Wild Rice, Frybread and the Winding Road Home

Connie Wanek reviews Linda LaGarde Grover's evocative new novel, "The Road Back to Sweetgrass," which centers on the young men and women who are drawn from the Northland's reservations and into the larger world.

‘Home is the place where, when you have to go there

They have to take you in.’

‘I should have called it

Something you somehow haven’t to deserve.’

–Robert Frost

The annual wild rice harvest is underway in northern Minnesota, just as Linda LeGarde Grover’s new novel, The Road Back to Sweetgrass, has appeared. This is perfect timing, for on Grover’s fictional Mohzay Point Reservation, ricing is one of the most important rituals that bind the people together and help the Ojibwe culture endure. Ricing brings people home.

Among the most beautifully evoked scenes in the book are those early autumn days spent on Lost Lake. The rhythmic labor of knocking ripe rice into the boat, “the softness of the sunlight, and the breeze, light as sheer curtains blowing in an open window,” create the ideal time for reverie. In the privacy of the ricing boat, surrounded by rustling, life-sustaining grain, the heart opens to its own truth, and admissions and revelations occur that set the book’s major events in motion.

The novel follows a small group of American Indians as they venture into the larger world and then return to their reservation, their nation within a nation. As the book opens, it is 2014, and Margie Robineau, the book’s central character, is “approaching elderhood.” She is considered the reservation’s finest maker of frybread. Grover says Margie’s creation as “was so light it all but rose from the plate, so tender as to be all but unfelt in the mouth, so tasty that the very thought that the moment couldn’t last forever brought to the eater an undertone of sorrow that added an intangible brine, like a grain of salt from dried tears yet to be wept.”

It’s interesting (and significant) that frybread, which did not begin as a traditional native food, has become one over the decades. What is it exactly? Here, straight from the book, is Margie’s recipe — you may wish to try your hand at it:

FRYBREAD

Almost two cups of flour

Almost a tablespoon of b.p.

Pretty small-size pinch of salt

A little sugar, maybe a teaspoon (this is up to you if you want it)

Mix this in a good-size bowl, and then make a little river, in a circle. Add warm water to make the dough nice and soft. Cover and give it a little rest after you mix. Fry it like doughnuts. Good with butter, or honey, or jelly, or syrup. Or plain. This makes a good lugallette, too. For lug, bake it in a pan. Cut it up. But grease the pan first.

Margie’s recipe, itself, makes a little river, in a circle; her instruction ends at the beginning, by reminding you to grease the pan first. Throughout Grover’s novel, time is not linear, but circular. Readers are gradually taken back to 1970, at which point we reverse course and hopscotch forward to 2008. As the book ends, we are back to the present, listening to a story from almost a century ago. This might sound confusing, but it isn’t, thanks to Grover’s skilled prose. As Faulkner said, “The past isn’t dead. It isn’t even past.” Events, even from long ago, are very much alive in the people they haunt, or bless, in this novel.

Narration shifts, too, between third and first person, as various characters are allowed to tell their own tales. In this respect, one is reminded of the linked short stories that comprise Grover’s first book of prose, the prize-winning Dance Boots. What is the difference here? How is this latest a novel instead?

In The Road Back to Sweetgrass, readers follow the same characters throughout, and their tales are much more closely interconnected. The chapters do not stand independently as individual stories. The web of narration is tighter.

______________________________________________________

Here is part of Margie’s secret: unrequited love; the LaForce family land allotment in Sweetgrass; and not too much sugar in the frybread when you add that little bit.

______________________________________________________

Also, the two books’ concerns are quite different. Dance Boots is tied thematically to the disastrous Ojibwe experiences surrounding Indian Schools, while here Grover focuses on the young men and women who are drawn away from the reservation into the larger world — for school, for jobs, for adventure. They join the military and fight in Vietnam. The borders of the reservation are porous, and yet part of the strong appeal of the book is that home calls them back, sometimes with the faint scent of sweetgrass, deeper than memory. For example, one of Grover’s characters, Michael,

“…fled down I-35 right in the middle of ricing, gone overnight it seemed, like the Lost Lake geese who flew south in autumn. He flew only as far south as Minneapolis, like a lot of people did from reservations up north, Indians on the road with a destination in mind, looking for work, for opportunity, for relatives who were homesick. To escape for a while. When their hearts’ seasons changed, they flew back home, in a migratory pattern that had come to seem as natural and inevitable as the patterns of birds.”

Another important character in the novel, Dag Bjornborg, is a “mixed-blood,” Ojibwe and Norwegian, who comes to Mozhay Point during ricing to find out who he really is. He was conceived as a result of rape, and his Ojibwe mother was coerced into giving him up for adoption. Yet his arrival marks the beginning of one of the most heartwarming and affecting episodes in the novel. He finds his home, his mate, his future among the teasing, generous souls gathered at Lost Lake to gather the wild rice, the manoomin. He is “Dag,” he is “dog,” he is “Animoosh.” A story seems to resolve in this homecoming, but it doesn’t really — it merges into a new narrative, which itself doesn’t end. Rivers in circles. And real life is complicated, even in fiction! In the fullness of time, good can emerge out of wickedness.

The best books do not simplify or preach. They lay before the reader the mysteries and contradictions that define our lives. Frybread: while it is many generations old as a staple in many Native American tribes, it was first made with the flour, sugar, salt and lard given to displaced Native people who faced starvation unless they made use of these government commodities. Another blessing out of tragedy. Some Ojibwe have French last names, and in the novel, the boy Wazhushk was also called Washington, for a white man’s ease. Children born of two races can belong in both, rather than neither. Ojibwe who spend years away from the reservation still have a spiritual and physical home there, and find welcome. And out of the most basic ingredients, Margie Robineau creates magic. What, jealous cooks want to know, is her trick?

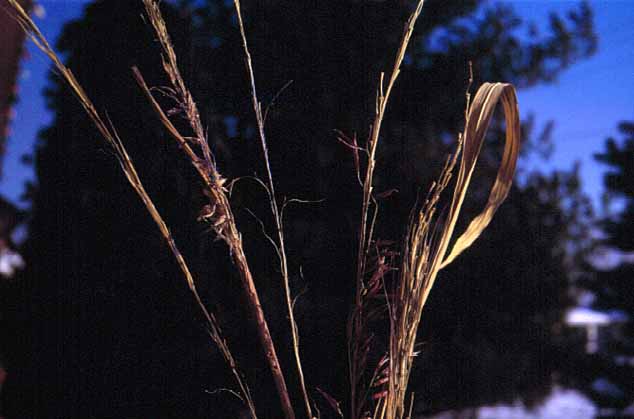

Wild Rice, 1946. Photo by Monroe P. Killy, courtesy of the MN Historical Society.

“Here is part of Margie’s secret: unrequited love; the LaForce family land allotment in Sweetgrass; and not too much sugar when you add that little bit. But without Zho Washington’s grandmother, those three would have remained unconnected — as would have the ingredients that went into her mixing bowl and came out frybread, so would have the ingredients that went into her existence and came out Margie’s life.”

Grover introduces the book with a preface of sorts, a prose poem really, called “The Odissimaa Bag.” It’s a lyrical, mythic passage in which we learn about the Ojibwe custom of wrapping a baby’s umbilical cord, when it has detached, in dried sweetgrass and placing it in a “small deerskin bag sewn with red thread and blue beads…an odissimaa.” In the novel this pouch is buried, but ever after it is the baby’s spiritual link to a particular place, to ancestral land. It is a powerful symbol of the longing for home, of spiritual belonging. I love Grover’s frequent use of Ojibwe words, sometimes explained in part, sometimes in full, sometimes not at all. I found myself sounding out these words slowly in a whisper, like someone learning to read.

This may be the most profound of all the ways that tell people they are home, a particular language, phrases given to a child so early that the words seem ever after to come from the unconscious, or maybe the pre-conscious. After I finished this marvelous book, I turned back to “The Odissimaa Bag” and to the first chapter, rereading with a deeper understanding and the joy of recognition, having come to know the good people of Mohzay Point. In doing so, I followed the path of a little river, in a circle.

Related information and events:

Linda LeGarde Grover will be at the Barnes & Noble Booksellers in Duluth, Minn. for a book-signing for The Road Back to Sweegrass on November 15 at 1 p.m. Her earlier book of short stories, Dance Boots, was recently selected by Northland readers as Duluth’s One Book, One Community selection for 2015; related events will be announced by Duluth Public Library early in 2015. Find more information about the new novel on the University of Minnesota Press website.

Connie Wanek is the author, most recently, of On Speaking Terms (Copper Canyon Press, 2010). Her work has appeared in Poetry, Atlantic Monthly, Virginia Quarterly Review, Narrative, Poetry East, and many other publications and anthologies. She has been awarded several prizes, including the Jane Kenyon Poetry Prize and the Willow Poetry Prize, and she was named the 2009 George Morrison Artist of the Year. Poet Laureate Ted Kooser named her a 2006 Witter Bynner Fellow of the Library of Congress. She has a new book of prose, Summer Cars, from Will o’ the Wisp Books, and her next volume of poems, Rival Gardens: New and Selected Poems, will be released in 2015 from the University of Nebraska Press. Find more at www.conniewanek.com.