Dan Graham’s Postmodern Dreams, Come to Life

Camille LeFevre ruminates on Dan Graham's retrospective at the Walker, and on the "peripatetic, insouciant, and incisive" ways in which his work has foreseen the highly mediated world we now live in

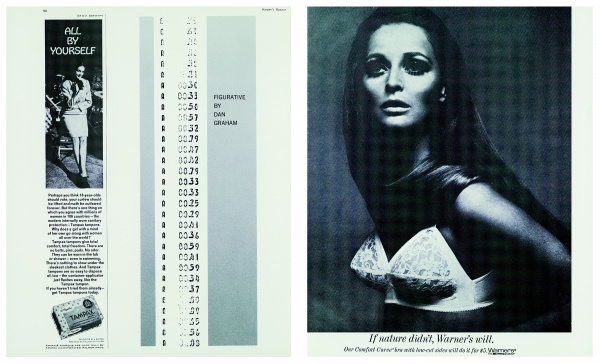

The work of American artist Dan Graham is so intellectually peripatetic and playful, so insouciant and incisive, diverse in media and in execution, one hardly knows where to begin in writing about the retrospective, Dan Graham: Beyond, currently at the Walker Art Center. So, how about taking a cue from the work itself? In particular, let’s start with the pavilions and structures one is invited to walk by, look at and look within, enter and inhabit.

These structures are an integral part of the traveling exhibition, organized by two coastal art institutions: The Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. Two of these installations are familiar to the Midwestern art aficionados who frequent the Walker — Two-way Mirror Punched Steel Hedge Labyrinth (1994) is part of the Minneapolis Sculpture Garden collection, and New Space for Showing Videos (1996) has occupied the Walker lobby.

Enclosed within the confining walls of a museum gallery, however, Graham’s structures and their effects acquire a new intensity. They’re designed to incite and evoke a relationship between the viewer and object that challenges us — in a thoughtful yet fun way — to re-consider time, space, and surfaces. There aren’t any passing clouds, waving tree branches, traffic noises, soft grass patches, birds or squirrels to distract us, as they might when these pavilions are placed outdoors.

Instead, it’s just us-and whoever else is passing by-and how we see ourselves, or don’t, in glass walls that may be reflective or transparent, sometimes mounted with one-way or two-way mirrors. In other words, simply by entering the gallery, we activate the art and the space it inhabits and contains. We, the viewers, are not just spectators, but participants — performers in our own, singular iteration of Graham’s art. And it’s this performativity, inherent to so many of Graham’s structures, that makes them intriguing. Or rather, as Graham said during a recent tour of the exhibition, ” [they are] funhouses for children and photo ops for parents.”

Of course there’s something very meta, very reflexive, even narcissistic about the way we’re prompted to engage with Graham’s structures. The walls’ shifting transparency, opacity, and reflectivity continually places and re-places us inside or outside, as we move about the piece. Where, exactly, we are in time and space continually changes; our sense of public and private spaces, of whether we’re the subject or object of viewing, even our awareness of time, present or past, is in continual flux.

Graham’s work is about “the way one experiences the space of the self,” a precursor to our 21st-century culture of mediated identity, of seeing ourselves as reflections on various screens (computer, phone, television).

In Opposing Mirrors and Video Monitors on Time Delay (1974), a room in which there are two cameras/video monitors that shoot and mesh the viewer’s movements with a slight delay, you can clone yourself to infinity and then observe the results. For example, I figure-eighted around the monitors in an invisible infinity symbol, stuck out my tongue, and laughed — just to see the effect. Sure enough, moments later, there I was, my past and present bodies conjoined in a moment of screen-time all my own. And that was enough of that.

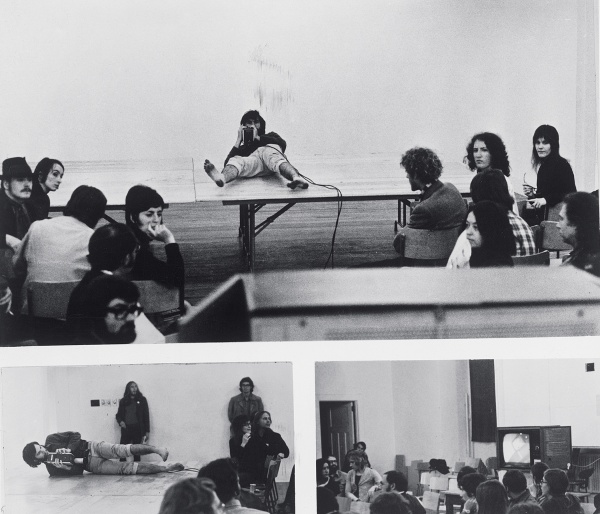

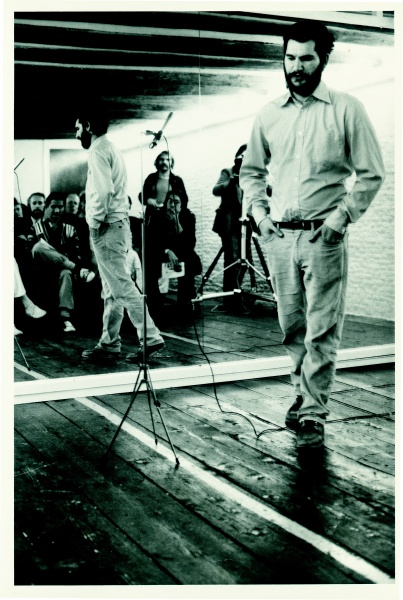

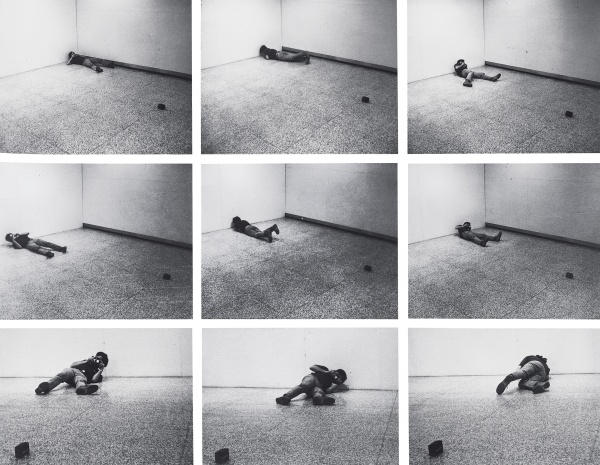

Graham has been, himself, the subject of many of his video works. He filmed himself rolling down a hill (Roll, 1970) and rotating in a room (Two Correlated Rotations, 1969). In another, Graham is standing in front of a mirror, first facing a group of viewers, describing both his own movements and the audiences’ behavior, then facing the mirror to describe his own and the audience’s reactions (Performer/Audience/Mirror, 1977). In Body Press (1970-72), he and Susan Ensley alternated filming each other as each walked, naked, through a room filled with cameras.

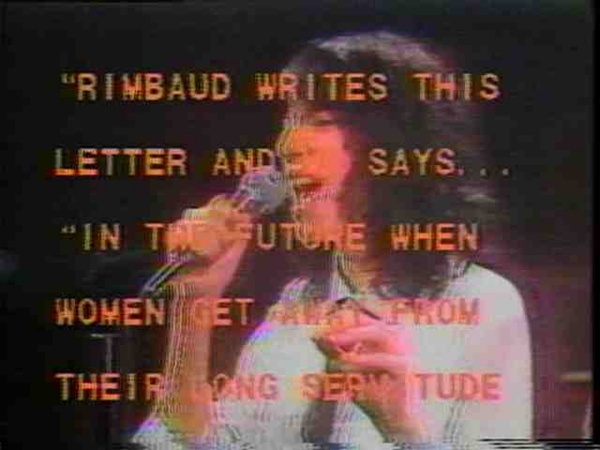

In his article for the New York Times, Randy Kennedy quotes the MOCA-LA curator, Bennett Simpson, as saying Graham’s work is about “the way one experiences the space of the self,” a precursor to our 21st-century culture of mediated identity, of seeing ourselves as reflections on various screens (computer, phone, television). Chrissie Iles, the Whitney curator, adds, “The pieces make sense, in a way, even more than they did ten years ago, when they had a completely different kind of reading, because we hadn’t gotten to this stage yet, the stage of Twitter and Facebook and Flickr.”

And this is why, ultimately, I find Graham’s structures rather cold. Sure, his magazine pieces are a hoot: the artist’s Homes for America snapshots (1960s) and Corporate Atrium Garden (1987) studies of corporate glass skyscrapers provide trenchant commentary on communities and buildings. And his Swimming Pool/Fish Pond (1997) offers a sensory illusion that’s nostalgically delightful. But watching video of adults standing around, as kids play in the pavilions outdoors and on location, while sitting in those pavilions in the gallery — it just seems tired.

Perhaps it is the performative redundancy of such an experience — the meta-commentary on top of commentary — that feels worn out to me. Or, perhaps my capacity for such “performance” is simply exhausted; maybe Graham’s indefatigable propensity for rumination and intellectual investigation as play just played me out. Musing on Iles’ assertion, during the Walker’s exhibition tour, that Graham’s work is “consistently relevant and new in every decade,” I couldn’t agree more.

I just sometimes wish that all those Postmodern aspects of American life that Graham has explored, aspects which are now a fact of everyday existence — fractured narratives, the contrivances of reflexivity, instant intimacy, compressed and conflated notions of time and space — weren’t so obviously true. Graham’s multiverse is no longer a hypothetical cosmos that may contain our universe as well as others. Instead, it is our one and only. It is us.

Noted exhibition details: Dan Graham: Beyond will be on view at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis through January 24, 2010. On December 3, BodyCartography Project will offer a movement-based tour through the exhibit as part of the Walker’s Free Thursday Nights programming.