Notebook: Now, Here

Writer, public artist, and cultural organizer Shanai Matteson ponders the slow work of relationships, the language of social practice, the threat of extraction, and the consequences of drawing boundaries, in the first of two dispatches from the pathway of the Enbridge Line 3 oil pipeline.

When Matthew Fluharty invited me to contribute a piece to his series Towards a Local Practice, sharing my experience as a public artist who has lived and worked in both rural and urban places, I was nervously awaiting a decision by the State of Minnesota Public Utilities Commission (PUC) on the fate of a new oil pipeline. There are many reasons I oppose Line 3, and among them, the fact that this pipeline would transect the place that I come from in northern Minnesota, putting land, water, and people at risk.

The decision whether or not to permit Enbridge to build a new oil pipeline was finally made at the end of June. Against the testimony of impacted tribal communities, evidence from climate change experts, as well as opposing comments by thousands of Minnesota residents, the appointed Commissioners of the PUC agreed that Line 3 needs to be built. As permitted, it will follow the “preferred route” of this Canadian corporation, which will profit from the movement of oil through our communities.

While I want to focus on what this development means for my own understanding of local practice, first I have to take a moment to reorient myself, and not just in place—but also in time. I can no longer speak about my artistic work as though it is separate from who I am, the places and experiences I come from, or the time in which I’m living.

Four years ago, I attended a symposium on social practice art at the Plains Art Museum in Fargo, North Dakota. Those who attended Central Time Centric might recall what transpired on the final day of that gathering.

It was the height of the Bakken Oil Boom, and many people across the northern plains were grappling with ways that the extraction and movement of oil was wreaking havoc on landscapes, economies, and cultures. Just few years later, water protectors at Standing Rock would make international headlines, bringing the impact of oil extraction and infrastructure on indigenous people to the forefront of conversations about the future of energy, environment, and activism.

But at the time that we gathered in Fargo to talk about social practice art, Standing Rock had not happened yet, and many of us were still ignorant of the ongoing impacts extraction was having on indigenous people and communities. We were ignorant about what was happening now, because we were not considering what had historically been happening here.

While we were gathering for an arts conference in Fargo, people were also gathering in Ferguson, Missouri, to protest the killing of Michael Brown by police. Michael Brown’s tragic murder, and the murders and protests that followed, sparked a nationwide awakening to the ongoing violence and oppression that black and brown people face all across America.

There was a moment during what would become the final session of Central Time Centric, when the relationship between these lived realities of oppression and violence, and an art world that allows some artists to benefit while maintaining a critical distance from both their subjects and their subjectivity—became newly apparent to some, but was all too familiar to others.

When a white artist on a panel was confronted about the exploitive nature of his public art, and the colonial language he used to describe the local communities he was working within, some of the most urgent questions about the role of socially-engaged artists (and in particular, those working in communities to which they do not belong) rose abruptly to the surface.

What were we really doing there? Or here? Then? Or now?

Did we really know the places, and the people, with whom we claimed to be working? Were we committed to their well-being, or were we just advancing our own artistic careers? Were we willing to be honest about ourselves—our assumptions, our ignorance, our motivations? Were we prepared to reckon with our complicity in oppressive economic systems?

I wrote about my experience at Central Time Centric directly afterward, and in the years since that gathering, have continued to return to the questions it provoked.

I return often to questions about what happens when we define an artistic field and its vanguard, for example: social practice, placemaking, or rural arts. How do efforts by practitioners, funders, and critics to define these fields change the very nature of the work? Why is it important to pay attention to the ways language about artists and their work draws boundaries? What do we miss when we focus on individual projects and practices, instead of the critical (and long-term) work of building and sustaining relationships?

I also return frequently to questions about what it means to belong—to a place, a time, a social movement—and why belonging matters to artists, for our work as artists living and working with place. How do we locate ourselves and define our work within the very landscapes, economies, and cultures many are struggling to resist? Should we define ourselves primarily by our artistic work, or are there other ways to imagine the role of artists in community?

And what about those who are struggling to survive in this economy, while some of us earn a living as professional art workers? Will there come a time when none of us can claim a critical distance from these issues?

There are two questions that I will always hesitate to answer:

What do you do?

Where are you from?

It’s not that I don’t have answers.

I am an artist. A writer. A mother. A believer in us.

I am from a small town. A big family. A rural place.

I am from a poor, white, rural place.

It was not always a white place.

It is still not only a white place.

If there is any measure of my success in this lifetime, it will be my ability to continue refusing a straight answer, in part because that answer necessarily changes with the nature of the person asking the question. And because I believe in creating a life by continually revisiting questions over time, pushing against the edges of what are assumed to be the only way to live out our answers.

I remember in Fargo, taking a walk to dinner with Matthew Fluharty and a dozen others. As a small group, we had gathered around our shared passion for creative work that tends to land and water. Many of us also happened to be from rural places.

Matt had introduced a term at the symposium that I’d never heard before: rural diaspora. He explained this as the idea that those of us from rural places—even those who have left those places—identify with something about rural landscapes and cultures that isn’t readily apparent to others. That our experiences within those landscapes defines some critical aspect of who we are and how we work.

But what is it?

And what is it not?

On our way to dinner in Fargo, we waited to cross the railroad tracks while yet another oil train rolled past. It stretched beyond our field of vision, and I found myself thinking about my hometown in northern Minnesota.

Back in 2014, plans were already underway to build an oil pipeline across the Mississippi headwaters called Sandpiper. It would move oil from the northern plains through the place where I’d grown up, a small town called Palisade with a population of just over 100 people. If built as proposed, this oil pipeline would have crossed the Mississippi River less than a mile from where I learned how to swim.

While Sandpiper was delayed, and then denied, the proposal resurfaced as Line 3—which Enbridge now claimed was a replacement for an existing oil pipeline they had allowed to fall into severe disrepair. It had already ruptured in 1991, causing the largest inland oil spill in the United States just outside of Grand Rapids, Minnesota.

The preferred route that was chosen for the new Line 3 was nearly the same as Sandpiper. It avoided direct crossing of reservation lands, making a jog south through a part of Minnesota that is sparsely populated, economically depressed, and where land is relatively undeveloped.

This makes the place I come from a fantastic habitat for all kinds of wildlife, and has helped to preserve the quality of water both above and below ground. These things—in particular, the economic hardship many residents face—also make this area a magnet for extractive, exploitive corporations looking to site infrastructure projects that are high risk and low-benefit.

The thinking goes: When people are desperate for jobs and can’t imagine a different future than the one before them, almost any kind of development will do, and political resistance is not likely to be an issue.

Even in 2014, before I’d realized many of the things that are now central to my sense of who I am and what I do, it was hard to sit at an art conference listening to others speak about their professional roles as social practice artists or arts leaders as though art were just another career option or economic development tool.

I was sitting there, trying to imagine a radically different future, one in which there are a multitude of creative ways to stop (or at least slow) the extractive, exploitive economic development that was proposed (often) in a place I love. And I was realizing quickly that this isn’t a task that a single community, let alone an individual artist, can address on their own. We could barely wrap our heads around the changes we were already witnessing in our communities, and everywhere.

When I thought about what was happening in Fargo and Ferguson, and what was going to happen in my community too (and many others) if corporations continued to have their way, I wanted to rage at the language being used by my peers to talk about their projects.

Singular projects seemed too small, too short-sighted, and too individualistic. The goals being set by artists and arts organizations seemed too naive or blind to reality, and too dependent on timelines and frameworks that had been failing our most vulnerable communities.

To me, there’s a difference between working on projects, and developing a sense of myself and the collective power of our relationships and culture over time. Too often, when I’ve thought in terms of projects or my own creative practice, I’ve found myself thinking and working on timelines that don’t actually make sense to the task at hand.

What is one year, or two, or even five—when what we’re really talking about is the urgency of ending extraction and healing the land—for the survival of our species? It’s as though we assume that if we can just extract enough culture, and use it to fuel our own ideas of short-term progress, that will be enough.

At times, I have used the language and framework of projects to communicate what I’m trying to do right now, with those who define the field. I recognize that to define the field is to set the conditions within which we’re often expected to work, as artists or arts organizations (even independent of them). Some call these people thought leaders. Often, they function as gatekeepers.

So now, when I speak in the ways I’m expected to speak about my artistic work, I am always thinking generations ahead and behind me. What other worlds are possible, and how do we work now to bring them to life, over time?

No one ever asks Violet Spolarich where she is from, or what she does for a living.

My grandmother has lived on the banks of the Willow River in Palisade her entire life. If you stop to visit her in the small log house where she lives today, she will invite you to sit down at her kitchen table. She will offer you bread that she’s just baked, and if you care to know where you are, you’d be a fool to turn it down.

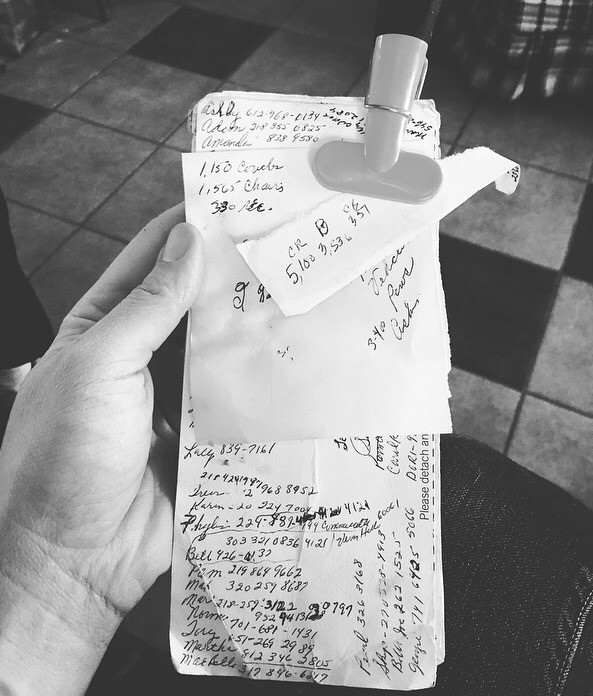

My grandmother keeps a tally on her refrigerator, scribbled onto the backsides of cereal boxes and used envelopes. These lists contain a numerical record of all of the things she’s had a hand in creating over her eighty-six years on this river:

Seven children raised.

A few dozen grandkids.

1,150 couches upholstered, plus 1,565 chairs.

330 boat seats for the cabin people.

5,100 cinnamon rolls and 3,536 buns, all given away for free to people she meets.

A manila folder of poems, most of them about her family, or the river she loves.

A clothespin bursting with clippings from the local newspaper, opinion letters she’s written.

I first learned about Enbridge and their oil pipeline from a letter my grandmother wrote to the local newspaper. My grandmother frequently speaks out against exploitive economic development, because she knows these projects will put her place and her people at risk, without doing much to change life for the better.

Unfortunately for all of us, those kinds of developments keep coming, and my grandmother is not getting any younger.

Is Violet Spolarich a social practice artist? A rural artist?

If you ask her a question like this, I guarantee she will avoid a straight answer. Instead, she will offer you another plate of cinnamon rolls and a story.

Perhaps it will be a story about the time she and her neighbors stopped a garbage burner from being built on the banks of the Mississippi River. They did this, she will tell you, by writing letters and poems, and publishing their words in the local newspaper.

They also did this by showing up, together. By gathering again and again to speak the truth of their stories and their love for the place that has sustained them. To speak, as well, about what other futures they imagine for that place.

Who is listening?

Recently, I brought some new friends to visit with my grandmother.

As pipeline activists, they were there because they understand that when Enbridge starts building Line 3 across northern Minnesota, communities like the one I’m from could be critical to the success or failure of efforts to stop it, or to lessen the impacts.

Rural people like my grandmother could support the resistance movements led by indigenous water protectors, climate activists, and environmental leaders. Many already do. And, people living in communities like the one I come from might empathize with Enbridge, believing in their vision of the future—one in which oil is still worth more than water, and pipelines never leak.

They could rally to protect the place where they live, or just as easily decide to assist the network of law enforcement already strategizing to stop popular protests. That’s the thing about the moment we’re in, no one knows what will happen — but we do know that whatever happens, will happen at the scale of our trust and our relationships.

Including our relationships to our places.

That afternoon, while we sat at her kitchen table, nervously awaiting the decision of our Public Utilities Commission, my grandmother told us about the day Enbridge came to survey for their oil pipeline.

She said she knew who they were the moment their truck pulled in, because people from around here don’t drive trucks like that, or look at the land with such impatient eyes. And because she’d heard from someone up the road—someone she trusts—that company men were coming with another round of promises.

First they came to look at the land, but not too closely. After all, they had their maps, and so they didn’t need to know what the land meant to those whose stories were entangled with the pines, the swamps, or the rivers, the very people whose lives now depended upon those ecosystems staying intact. Next, they offered to lease easements from farmers and others, saying that their pipelines were safe and sound, and absolutely necessary.

My grandmother knew she didn’t have anything to sell to Enbridge, or anyone else, so she did what she always does: She offered them a chair and a plate of sweet rolls. She invited them to look around awhile.

As they did, she took note of a few things others might have missed. As soon as they left, she started writing.

This piece was commissioned and developed as part of a series by guest editor Matthew Fluharty.