Out of Place: Black Triage and its Afterlife

PhD candidate in geography and writer Aaron Mallory explores the space between injury and death to discuss the afterlife of triage.

To be black is to be injured. An injury is a status, a commonly held social belief that one is not in good health. What it means to be to healthy depends on your place. We only speak of health when things aren’t well.

To be injured is to move closer to death. Injury is a liminal space and time where life transitions towards death, modern medicine. We call it modern because those in power started to care about populations,1 their populations. Medicine develops not to prevent injury but to intervene in the space and time between injury and death. The longer an injury persists the shorter the liminal space between life and death becomes.

It is from the space and time between injury and death where the concept of triage emerges. Civil War doctors would make judgements, observational assessments based on severity of injury, or the amount of time one had before a suspected death. The triage was based in Antebellum medical science, perfected on Civil War battle fields but built from the living bodies of slaves. Slaves weren’t (A) Human but their (B) Human was enough to inform Antebellum doctors of the liminal space between life and death.2 The space of injury for a slave was expanded through “medical science” to understand the limit of (A) Human flesh. Yet, triage is a French word used by ambulance companies to standardize a nation through the sorting of what was proper and good.3 Although the measurements made from slaves’ bodies never met the goodness of fit for the French man, the standardizing of a national body, the literal parameters of which a French body should take, was built against the body of (B) Human.4 We remember her as Sara Baartman.5 The black body coheres our understanding of injury as the space and time between death. This body functions as a hieroglyphics of the flesh6, where injury is known because black bodies occupy that liminal space and time as we inch closer to death. Triage is a measurement of black bodies injured in space.

It is space and time, the place between premeditated death and instinctual survival that claims are made against black lives. Was Darren Wilson encountering a demon? Was George Zimmerman losing the fight? The case for each hinged on a narrow space and time compression where intent could neither be proven or jeopardized. The case made against the life of black boys that were formally living, were decided against another space and time dynamic that measured their intent. Did Mike Brown commit a crime? Was Trayvon Martin walking out of place? The space and time of their encounter extend beyond the limited space and time that was offered to their killers. The difference between murderer and suspect were years. And like Trayvon, Oscar, and Mike, Renisha’s case, a case for black life, came down to the space and time of intent reflected through the space between injury and death.

The afterlife of injury

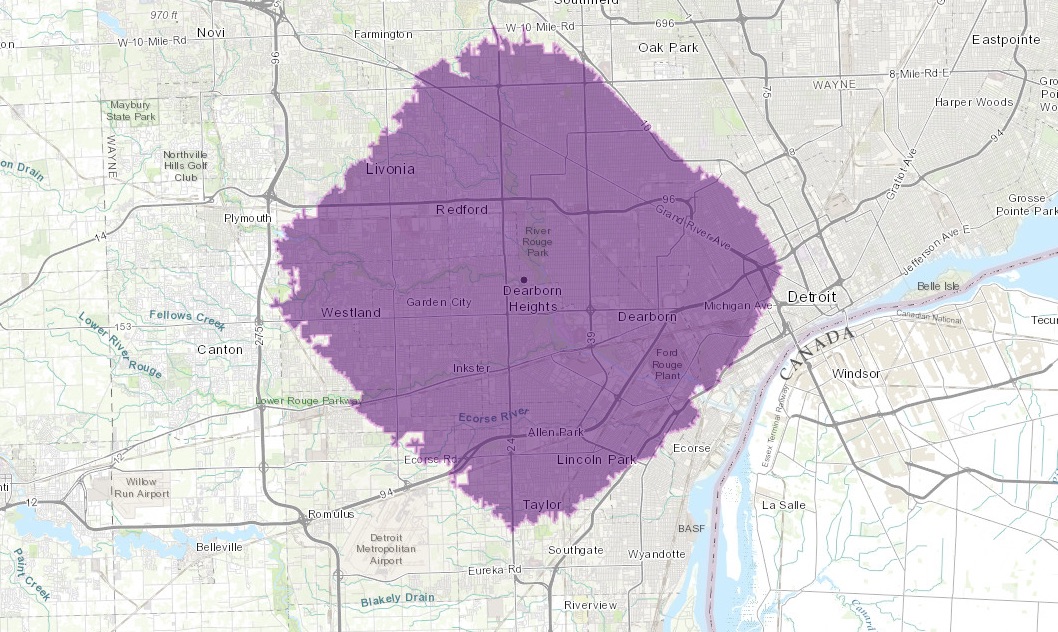

Dearborn Height’s Police received multiple calls about a car crash in the night. The police deemed this to be a low priority and arrived 30 minutes late with emergency medical services. They inspect the scene, retrieved the broken car, and went back to the station. No search, no call for help was made to find the operator of the vehicle. They knew that the driver had left the scene. Was it a crime? Or a common occurrence for a (white) community so close to Detroit. The driver had a name, Renisha. The police didn’t name her. Renisha goes into the night without any official record. What is known is that she encounters a killer in the night. The case would go to trial and the killer in his defense said “he feared for his life.” And like other black lives previously, the defense is set into a narrow space and time of intent. Was he afraid?

McBride was absent for three hours.7 The low priority of the police triage meant she was never looked for. Geography is the study of pointing out what is there in relation to other things.8 Without a search or formal inquiry, McBride is without geography, without place. McBride is everywhere and nowhere without coordinates. She wasn’t missing because to be missing the state, or police in this case, has to recognize that one is out of place. For black bodies, black women, their legacy is to be out of place in the non-coordinates of households, sheets, and white femininity. Being out of place allows black women to be called by many names, if it weren’t for names, society would make them up.9 With no name in the street, it’s rare people don’t victimize.10 Black women are in a suspended state, ebbing and flowing between injury and death.

What happens to the afterlife of injury? What if the space and time between injury and death is too much to bear with the living? What if being out of place impacts living geographies? Those 3 hours of time punctuated by the inaudible but present words, “I want to go home” followed Renisha’s afterlife.11 It’s because of this that we see a victory, a real victory of sorts. When the movement for black lives faces no justice, failed justice, time and time again, there was a victory.

Whatever limited victory that a top-down hierarchically driven criminal justice system could give, people (family, community, a nation) got. Although (black) bodies never come back whole from the other side, they contain an afterlife. The afterlife of the here and now is punctuated with the names of those who have transitioned. As long as we speak their names, speak truth to their experiences, in return, we (black people) get hope. When we forget names, we forget black bodies.

We forget black bodies when the official cause of death, in New Orleans, for example, is labeled an accident rather than officer homicide.12 We forget black bodies when police tattoo smoke on their skin for every person they’ve killed.13 We forget black bodies when we build on top of the final resting place of former convict farmers who extended the plantation economy into the present.14 We forget black bodies when we label them “at risk”. We all know the risk of living while black but it’s our names and the communities that hold us beyond risk, injury. If something should go wrong, you will always be remembered. Renisha.

This article was commissioned and developed by Mn Artists guest editor Chaun Webster as part of the series Blackness and the Not-Yet-Finished.