The Believing Game

Filmmaker and educator Kevin Obsatz on art experiments, the freedom in making "unmarketable" work, exercises in belief, and practicing porousness in an impermeable age.

In the believing game we return to Tertullian’s original formulation: credo ut intelligam: I believe in order to understand. We are trying to find not errors but truths, and for this it helps to believe. […]

To do this you must make, not an act of self-extrication, but an act of self-insertion, self-involvement—an act of projection. And similarly, you are helped in this process, not by making logical transformations of the assertion, but by making metaphorical extensions, analogies, associations.

Peter Elbow, The Doubting Game and the Believing Game—An Analysis of the Intellectual Enterprise

What the beyond of teaching is really about is not finishing oneself, not passing, not completing; it’s about allowing subjectivity to be unlawfully overcome by others, a radical passion and passivity such that one becomes unfit for subjection, because one does not possess the kind of agency that can hold the regulatory forces of subjecthood […] It is not so much the teaching as it is the prophecy in the organization of the act of teaching.

Stefano Harney & Fred Moten, The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study

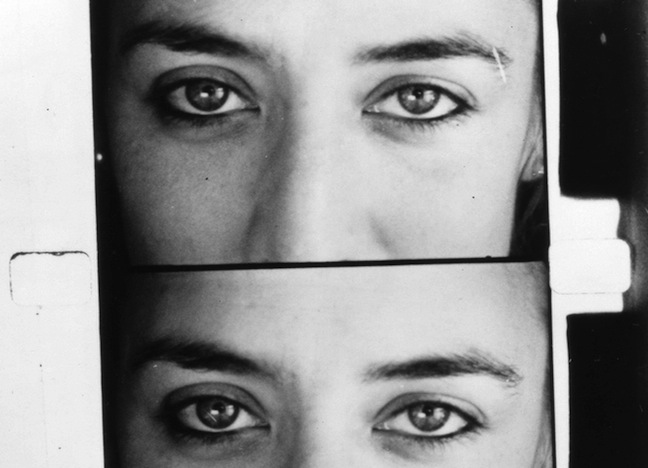

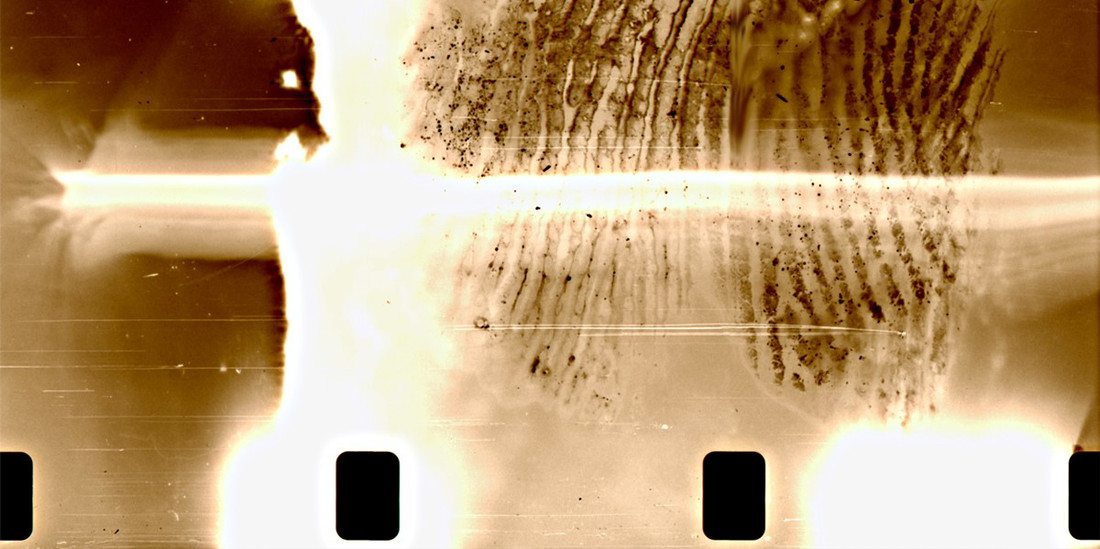

I first met Pip at the Cannes Film Festival, when I was there as a student intern in May of 2000. He had, and probably still has, some kind of inscrutable relationship with the American Pavilion Student Program. Pip’s father was a New York filmmaker, I heard once, who was blacklisted during the McCarthy Era, so Pip had been coming to the festival since he was a kid and was friendly with many of the thick, older security guards. In the midst of a seminar day full of advice about selling screenplays and self-marketing, Pip projected some of his own scratched, hand-developed super-8 films, explaining that he had processed them roughly to evoke the turmoil of his failed relationships and complex feelings about Paris, where he lived. One of my vivid memories from that year is hearing some of the more career-oriented interns, who must have been French, try to engage with him about movies that were part of the Official Selection that year – Pedro Almodovar, or Olivier Assayas… ”ca ne m’interesse pas” he kept saying: “that doesn’t interest me.”

The following year, I was living in Paris with my girlfriend, who was studying at the Sorbonne. I didn’t know anyone at all, so I contacted Pip, who was more than willing to invite me to a bunch of experimental film screenings around the city. Paris is full of tiny, basement-level theaters that show international and repertory films—microcinemas before there was a word for it. So, it must have been fairly easy to commandeer a 40-seat theater from time to time for an experimental film festival.

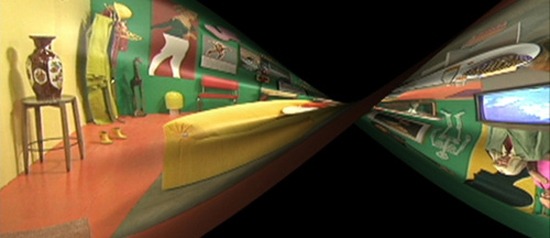

Tony Conrad was a special guest at one screening – he’s in all the textbooks for his “Flicker Films,” alternating clear and black frames of film stroboscopically. He played minimalist violin compositions – one or two notes in alternation – along with his work. Another time, Michael Snow came for a screening, one more grey eminence of experimental video history. The new work he shared was called Corpus Callosum, a 92-minute feature – I remember it as a slow, repeated dolly move across an office space, while an ambient sort of office scene played out again and again, with minor variations.

There were also, over the course of a year, dozens and dozens of shorter pieces, video and film, a few of which I found beautiful, but many of which were, in my opinion, tedious, poorly filmed and edited, and in some cases, downright appalling to my tender, 23-year-old sensibilities. One standout was an endless sequence of close-ups of a woman inserting test tubes in her vagina; the filmmaker was present for that one, and bowed for applause afterwards. I also have a vivid memory of what I think was a Vito Acconci video, originally intended as a gallery installation, featuring him with a raw cow’s tongue in his mouth, mumbling around it, for way, way too long.

I kept showing up for these screenings, partly because I liked Pip and appreciated having some kind of connection in the lonely foreign city, but also partly, I think, because I just didn’t get it. These people saw something in these films that I didn’t see, and rather than dismiss them and their art form, it made me curious.

Pip’s words at Cannes stuck with me, too – there is something profound and perverse about showing up to the most glamorous film festival in the world, year after year, and being sincerely uninterested in almost all of the feature-length, narrative, international art-house films being shown there. He wasn’t seeking attention for his stance, but if you did notice him, he became significant – the only guy there, it seemed, who didn’t at least pretend to believe the hype. Like Bartelby the Scrivener in the Melville story, he was somehow able to call the entire edifice of the festival into question just by refusing to be moved by it.

The following year I returned to Minneapolis and resumed my narrative filmmaking pursuits. I made a few films, got into a few festivals, but my experience in Paris was still working on me, deep down, like a slowly progressing but irreversible chemical reaction. Having experienced Cannes up close, and the churning film market there, I had seen the hypothetical, best-case scenario for the endpoint of any project I could complete in my lifetime. Make a good movie, get it into the festival, win an award maybe… and, go home and try to do it again.

At the heart of the art film world, it appeared to me, was the exact same entrepreneurial hustle that one would find in the mainstream film world, only with less job security and money. If the medium was the message, the message was a product to be manufactured as cheaply as possible and sold to a distributor by any means necessary.

Back home in Minneapolis I felt pretty lost. I spent a few years working in coffeeshops and as a security guard, making a little money as a videographer and editor-for-hire. There is no money in experimental film, and very little glory, besides – that much is clear at the outset. So, the experimental filmmakers I know do just about anything else to actually pay the bills, including especially teaching, but also a wide range of corporate gigs, temp jobs, and nonprofit admin-type things.

It’s a small enough community, with limited enough resources, that no one seems to be trying to make money off of experimental filmmakers either, which is a blessing. So, unlike “independent” filmmakers, who seem to be able to fundraise, kickstart, and trust-fund their way through the feature film production process, experimental filmmakers make do with an occasional project grant or teaching sabbatical.

Since there’s no hope of actual profit, and no high-profile awards ceremonies that I know of, there’s no “objective” way to evaluate the quality of experimental films, no way to rank them against one another. In addition, the wide range of available tools and techniques used to create experimental film and video makes their appreciation about as subjective as any experience I know of. All the possible metrics that could be used to professionalize the world of experimental film go out the window. It is, in a word, unmarketable.

This, to me, is a beautiful thing.

I started making non-narrative experimental videos in the context of a video blog, where I could put work and happily not care whether anyone ever found and watched it. I progressed, from there, to holding my own screenings, when I would finish a film, decide to share it, and invite other art friends to include something in the program as well. I received a grant in 2008 to attend a workshop at the Handmade Film Institute in Colorado, where I learned to hand-process 16mm film in buckets.It was as unpredictable and cumbersome a process as I could have hoped for, putting me, I felt, as far away as I could possibly get from commercial viability.

Then, a funny thing happened: I got into the MFA program in the Art department at the University of Minnesota, a fully funded program, and I was invited to teach an introductory course on Experimental Media.

The art department, anywhere in the context of a public university, is a strange beast indeed. At the U of M, it is situated within the College of Liberal Arts, which is itself one school among at least a dozen, including departments focused on subjects like Mechanical Engineering, Business, and Public Administration. Especially in the University today, where pervasive neoliberal pressures have intensified the focus on metrics, outcomes, employability, (i.e. bang-for-your-student-loan-buck), I think the art department is downright dangerous.

I probably shouldn’t be telling you this.

I got myself into minor trouble early on as a grad student, taking courses in the Cultural Studies department, because, I suspect, I was far too willing to believe everything I was reading. A text would be assigned, and I would dig into it, and the professor would inevitably expect some sort of critical response. Meanwhile, I would simply be full of appreciation for the new ideas I encountered. While reading Foucault, for example, I was fully willing to believe Foucault, to enthusiastically inhabit the world he was describing. Foucault was right, so right, about all of it. Heideigger, Bachelard, Baudrillard, Benjamin – I believed them all, and I couldn’t have been less interested in seeking out contradictions, dissecting their ideas to figure out who was the most right, or wrong, about what.

Teaching has been a delight. The only part that I struggle with is the grading and evaluation. Some students are so relieved just to try something different, to have an opportunity to experiment in a low-stakes environment, that they happily charge ahead in whatever direction they choose. But others continually ask me, all semester long, how I am evaluating them, how they are doing, pre-emptively apologizing for work that they think isn’t good enough, and nervous that a harsh grade could fall upon them at any moment.

I watch them learn. Their work gets better and more complex; they try new things and grow more comfortable with the tools of media-making, with the process of shaping visual images and sound to convey ideas and emotions. But particularly given that some are freshmen and some seniors, some art majors and some environmental scientists, the idea that everyone should experience similar “outcomes” is bizarre to me. I find myself extremely resistant to applying any sort of ostensibly objective measure to their performance or ability.

The Art department is not strictly “academic” – we have the Art History department and Cultural Studies for that. But neither is it a technical program, focused primarily on the utilitarian skills of becoming a good illustrator-for-hire or a sound effects engineer. The main thing I have to offer the non-art students, I have found, is the idea of the “art experiment.” Art experiments are different than science experiments. In science, you create a hypothesis and then fashion a highly controlled scenario with only one variable; then you execute the experiment to prove or disprove the hypothesis. An art experiment, by contrast, is (by my definition) the simple act of entering into a project without knowing in advance what the outcome will be.

Commercial filmmaking is usually as controlled as possible – variables are the enemy. Studio filmmaking runs on a relatively straightforward corporate industrial model, and independent film is its neoliberal stepchild: there is an investment in a startup business venture (a film production), which may or may not yield profit (a distribution deal, and ultimately ticket sales).

The art experiment, by contrast, is wide open and amorphous, and can grow in any direction you or it chooses. To a good percentage of my students, this prospect is completely novel, unheard of.

The goal of the art experiment is not to find the best answer or the right answer – it’s a way to practice being porous and generous, letting go of control, and opening oneself to new ways of perceiving and believing.

The Art department, within the College of Liberal Arts, within the University of Minnesota (Twin Cities Campus) is, we’re told in departmental meetings, supposed to be focusing on “outcomes” – demonstrable, quantifiable skills gained and concrete, tangible knowledge acquired at the end of each class, leading to an employable graduate who can pay off his or her students loans. It seems unacceptable to say, out loud, that the goal of the art department is not to prepare students for career success and economic prosperity. But what if that’s not actually what we do? What if what we do is more important than that?

At the heart of this focus on outcomes and professionalization in the liberal arts, seems to me to be a very specific ideological orientation toward the entrepreneurial subject. Just like in a sentence, the subject is a noun, a self, that takes action in the world (the verb) towards and around objects (homes, cars, iPads). An entrepreneurial subject, a Bachelor of the Arts, goes out and makes it happen, acts upon the world, finds a way to be a productive self within it.

The value of a liberal arts education is often described as the ability to locate oneself within the context of history, knowledge, and culture. This seems like a direct result of Enlightenment thinking, and a question of perspective: when I look out on the world, what is my perspective on it? Where am I looking from? How do things line up in a way that makes sense to me?

But the art experiment calls all of this into question, in the sense that it asks students not merely to consider different points of view, but different ways of seeing. “A radical passion and passivity,” in the words of Harney and Moten – a willingness to practice believing in something profoundly unfamiliar, destabilizing, even de-subjectifying.

The goal of the art experiment is not to find the best answer or the right answer – it’s a way to practice being porous and generous, letting go of control, and opening oneself to new ways of perceiving and believing. When my class is really humming, we’ll watch 20 different short works in a row, one by each student. And every piece will be profoundly different than every other piece, not merely in content or in style, but in its relationship to moving images and sound, at a much more fundamental level.

I have been surprised to discover, in my years of both making art and teaching, that a common reaction to challenging media art is anger, even rage. An audience member will see something new and not just dislike it; they’ll actively hate it. They’ll hate the film, the filmmaker, and, on some level, me for making them watch it. Once, after a screening I hosted, an audience member thanked me for giving them explicit permission, up front, to not like everything. But there’s an important distinction between not liking or not agreeing with something, on one hand, and rejecting it outright on the other.

Whether we realize it or not, we’re conditioned, with all of the media we consume, to expect certain elements to be standardized and familiar, so that we can immediately figure out where we stand and apply simple criteria to evaluate our experience – whether it was funny or entertaining, whether it was worth $12 and two hours of our life. When a product of mainstream media subverts or tweaks those expectations, even slightly, it causes an uproar. The final episode of The Sopranos is a brilliant example of this. “How could they!?” And I think, on some level, that that has led us directly into the deeply dysfunctional world we inhabit today – to the widespread and striking inability to imagine someone seeing differently than we do without being wrong.

The “credulous” person really suffers from a difficulty in believing, not an ease in believing: give him an array of assertions and he will always believe the one that requires the least expenditure of believing energy. He has a weak believing muscle and can only believe what is easy to believe. He can only digest what has been prechewed. The fact that we call this disease credulity when it is really incredulity reflects vividly our culture’s fear of belief.

Peter Elbow, ibid.

We believe that, if we try believing in something, even for a moment, we might become infected by that idea, trapped within it, stuck believing it forever. I think the “subject”-oriented university encourages this, exhorting students to identify and clarify their deepest held beliefs and convictions, and to use those as a basis for their very selfhood and sense of direction in the world.

Whereas, in my opinion, partly informed by Peter Elbow and my own teaching experience, the opposite is true: the more we can practice believing disparate things, especially in a low-stakes environment, the healthier our relationship can be with our beliefs themselves, with people whose beliefs differ from ours, and ultimately, with the elusive abstraction of Truth itself. To me, the scariest thing about the fake news controversy is the idea, on either side, that truths should be simply obtained, verified, and agreed upon. Facts can be objective chunks of information, but beware anyone who lays exclusive claim to the Truth – whatever their ideological orientation.

If we can use our believing muscle to vividly imagine what the world must look like through very different eyes, we actually gain perspective and wisdom, as well as empathy and agency in our relationships to the people and events around us. It doesn’t mean we agree; it doesn’t mean we believe what they believe. It’s just a brief experiment, an excursion into a different world. But, culturally, we treat this as a gateway drug, like it’s Reefer Madness all over again.

What we practice in experimental media class, in a very contained and careful way, is believing. I think art has this power, power to give us opportunities to get better at believing things, at practicing the skill of projection, and letting go of our subjecthood in a way that isn’t, in fact, hazardous, but actually extremely healthy. If we encounter a way of seeing that makes us angry or anxious or scared or disgusted, if we practice believing, we get to be curious about it, wonder why, what’s behind that, and what we can potentially learn from the distance between this particular artist’s way of seeing and our own. Again, that doesn’t mean that we have to agree with that perspective, or, God forbid, to like everything that we watch, see, or hear. I have no desire to see Vito Acconci with a raw cow tongue in his mouth ever again. But do I regret seeing it, having had that experience? Ultimately, no.

A willingness to experiment with believing in order to understand, a willingness to be curious, at least initially, rather than dismissive and pissed off – this effort towards empathy is the furthest thing from dangerous. It’s actually crucial, at this point, to our resilience and sanity, as individuals and as a species. Given that, I’d think such a believing game – via the Art department – would be a meaningful investment for a public university, worth funding whether or not the outcomes are easily quantifiable.

The only risk in so doing, for the university, is perhaps that when the student loan payments come due and the collection calls are made, that the voice on the other end of the line will reply, simply, “ça ne m’interesse pas.”