendy Wustenberg.

Wool drying on a rack, 2020. Photo: Rotem Tamir.

Order of Actions

To scour 250 pounds of wool:

- Place the wool in the basins.

- Boil the water for scouring.

- Connect the hot water pipe from the washing machine to the basins.

- First wash with cold water and dispose of the dirty water container with the tractor.

- Add special soap for wool.

- Wash again with hot water: fill with hot water until the wool is covered and then add boiling water.

- Leave the basins under several blankets for 30 minutes.

- Dispose of the dirty water.

- Wash with cold water.

- Repeat the process if necessary.

- Take the clean wool out to dry on the drying rakes. The drying takes several days.

- Once the wool is dry, the time comes to untangle and card it.

Liza, Again

When I lived in Lexington, I went to a therapist who helped me deal with anxiety. Her method was aimed at healing trauma. The beginning of the process was to recall something positive and calming, something to fall back on, in case a difficult moment needed to be overcome. Through this therapy I return to the living room of Aunty Liza, to the sofa that stood there, simple and comfortable like a single bed. She has just left the bathroom, wrapped in a long dress, she comes to the sofa to sit next to me, a towel and hair brush in her hands. Her hair is long, gray, and tangled. She brushes this long hair, undoes the knots, some gently, some forcefully. I watch her brushing and braiding her long, gray hair. I could see her doing that when she is 10, 20, 30 years old, a woman of beauty and power.

Carding

You can card the wool using two dense brushes (cards.) We used a simple carding machine, consisting of two drums covered with card clothing, a surface composed of thin metal rods. The smaller drum, the licker-in, feeds the fibers and straightens them against the larger storage drum, until it is completely full. The resulting layer of wool is removed and cut off, forming a long and thick sliver of aligned fibers. The first time I saw this long sliver I began to cry. I stroked the wool as if it was Liza’s hair, as if it was Wassi’s hair. For a second I felt the presence of the three sisters: Grannie Wassi, Aunty Liza and Aunty Esther.

Sumac, 2020. Photo: Rotem Tamir.

Harvesting sumac, 2020. Photo: Wendy Wustenberg

Preparing dye, 2020. Photo: Wendy Wustenberg.

Preparing dye, 2020. Photo: Wendy Wustenberg.

Dye sample, 2020. Photo: Wendy Wustenberg.

Sumac dyeing bath, 2020. Photo: Rotem Tamir.

Fabric dyed with madder, 2020. Photo: Wendy Wustenberg.

Drawing with natural dyes, 2020. Photo: Rotem Tamir.

Drawing stripes in the studio, 2020. Photo: Rotem Tamir.

Dyeing

Upon my arrival to Minnesota I was surprised to see the sumac shrubs growing along the roads. Sumac was familiar to me from Israel, and at first I wasn’t sure that it was indeed the same plant. I love the deep purple color of the spice and its lemony flavor, so I add it to every salad I make. When visiting Pipestone I asked Bud about sumac, and he told me that Native peoples use it for food, healing, and dyeing.

The artist Martje Oostra was interning in my studio during that time, fully engaged in scouring. Martje was knowledgeable about sustainable textile manufacturers and helped me a great deal when the time came to choose and order the mattress’s upholstery cloth. We went for a sturdy herringbone organic cotton, grown in Texas. I had the cloth; it was dye time.

Fall is the best season for sumac harvesting, so while wool scouring was slowly progressing, I went with Oliver to collect sumac fruits near his kindergarten. I cooked them in my kitchen and began experimenting with cloth dyeing, succeeding at delivering grayish purple shades. I was also fascinated with the deep red derived from the madder plant, a colorant used by many cultures across the globe, often referred to as “Turkish red.” I sent my mother the pictures of the dyed samples and she recalled the red color mentioned in the Bible in the decoration of the curtain that concealed the tabernacle in the temple of Solomon.10

Achieving the deep red hue is not an easy task. Many factors are at play, from water mineral components to differences in temperature. I was a novice to dyeing, so it was hardly a surprise when the recipe that brought about the deep red in my kitchen yielded a pale pink in a farm located 15 miles away. I contacted local textile artists and got a list of detailed instructions, yet looking at it, I realized that working intuitively will be more productive in my case.

By luck or by science, here was the cloth, dry, and it boasted a dark siena hue. I spread it on the studio floor to draw the stripes. They were to be drawn by hand, so that every oscillation of my body would be registered in the line. Sumac gave me the purplish stripe, buckthorn: the greenish yellow, cochineal: the vine. I attached a wide brush to a stick and walked along the cloth, drawing the stripes as I went. As promised, the stripes, though not completely straight, helped me sew the mattress together with a huge pile of wool laying between the back and the front cloths.

Stuffing, 2020. Photo: Rotem Tamir.

Stuffing, 2020. Photo: Rotem Tamir.

Stuffing, 2020. Photo: Rotem Tamir.

Tufting, 2020. Photo: Rotem Tamir.

Sewing, 2020. Photo: Rotem Tamir.

Mattress project: cloud diagram of people, places and crafts. Rotem Tamir, 2021.

Sewing

I had the stuffing and the cloth. But how does one make a mattress? How to sew? What threads to use? What stitches will hold the wool in place? How to join everything together and make it look uniform and beautiful? Both my dad and uncle Yacov tried to explain some things over the phone, but hands-on knowledge can only be demonstrated, not explained, so distant communication was of no use. Besides, they never really made a mattress, they only remembered one. Wendy came to my rescue by introducing me to an upholsterer, Larry Garner. He invited me to his workshop and together, using our joint experience and intuition, we succeeded in recreating the traditional technique of sewing and tufting. We spent the whole day making a small-scale model which I used in my studio later on to realize the full-scale piece. Working with Larry felt as if I was in uncle Baruch’s workshop. Larry was family—not in blood, but in craft.

When the mattress was ready, I sent pictures to my family. Astounded, uncle Yacov said that it looks exactly like the original mattresses. What’s more, in a conversation with my dad he revealed that the family of Grannie Wassi in Tripoli were all dyers—something that neither dad nor me were aware of.

Remembering is an activity

Remembering is like composing a collage, something partially imagined that one pulls together from the past. To pull up more fragments, I decided to talk with my dad’s siblings and find out if they remembered anything about the mattresses. All of them—Uncle Yacov, Aunt Hannah, Nisim (my dad), Uncle Emanuel and Uncle Amos—live in Israel.11 I first spoke with each of them individually, but then realized that I could organize a group conversation. They all loved the idea, all responded enthusiastically and brought in the younger generation to overcome the technological obstacles. We agreed on a date.

I know that the event was moving. I’ve seen the joy on the siblings’ faces when they saw each other. They talked and laughed and they wouldn’t stop. My hearing aid malfunctioned. I could hardly make anything out of the conversation. So no new insights on this front—though they all wrote to me after, saying how much they enjoyed talking all together and how rare this has become. They all want to do it again.

Translated from Hebrew by Katya Oicherman

Mattress ג’ראיה project was supported by: Windswept Hill Farm, Stove Works, University of Minnesota