Together in the Dark

At a screening of experimental films at the Minneapolis/St. Paul International Film Festival, things go wrong in fascinating ways.

In April of 2017, Cellular Cinema curated two screenings of short experimental films and videos for the Minneapolis St. Paul International Film Festival (MSPIFF). It was our second year of participation in the festival – in 2016 we created an elaborate series of events, including a full day’s lineup of hour-long programs by guest artists in an adjoining space, in addition to two short programs.

Though we don’t necessarily need MSPIFF as a venue to screen work, and their overall involvement is minimal beyond including us in the program, we wanted to remain engaged with the festival to some degree, partly because we like the people in who run it, and we want to continue to include experimental film and video in the ongoing cinematic conversation in the Twin Cities, however we can.

Part of what we have to offer the festival which is unique, and grows more unique every year, is that we remain interested in showing work on film. Many experimental filmmakers still regularly shoot 16mm and Super-8 that mainstream independent filmmakers have definitively abandoned, and some of them are interested in sharing their work via film prints as well. So, part of the deal is that we bring our own 16mm projectors and projectionists into the theater space, projecting from tall stands in the back of the auditorium.

I’m not always picky about definitions of film vs. video vs. media vs. cinema, but it’s interesting to me that, outside of our screenings, there is no actual film left in this Film Festival, or in practically any other film festival, locally or internationally. The “print” traffic of the festival consists almost entirely of hard drives with DCP-encoded files; the festival official in charge of “print” traffic, when we first worked with him in 2016, had not actually encountered a film print in years.

This fact only bugs me when the iconography of these festivals is still preoccupied with what are very clearly film projectors, film cameras, and film prints – with sprocket holes and individual frames, big round Mickey Mouse ears of film spools… it seems disingenuous to me somehow, when practically every moving image circulating through these festivals is an algorithmically compressed digital file on hard drive, that festivals should still benefit from received, romantic, and nostalgic connotations of clickety-clackety projectors and the good old days.

At any rate, the fact that we project film on film is still a selling point for some audience members. I have an incredibly short attention span for debating the merits of analog film versus the digital moving image, beyond a blanket statement that feels pretty inarguable to me: film and video are different. Neither is better, nor worse; they are merely different, in the way that an acoustic guitar is different from an electric guitar to a musician, and that watercolor is different from oil is different from acrylic to a painter, and wood is different from metal or clay to a sculptor.

In 2017, MSPIFF has foregone sprocket holes and celluloid in its marketing and branding — thankfully in my opinion — but apparently at a loss for any other ideas representative of iconography of Contemporary Cinema, festival organizers chose… blue and yellow fabric, light and translucent, floating against a white background. I have no idea what this means or what it has to do with cinema, but it’s pretty, I guess.

We had a pretty sizeable crowd for our first screening — maybe 80 people. The program consisted of 12 short pieces, some local, some filmmakers from far away. Some of the pieces were shot on film and projected digitally, some were purely digital, and some were shot on film and presented on film, by our own projectionists. The sound for these 16mm works was wired to run into the projection booth and through the house speakers.

The first film was 16mm transferred to digital, the second was a non-narrative digital experimental piece, and the third film in the lineup was our first film projected on film. This last one had accompanying sound as a digital file, which would go from the projectionist’s phone, into a small mixing board, and back into the projection booth, where it was patched into the theater’s speakers.

The previous piece ended and the screen went dark – digital dark first, with light from the projector still visible as near-black pixels, then that too was doused and we were in complete darkness together. I was standing at the back of the theater next to the projectionist, who was the author of the next film as well. I soon became aware of him softly cursing to himself, and after a few moments, he hurried out the back door of the theater to consult with the projectionist in the booth. When he came back, I learned that there was a problem with the sound, which wasn’t playing through to the house speakers as expected.

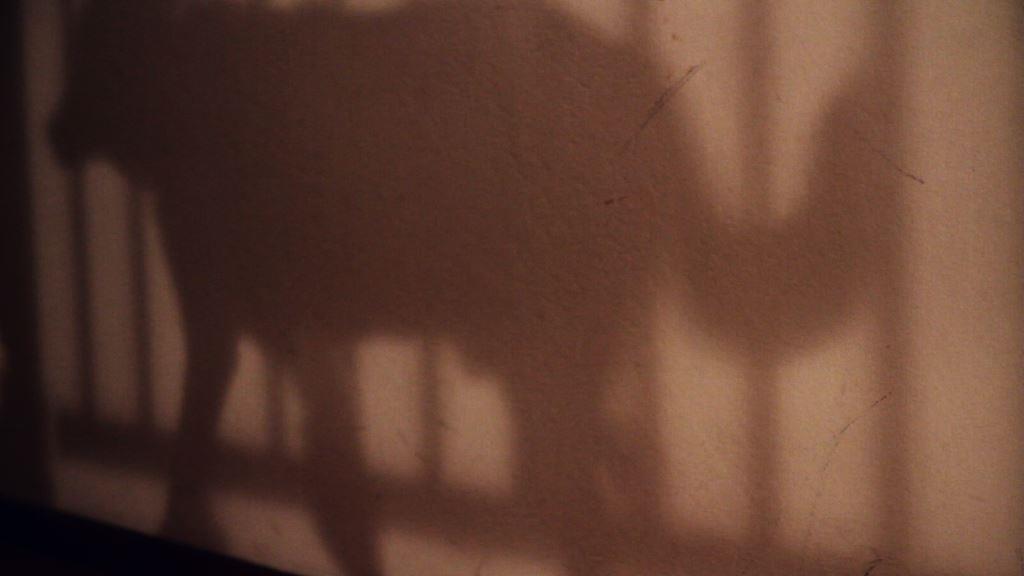

The mood in the dark theater shifted quickly. Within a minute, when it became clear that something wasn’t going as planned, someone in the middle of the audience swiftly pulled out their phone, turned on the flashlight function, and began making shadow puppets on the screen. After that episode, another audience member near the front pulled out their phone and waved it around in the air, creating their own light show. One or two polite “no thank yous” were heard from other audience members, and that was the end of the impromptu phone-light performances.

The mood in the dark theater shifted quickly. Within a minute, when it became clear that something wasn’t going as planned, someone in the middle of the audience swiftly pulled out their phone, turned on the flashlight function, and began making shadow puppets on the screen.

After a few more moments of waiting, as a co-host of the screening, I made a semi-authoritative comment to the group about technical difficulties, but for the most part, I just left people to their own devices, literally, while I experienced a few moments of anxiety about the screening, interspersed with an anthropological fascination with what was unfolding before me.

A few people, including Al Milgrom, former festival director, simply left. Many others pulled out their phones to do phone things, or to consult the festival program by the light of their screens. Others, I suppose, chatted amongst themselves. And some of us probably just sat quietly, listening to the murmuring of the crowd, or daydreaming. Within minutes, the problem was solved and the screening was underway again. Everything else went smoothly, though I certainly held my breath a little bit during every subsequent transition between the analog and the digital for the remainder of the program.

Many of the films in the program were, in my opinion, excellent. But what really sticks with me about the night is that first uncertain pause, and how we reacted to it as an audience. During the Q&A after the screening, I wanted to make a comment about John Cage’s piece 4’33, where a pianist sits silently at the piano for four-and-a-half minutes, and the avant-garde sound composition results from the rustling and coughing of the audience in the hall. But I couldn’t find the right moment, and I was self-conscious about sounding like a pretentious art professor.

In the almost three years that Cellular Cinema has been hosting screenings of experimental film, video, and expanded performance, I’ve grown really used to a certain informality of presentation, and a roughness of transitions from one piece to the next. I often let the audience know in advance that we’ll be sitting in the dark together for a minute or two between films, as a projector is threaded or moved into place. I haven’t spent a lot of time recently in the world of seamless digital transitions that is the modern movie theater.

I remember screenings, not terribly long ago, at the late Oak Street Cinema, which along with the Bell Auditorium, used to be the home of the U Film Society, run by Al Milgrom, which at some point became the MSP Film Society, the organization which runs the festival. I remember showing up for screenings of extremely pink, faded, dirty repertory film prints, full of breaks and splices, sometimes requiring whole chunks of the film (still only a few frames long) to be cut out, the theater lights coming up, along with some vague knowledge that triage was being performed by an expert, sweating projectionist above us, behind the window to the booth.

Some of the projectionists at the Oak Street were friends of mine, so I occasionally got to visit the booth. It was a wonderful, well-used, shabby space containing a deep-sagging couch with torn upholstery, a desk, and a workbench in a room adjoining the solid steel, industrial projectors.

During those moments of anxiety during our MSPIFF screening, I poked my head briefly into the booth, and was taken aback. In the intervening decade, it had become a strictly utilitarian space: an unfurnished closet with gray cinderblock walls, housing two humming digital projectors, each with a rack of hardware for sound, and a single screen and keyboard interface which cast a faint blue light through the space.

The booth is no longer a place for humans to inhabit for more than a few minutes and mouse-clicks, perhaps to select the trailers to show before a particular film. Everything else is now automated and set in motion remotely.

The festival projectionist, Randall, seemed thoroughly competent, and I was grateful that he was patient with me as I checked in with him anxiously a few more times during the screening. He was able to work with us to sort things out, so that everything played as expected, with only that single short interval of discomfort and uncertainty between films two and three. In the theater that night, we got to experience the rare art-adventure of not knowing what would happen next. And we got through it. I can be as compulsive as anyone with my own small screens, but I’m grateful that there are at least a few spaces left in my life where those devices are, if not outright prohibited, at least strenuously discouraged.

I don’t believe that a work of art must be challenging, or that it must make me uncomfortable, to be serious or legitimate. However, in a world that is increasingly, algorithmically geared toward a steady stream of soothing distraction, I’m glad that at least some of my art experiences remain messy and imperfect, and require the mediation of actual breathing human beings.

Fortunately, for anyone who needed one, the safety blankets of our own small screens were near at hand to comfort and occupy us, to bridge those few troubling and increasingly uncharacteristic minutes that we spent, truly and literally, though briefly and safely, together in the dark.