What Constitutes “American” Art?

Minnesota Museum of American Art invites five curators, from a diverse range of cultural backgrounds, to select work that might complicate and crack open the notion of American-ness.

The Minnesota Museum of American Art (MMAA) set about the task of creating a show asking, “What is American art?,” and emerged with an exhibition as messy as the question itself. With five different curators selecting work, the response couldn’t help but be chaotic, but perhaps the frenzied, loose structure of the exhibition is a fitting tribute to a country that’s composite and contradictory by nature, with a history stained with genocide and slavery, but also a national character that’s inextricably linked to the generations of newcomers who’ve arrived here in waves of immigration from all corners of the globe.

At a panel discussion for the show, MMAA Executive Director Kristin Makholm explained that the idea for the exhibition came after Theresa Sweetland, the museum’s new Director of Development and External Relations, mentioned that, ever since she’d started in her position last summer, people had been asking her to define what a museum of American art is, exactly — what it does and who it’s for. “I fumbled around,” Makholm recalled. “I’m the director and I’m supposed to know the answer to that…. It’s squishy, and it’s messy: there are artists from Canada and artists from South America. And what about people who live here but were born elsewhere? There’s just a lot of flux in that concept.”

Later in the summer, Makholm and Christopher Atkins, who recently joined the museum as Curator of Exhibitions and Public Programs, went to visit the Whitney Museum, which had just opened their new building with an exhibition called America is Hard to See. “It was meant to talk about why that [notion of ‘America’] is so hard; the aim was to throw that concept open,” Makholm said. “And yet [the Whitney’s exhibition] still pretty much boiled down to showing the canonical works in a big museum in New York City… I didn’t really get a sense of the squishiness or the messiness inherent in the central concept. I thought, in this day and age, we have got to be able to come up with a more nuanced idea of what constitutes American art.”

And so, for their exhibition, American Art: It’s Complicated, MMAA brought in four outside curators (the fifth being Makholm herself) to open up the question anew. Each of the guest curators — Seitu Jones, Oskar Ly, Maria Cristina Tavera, and Dyani White Hawk Polk — are artists in their own right and come from different cultural backgrounds. The show doesn’t seek to define American art as much as it aims to offer threads of understanding about the complex weave of culture and conflict that makes America what it is. The curators chose to feature a mix of established and emerging artists, from our current moment and also from the past, born in the United States and elsewhere, who together voice a cacophony of human experiences.

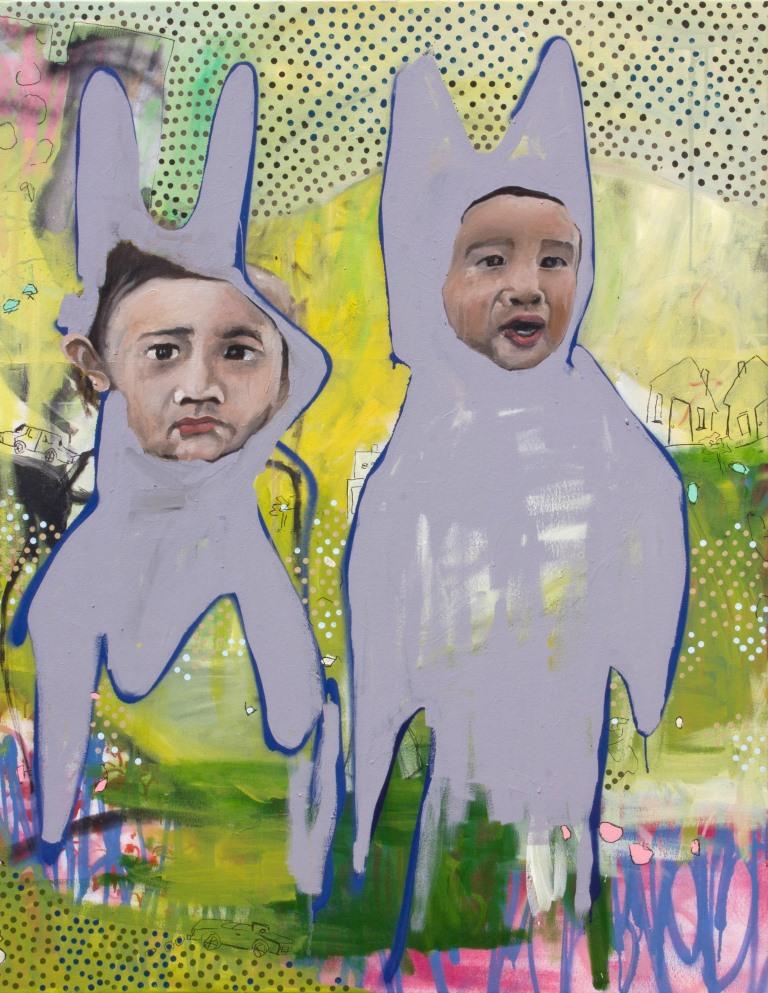

There’s a strong presence of immigrant artists in the show, many of whom are emerging voices. For example, Chantala Kommanivanh (chosen for inclusion by Ly), uses found images from Laos with an abstract, graffiti style in Cousins in Rabbit Suits. The work depicts two children in rabbit suits in an almost storybook landscape, harmonizing a sense of the homeland with a contemporary hip hop aesthetic. Makholm selected a photograph by Wing Young Huie, one of Minnesota’s most celebrated artists and a Duluth-born Chinese-American, for the exhibition. In President and Founder of the Asian Worldwide Elvis Fan Club, Houston Texas Huie captures a Vietnamese couple posing stoically amidst their Elvis paraphernalia. The work speaks to the tenacity and dedication of the couple, who, Huie notes, were inspired by “the story of how a poor, backwoods outsider could overcome his circumstances and become a global icon.”

There are voices conspicuously missing from the exhibition, however. Most glaring is the lack of African immigrant artists — a particularly noteworthy omission given Minnesota’s sizable African population and when you consider that Somali immigrants are the fourth largest immigrant group in the country (behind Mexico, India and Laos).

That said, the show makes no claims to being encyclopedic in its scope. And there are a number of pieces by African-American artist Maurice Carlton, whose work curator Seitu Jones chose to feature exclusively for his selections. “I decided to make it about me, to tell my own story,” Jones says, noting that he chose Carlton because of the artist’s influence on his own life and work. An African-American who worked for the railroad as a sleeping car porter for 20 years, Carlton became an artist after retirement and was based in the Rondo neighborhood of St. Paul. Growing up, “I saw Maurice’s work out of the corner of my eye,” Jones says. “I saw it on the street as part of the streetscape. It became something that was omnipresent.” On sign posts, at the inner city youth league, and in other community spaces, Carlton’s transformed broken dolls, weathervanes and globes into artwork, though he called himself a toy maker rather than an artist. Carlton “wanted to visually render many of the issues that faced the African American community,” Jones explains. His curatorial decision to present work exclusively from Carlton is, itself, a way to further open the canon of American art to those issues and experiences. (Many visitors to the MMAA have likely never before heard of the St. Paul artist, and if they walk away with one artist’s name to remember, it’s probably going to be Carlton’s, given the sheer number his pieces featured in the exhibition.)

In addition to the diverse cultural spread of American experience, the curators also took pains to pay tribute to the country’s landscapes. In the curators’ talk, White Hawk Polk spoke of her deliberate attention to the land as a particular focus in her curatorial choices. That interest is evident in a number of pieces, from Brian Frink’s gorgeous abstract landscape, Memory of Water, to Catherine Meier’s vivid charcoal drawing, Sage Creek Rim Road, which descends into the gallery from a huge roller.

White Hawk Polk’s selection of Will Wilson’s Air #2, a photograph of young Native Americans overlooking the Grand Canyon, is displayed next to one of Ly’s selections, Gabriel Z. Traveller’s Hunter. In Air #2, a young man wears a handkerchief over his mouth and holds his fist out over the vista beyond; in Hunter, we see a man in military garb holding a gun, with the angle of the camera held in such a way that the figure is overpowered by the sky above him. Both pieces capture the vastness of an American sky, and both comment on masculinity. But Wilson seems to celebrate a defiant spirit, while Traveller is more interested in his subject’s overbearing power.

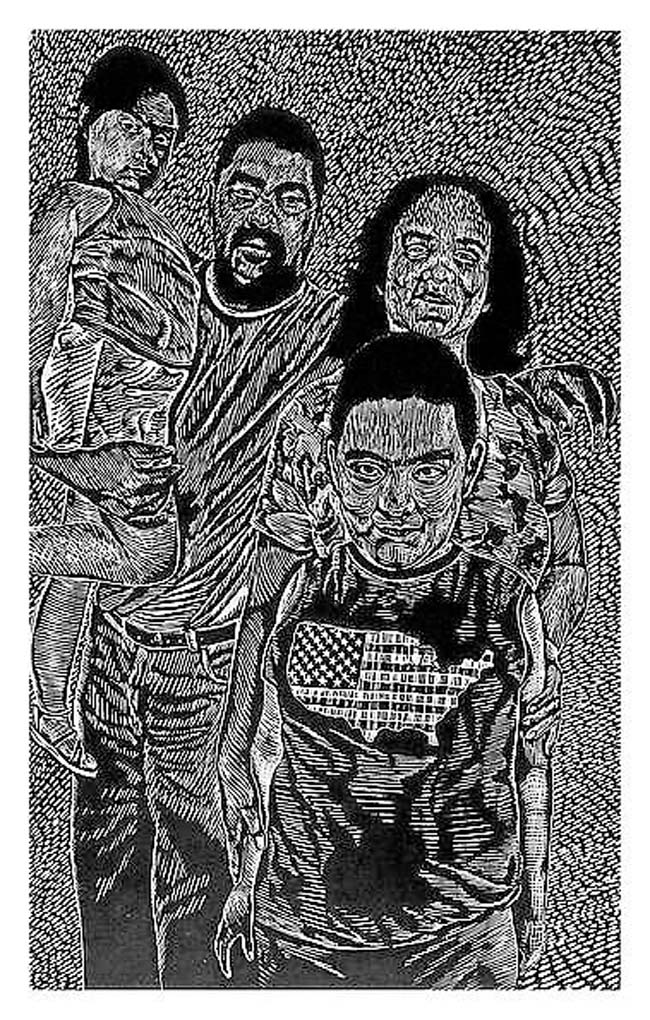

Tavera’s selections investigate issues of land and the vagaries of ownership by questioning how we define the contours of America. “A third of Mexico was taken during the Mexican American war,” she says. “What represents someone who considers themselves American?” Raoul Deal’s Immigration Series #9 (chosen by Tavera) takes on issues of identity for immigrant Americans head-on. In the wood-block print of a presumably Mexican American family, the oldest son stares out at the viewer with an American flag t-shirt. The photo captures something of the experience of having a Mexican-American identity, with a nod to the complicated layers of American-ness.

The exhibition is strongest in its re-examination of history, with an impressive showing of Native artists, in particular, that challenge mainstream narratives of American history in sometimes heartstopping ways. Jim Denomie’s Off the Reservation, or Minnesota Nice (chosen by White Hawk Polk) and Francis J. Yellow’s They Said Treaties Shall be the Law of the Land (chosen by Makholm) both deconstruct white supremacist narratives of U.S. history with brutally effective truth-telling.

For her part, Makholm’s curatorial approach is a responsive one, bringing out an assortment of works from the 4,000-some pieces in the museum’s collection she thought might resonate with pieces the other curators had selected. For example, Weasel Trail— Piegan, 1900, a photograph by Edward Curtis drawn from the artist’s controversial collection of (posed and elaborately orchestrated) images portraying Native Americans. Not only did Curtis frequently provide costumes for his subjects but, as was common among white European artists of the time, he portrayed his subjects as part of a “vanishing” race, objectifying his sitters in poses and configurations more akin to idealized natural history dioramas than documentary.

In the exhibition, Curtis’s work is presented next to Pao Houa Her’s photograph of a Hmong veteran, one of a series of photos in which Houa Her brings to light the many Hmong veterans whose contributions to the Vietnam war have since been erased as part of the U.S.’s covert operations in the Southeast Asian conflict. Both photographs hold with them untold stories, but they offer two very different methods of revealing those stories. Where Curtis projects European notions of what “Native” looks like onto his images, Houa Her actually comes from the community she is photographing (though from a different generation, and of a different gender than her subjects in the series). The juxtaposition of works communicates how important the relationship is between artist and subject, and how that relationship informs the work’s message.

The pairing also speaks eloquently to the “squishiness” of American art, not only with regard to which artists we include in that cultural conversation, but also how we evaluate and critique artists who have traditionally been considered part of the “canon.” As Makholm commented, “There will be things in a collection of American art that you need to open up and unpack in order to see the cracks that exist.”

Related exhibition information: American Art: It’s Complicated is on view from November 5, 2015 to January 3, 2016 at the Minnesota Museum of American Art in St. Paul.