All in the Family

Ann Klefstad ruminates on an intriguing new family-themed exhibition at the Tweed Museum in Duluth: "You and Yours," a curatorial project by Patricia Briggs, with work drawn from contemporary art in the Tweed's permanent collection.

It has been difficult for me to think about You and Yours, independent curator Patricia Briggs’ interesting family-themed show for the Tweed Museum of Art in Duluth. I suspect this has something to do with how hard it is to confront the issues that the exhibition raises. I finally called the curator on the phone — a conversation that had been often postponed because of crises, first in her family and then in mine. By happenstance, the period over which I struggled to process the ideas in the show was fraught with real-life reminders of how buffeted we are by our families, and how necessary they are to us as well.

Children as the makers of family

Even in families in which children are not present, childhood is defining: after all, we are all former children, and to tell the truth, our child selves are never entirely relegated to the past. The purpose of families has been, and remains, to be either nests for sheltering children (and former children) or bows that launch them like arrows into the world. So it is in families that the world of children is both known and disguised. It is there that our histories dwell, for good or ill.

The ways in which children constitute both their own lives and the lives of their parents are explored in several bodies of work in You and Yours: Katherine Yuksel‘s Two Boys Series, for instance, documents the interplay of the artist’s two much younger brothers. These photos, says Briggs “are beautiful, haunting, romanic — at once staged and not staged. They communicate the idea that children create and inhabit their own world when they play. The way the artist frames and sets up the shots suggests that they are staged scenes, yet Yuksel seems to tap into a world created by the boys themselves. The hints of darkness and trouble suggested in the work differs, I think, from the way children are so often portrayed historically in art — as all sweetness and innocence. “

Talking about the sculpture of Argentine-born Ana Lois-Borzi, who frequently uses stuffed animals or creates them in her work, Briggs writes:

Their bright colors, soft textures, and all-around cuteness make stuffed animals pleasing toys for both children and adults. One might argue, though, that stuffed animals are strange. They are highly abstracted hybrid characters designed to meld animal and human characteristics and they typically lack any real similarity to the animals they are meant to represent. With her oversized and playfully manipulated versions of these toys Ana Lois-Borzi reminds us that very strange characters populate a child’s most intimate world.

The Normative Family

Stuffed animals are not invented by children. In fact, adults often tell the stories of childhood, crafting them according to their own lights. Briggs noted in conversation that her history of teaching both gender classes and queer studies at MCAD has made her conscious of the artificiality — and sometimes the violence — of normative ideas of childhood, girlhood, boyhood.

These normative ideas are often translated into artworks. Briggs made her selections from the permanent collection of the Tweed in order to establish a kind of benchmark of normativity in the cultural history of family: idealized childhood as seen in David Erikson’s painting of his young blonde son in a rowboat; idealized motherhood as seen in a nineteenth-century Austrian Madonna; idealized family life depicted in a Flemish “flight into Egypt” image — the Holy Family, held together by love and divine mission, traveling a road into the unknown.

However, in these researches into the Tweed’s collection, she found surprises, too: Abraham’s sacrifice of Isaac is hardly idealized — but perhaps it can be seen as normative. Briggs remarked, “The sacrifice of Isaac: this is about the father or the state sacrificing the son. In my gender class, when you look at patriotism and sacrifice, you have to go back to Christianity. The father offering the son to die for a cause — religious or patriotic — is part of our construction of masculinity.”

Real and Ideal in Conflict

Ana Lois-Borzi‘s work brings up Briggs’ strongest feelings about the show, particularly with regard to the work that doesn’t even seem like an artwork: Register I: Jane Austen’s P&P Vol 1. On seeing the show today, this piece presents as a scatter of toys across the floor of two galleries. And this is what the artist intended. But it started life rather differently. Briggs writes this about it:

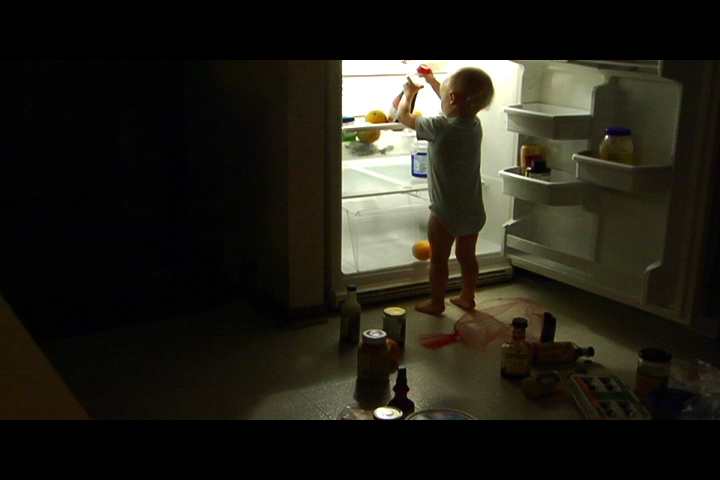

Ana Lois-Borzi is fascinated by romance novels, which typically present highly idealized representations of courtship and leave out the realities that come with raising children and keeping an orderly home….she represents each of Austen’s key characters via a category of objects gathered from her own home. For example, Austen’s heroine, Elizabeth Bennet, is represented by pieces of wooden track borrowed from the artist’s son’s toy train set. Miniature cars represent Darcy, the male love interest, and so on. When Lois-Borzi installed the piece, each line of the floor grid corresponded with a single character …. Having neatly set up the installation, the artist invites viewers — especially children — to handle and to move the objects that make it up. The order mothers seek to bring to homes is routinely it seems undone by those who live in it.

This function of art — to remind us of what we hide or forget or falsify — is the one that most interests Briggs in this show.

Work that reminds us of what we hide or forget or falsify — that is the function of art which most interests Briggs in this show.

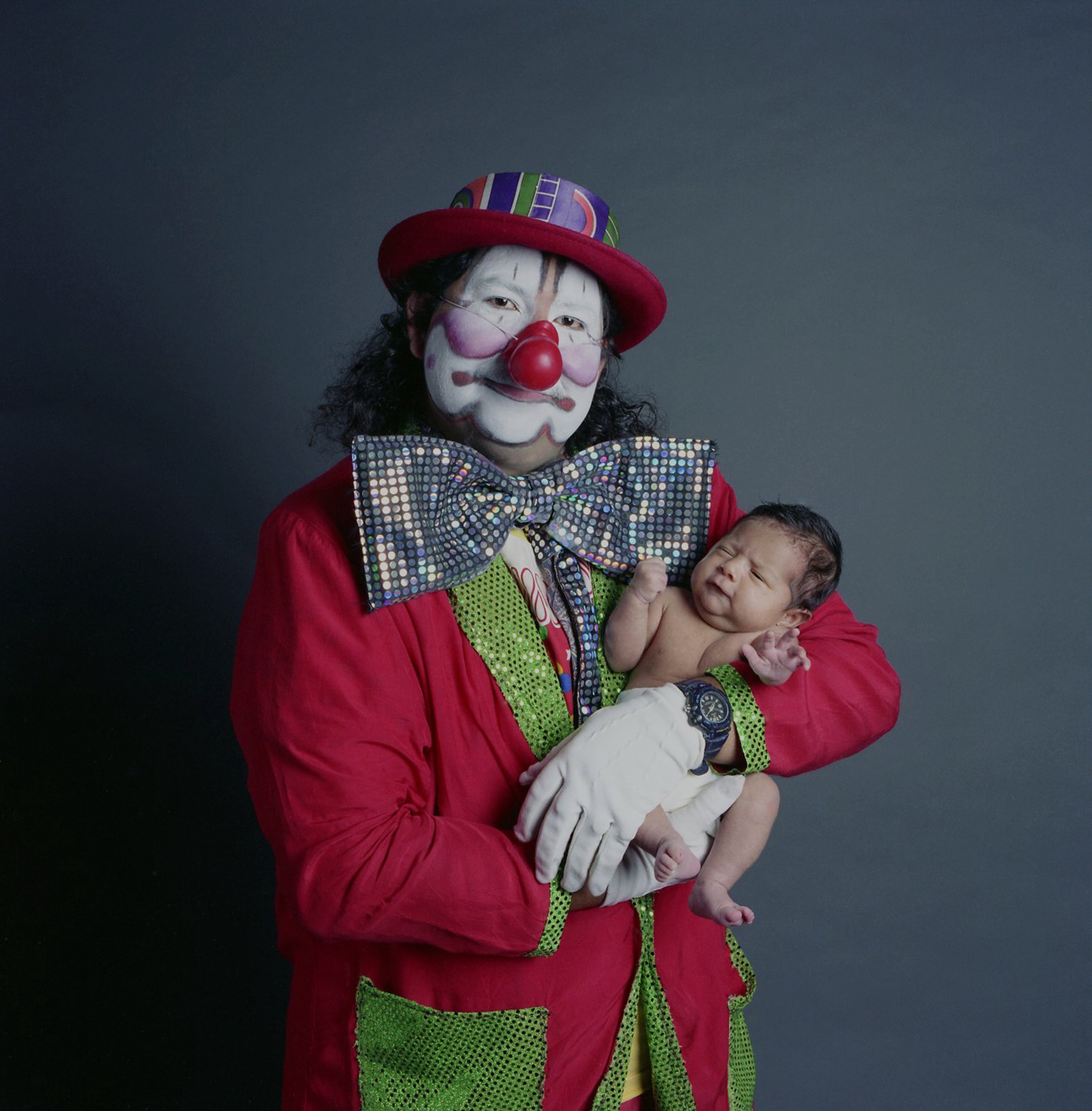

Xavier Tavera‘s strong photographs of fathers, dressed in their roles as workers and fighters in the world, cradling their infant children, reminds us both that fathers can be tender, and that often the world, and men’s own natures, do not make that easy.

Many of the videos in the show also address the tensions between what we as adults want childhood or family to be, and the reality of what often, helplessly, plays out in our lives.

Almost 5, a short video by Jennifer Steensma Hoag which Briggs says was the germ or genesis of the show, presents a young girl with eyes closed facing the camera. Her mother, behind the camera, is telling her, gently but firmly, to keep her eyes closed. As this becomes more and more difficult, the girl continues to ask her mother if she can open her eyes. The maternal voice, gentle but unyielding, continues to tell her to keep her eyes closed. This exchange becomes agonizing as it is drawn out and the girl’s distress increases.

Briggs notes, “For me, this piece represents the way a mother covers the eyes of her child, protecting the child from what she doesn’t want her to see. It is a loving thing but it is also oppressive and smothering. Mother and daughter are connected so purely, but this connection can result in a kind of painful, constant disciplining and smothering.”

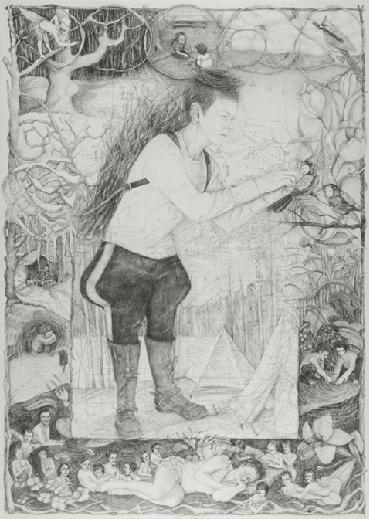

Amy DiGennaro‘s amazingly intricate drawings also address the ideal and the real of family life. She and her (former) partner, and the two children they had together, populate these lovely, loony accounts of family life imagined as a medieval manuscript; but her father (seen as a clown) and her mother (with gnarled roots for feet) seem to embody the traps and offenses that families can proffer in lieu of shelter or impetus.

How Artists Create “Family”

Originally, Briggs says, “I was interested in the way that motherhood and the idea of family were idealized historically in art, and how so many contemporary artists play with images that challenge them.”

But she found that artists also create, not just ideas of family, but new kinds of families as well. And those two kinds of creation can be liberating for all of us.

Briggs describes, for instance, Monica Haller‘s video of a girl plucking the artist’s eyebrows: “Haller worked for a few years in collaboration with Neva and Shantel, teens she met while doing a photography workshop. Haller, who is White, is interested in making real connections in her art and with her art, connections that bridge age, race, and class. Here, Shantel — who is African American — plucks the artist’s eyebrows. This is an intimate activity, the sort of thing girlfriends and sisters do together. Haller’s work is about real connections, and she uses her art to short-circuit barriers society often imposes between people.”

I ask about Briggs’ own relationship to family: How does being a “non-hetero-normative” individual form her ideas of family?

She responds, “I guess, as a lesbian in a long-standing relationship — we would be married if the law allowed — I can say that I live a relationship that does not conform to the stereotype of the ‘natural’ family. Yet, I could say the same for my four heterosexual siblings surely — or for most hetero families. In my siblings, for example, there are examples of foster care, single mothering, divorce, paternity ignored, split-up siblings, orphans, and so on. The ‘ideal’ family is unusual, it seems (or doesn’t exist), yet the idea of it still motors so much of what we think a family ‘should’ look like.”

Related exhibition details: You and Yours: Images of Family, a curatorial project by Patricia Briggs with work drawn from the Tweed Museum of Art’s permanent collection. The exhibition will be on view through October 17 at the Tweed Museum in Duluth.