Joie Musicale

Our music columnist, pianist and composer Jeremy Walker, ponders his teenaged son's deceptively simple question about making a career in the music industry -- not about the money or other practical concerns, but this: "Is being a musician a good life?"

A few weeks ago my son, Sam, asked me if being a musician is a good life. He is reaching that age when you start to think about your future, and his various interests and all the possible paths they could take him, are on his mind — music being one of them. And his question’s a great one, and one that deserves a careful answer.

I have always taught my son to follow his own calling, whatever that might be. I don’t want him to choose his life’s path based on economic security, convention or the pressure to conform to “practical” expectations. So, I would never discourage him from a life in music for those reasons. Besides, he has been around people working in the music industry his entire life, so he is well acquainted with its day-to-day struggles: every working artist is all too familiar with blank stares and empty chairs. And my son has witnessed all of that, since almost before he could walk.

And still, he tells me he might want to be a musician — I mean for a living, for life. Not as a hobby, or a serious avocation (though they’re wonderful things — of course, playing music is always a wonderful thing).

The economic news has never been good for musicians, and maybe it is even worse now. But he’s not asking about money. His question is this: Knowing what I know, could I tell my son that being a professional musician is a good — no, great life? When I really know something, it feels like a long ball. I mean, the answer or feeling or sound comes arcing from the back of my brain to the front, in a way that’s clear and thrilling. My answer for Sam felt like that. And when he asked I told him, unequivocally, yes — yes, music is a wonderful way to spend your life.

And I think that needs to be said. It is so easy to complain all the time. I am no Pollyanna: there is a lot of struggle involved with taking this path. But if I am fully honest, my life in music, taken on the whole, has been almost pure joy. It feels self-serving to list all the transcendent moments music has given me, moments I would not have had in any other life — there are too many to list anyway. But I can say that a life in music is a life rich in discovery, challenge, expression and community. So, I could tell my son, without reservation, that if music beckons him, he should listen to that call without hesitation. And in telling him that, maybe for the first time, I felt that way, too. Somehow, by looking for a truthful answer to his question, I could finally allow myself to be fully grateful for everything I have experienced, and will experience, in this life in music that I’ve chosen.

This question of joy, specifically, in the life of a working musician: Others have answered it too, better than me, and they have been living and playing by the truth of it for a long time. I think about the whole Bates family, regulars here in town; the family patriarch, Don Bates, has been making and teaching music for decades. His commitment to sounding great and having a good time is something to which all of us owe a debt of gratitude. I have played with Chris and JT Bates many time, and I’ve written about their continuing contribution to our musical life in this column. And Chris Bates, in particular, exemplifies the kind of joy I am talking about here. There is so much sheer happiness in his sound and his musical presence. We have played together many times over the years (although not nearly enough as far as I am concerned), and being on stage with him is always an education in the feeling of music: you can hear it in his beat, in the bounce that runs through his playing. I always get the sense from Chris that, as long as we keep playing, everything will be cool. Obviously, the polish and technique in his performance show all the long hours in practice rooms with exercise books and a metronome — musical joy comes with calluses. But that is the bargain that music strikes: the harder you work, the freer you are in the music, and the more fun you’ll have when you play.

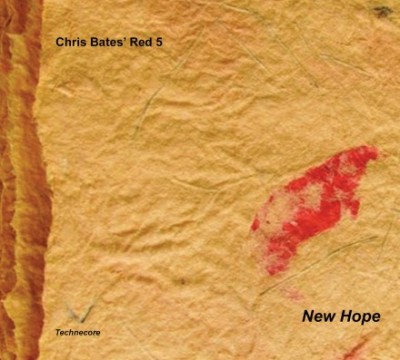

Chris Bates is in a lot of bands. Some months, it seems he takes up residence at the Artists’ Quarter. I always enjoy hearing him with other praticiens de joie, Dean Magraw and Jay Epstein, in their band Red Planet. Last month, Chris released his first record as a band leader under the name Chris Bates’s Red 5 (red seems to be a thing for him). The album is called New Hope and is available on iTunes; I just downloaded it, and all of you should pick it up, too. Better yet, go to a live show and buying an actual CD. Regardless of how you hear it, though, New Hope is a great record. The compositions are strong and all the players are terrific improvisers. Chris showed real musical wisdom in putting this band together. First, his brother, JT Bates, is on drums. JT’s always a good choice, but particularly apt here; the brothers have a special rapport. Then, on saxophones, Chris chose Brandon Wozniak and Chris Thomson; both are creative improvisers with contrasting but complementary tones and personalities. Brandon plays with a restless intellect and a warm, dry tone. His solos sound like rhetoric, reasoned and impassioned. Chris Thomson plays with a fuller, juicier sound. His playing is deeply melodic, with a bouncing sense of swing and groove. Zack Lozier plays trumpet with the band, with just the right combination of bravado and warmth; on an instrument given to histrionics (louder, faster, higher), he develops his ideas with a strong grounding in harmony and communal groove.

New Hope sounds to my ear like a statement of confidence, that despite all the bad news these days, there is still a reason to make music with joy and conviction. The ultimate outcome will likely have nothing to do with career advancement or mortgage payments, but everything to do with quality of life. (Read more about Chris Bates’ music here.)

Another such example, solidly in the joyful noise camp, is Brandford Marsalis’s latest, Four MFs Playing Tunes. I won’t say much about it here, but check it out. Also worth a listen is Marcus Roberts with Bela Fleck — Across the Imaginary Divide. These two musicians coming together represents an important, well, coming together to tap the main vein of American folk and blues music: it’s banjo and jazz piano trio, and they work well together. (Also, if you haven’t already, watch Bela Fleck’s documentary Throw Down Your Heart, where he traces the African origins of the banjo. It is deeply moving and beautiful.)

In keeping with this theme of joy and gratitude, I urge you to continue to check out musicians playing in person. The Icehouse is doing a lot of great things, with food and cocktails, as well as music. Also, the venerable and always important Artists’ Quarter continues its commitment to live jazz; Davis, at the door, will make sure you feel welcome and loved. To paraphrase an old outlook: Given how bad the world is sometimes, the surprise isn’t the difficulty of a life in music, but how wonderful it can be. That’s the line I want to be on.

______________________________________________________

Related events:

Chris Bates and Red 5 are playing Monday, October 29 at Icehouse in Minneapolis, and Jeremy says he plans to be there, because “as good as New Hope is as record, jazz is best experienced live.”

Listen to some rehearsal samples of tracks from the new record below:

______________________________________________________

About the author: Jeremy Walker is a composer/pianist based in Minneapolis. He has performed with Matt Wilson, Vincent Gardner, Wessell Anderson, Marcus Printup, Ted Nash, Anthony Cox, and other notable musicians. Jeremy was the owner of the now defunct club, Brilliant Corners and co-founder of Jazz is NOW!. Walker teaches piano at K and S Concervatory in Woodbury, MN. He is composing the score for the upcoming documentary Photographic Justice: The Corky Lee Story.