Through the Eyes of a Muse

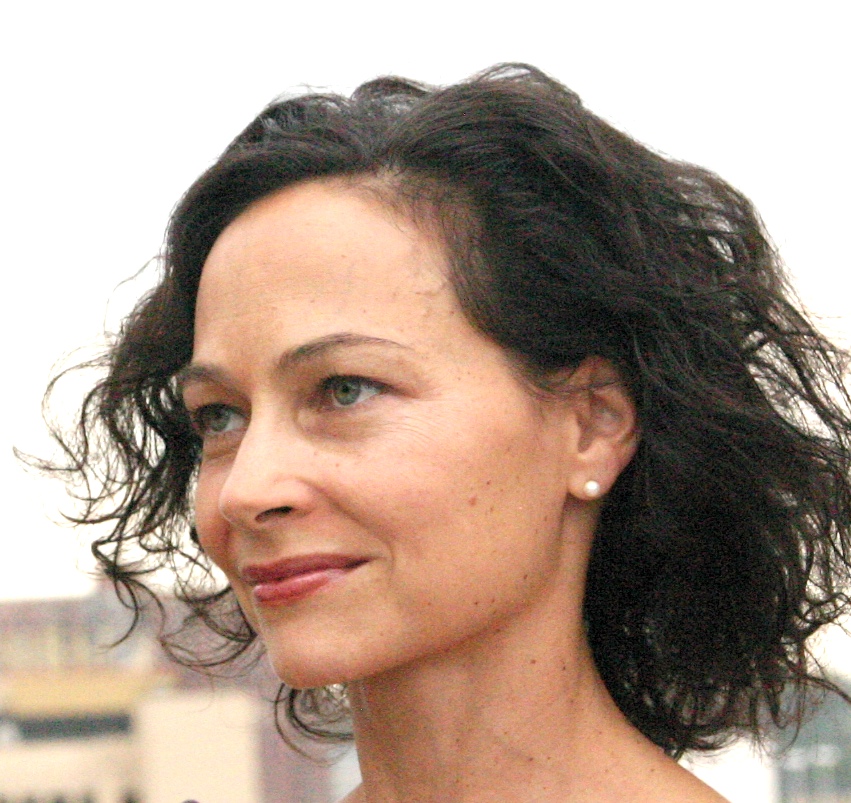

Ballerina Sally Rousse (James Sewell's 20-year partner in dance and life) engages in a sprawling, juicy, utterly fascinating conversation with dance writer Lightsey Darst, in which she reflects on her artistic and personal life as a muse

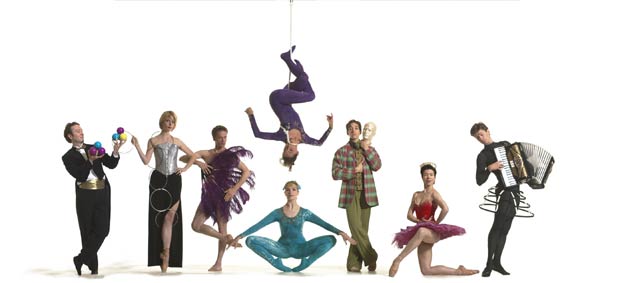

One day in December, right after ballet class, ballerina Sally Rousse stopped me with an idea for an article: would I be interested in writing something on what it means to be a dance muse? It was a topic Rousse was thinking quite a bit about at the time, because she was then separating from her husband James Sewell, for whom she has been an invaluable muse for nearly twenty years. Of course, I agreed. Rousse is a fascinating dancer who has appeared with the avant-garde duo Hijack in addition to her work in James Sewell Ballet‘s productions. And to explore the idea of being a modern-day muse—what a fascinating, even dangerous subject. I wanted to know more.

Shortly afterward, Rousse writes to me about a conversation with a friend, another dance muse. Rousse recounts, “We went into the whole muse thing and it was really helpful to me. I do think it is a topic that might interest the general public, the dance folks, and hopefully you. I am really getting something very good out of talking about this very intimate relationship—the muse/creator thing. I don’t need to go to a negative place about it: it is what it is. (Was what it was. Is it still going on? Who am I?)”

This is typical of her tone: there’s always a brilliant intimacy, transparency, aliveness. If you’ve never seen her dance, this is a fair sample of her dancing as well. First we have to lay some groundwork. We’re all familiar with the idea of a muse—a painter’s muse, a poet’s muse. But a choreographer’s muse is different. For one thing, she’s alive in the work when it’s done, still herself, not abstracted into some other form. Also, “the muse” is a somewhat old-fashioned idea these days, having been used in the past to repress women’s creativity, so I was curious how a modern-day muse would talk about her work.

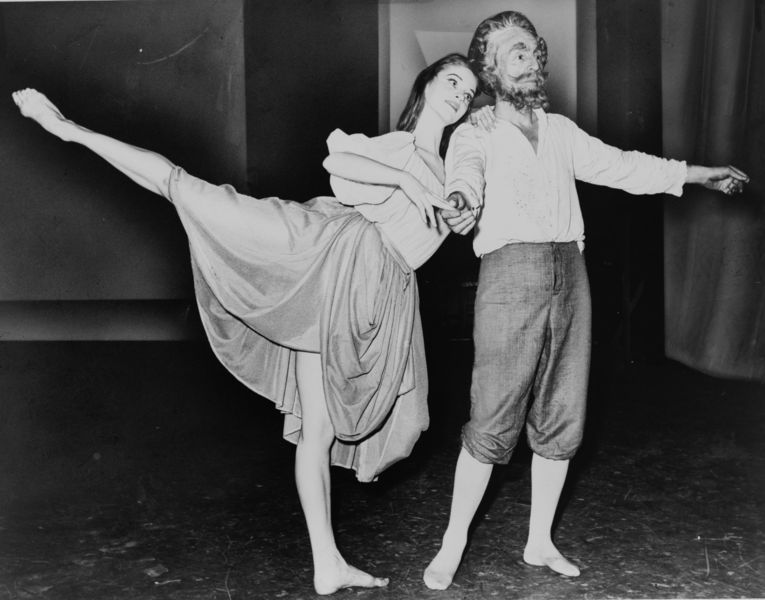

What does it mean to be a muse in dance? And how “official” is this position? That is, is “muse” common parlance in the dance world? Rousse responds, “There is no ‘official’ position of muse. Certainly, [there’s] no title that is ever written in a program or contract, no extra payment monetarily, or any visual symbol.” She goes on, “I think the first time I heard the term was when Suzanne Farrell was on the cover of Time magazine, with an article and photos of her with George Balanchine when his Don Quixote [supposedly created for Farrell] was premiering. I heard my mother talking about it with her Bridge Club ladies. I think I must have been eleven or twelve years old. (It would be another two years before I went to New York, to the School of American Ballet.)”

“My mother’s talk with the ladies had a hushed quality to it,” Rousse recalls, “and there was a hint of gossipy, naughty wonderment about Balanchine’s marriage proposal to Farrell. I remember assuring my mother, years later, that she wasn’t to worry: I would never marry Balanchine, so she should let me go to New York City by myself. And she did! I was 14 when I went.”

“Anyway,” Rousse continues, “I didn’t really understand the muse thing then, but I gathered that it was a special relationship, like being a teacher’s pet. Maybe you would get to be the example of how to dance something, or in some way ‘speak’ for the choreographer who couldn’t really dance anymore. I think that more or less is true. A muse is someone who is an extension of the main creator, someone who can find the mot juste or satisfy some mysterious vision the choreographer has.”

An extension of the main creator: that’s not how most artists describe themselves. But dancers are different, particularly ballet dancers. If the dancer-choreographer has become the dominant paradigm in postmodern dance, it’s not so in ballet, where most dancers are just that.

Rousse goes on, “the Farrell-Balanchine example is, perhaps, the most famous, but others come to mind as well: Valda Setterfield and David Gordon, Carolyn Brown and Merce Cunningham, Margot Fonteyn and Frederick Ashton. But being a muse is certainly rare and not at all a measure of a dancer’s worth or greatness. Not necessary. Maybe not even something to strive for, and impossible to plan, really. It doesn’t need to have romantic love attached to it (though maybe half the time it does). Most well-known dancers were never muses: Mikhail Baryshnikov, Rudolf Nureyev, Gelsey Kirkland, Martine Van Hamel, Natalia Makarova, Anthony Dowell.”

Rousse describes her first muse relationship. “I only became aware that I was Peter Anastos’s muse when he told me so,” she says. “It was surprising, because he could be so hot and cold, and everyone kind of loathed him. I must have done something to please him, win him over; I know I surprised him,—he didn’t think I would be as good as I was, or something like that. It was more in our talking than in my dancing that we got to know each other. One evening at dinner, he said he wished everyone in the company (Garden State Ballet, New Jersey) were like me, and that he loved everything about me. (He’s gay, 150%.) Of course, it eventually changed. He became angry with me when I got a position with another company. But, it was a sweet time. He would ask me to sit next to him during rehearsals of ballets I wasn’t in. He taught me about comedy and how to pass along roles. He made me teach company classes, even though I was one of the youngest. And, like Balanchine did with Suzanne Farrell, he taught me about good food,” Rousse recalls fondly.

Just as a painter’s muse isn’t necessarily the most beautiful person the painter’s ever seen (but perhaps the most interesting), a choreographer’s muse might not be the most technically perfect dancer in the room. I have an embarrassing admission—I only recently saw Suzanne Farrell dancing for the first time, on a Balanchine DVD. She wasn’t at all what I was expecting, and it took me a while to see her. She dances with her body rather than with her extremities, and she’s got a reckless willingness to seize opportunities that doesn’t match with today’s emphasis on precision. Watching her, I wonder whether Balanchine liked the imperfection, the individuality of her performance. There were certainly more uniformly correct dancers in the corps behind her.

Rousse herself studied at one of the best dance schools in America, but that’s not what you think of when you see her perform. While some dancers present their technique and virtuosity to the audience, Rousse dances past hers. “That’s old, we know that,” her movements seem to say. “Where haven’t we been? What haven’t I showed you?”

Rousse agrees that Farrell’s appeal for Balanchine likely lay beyond technical skill. “Balanchine seemed interested in her attack, her spirit, beyond the steps,” Rousse says. “Sometimes dancers think the steps executed precisely will win them respect and love, but it’s more: a giving attitude, a trust, a focus, I think: ‘I will do whatever you say and more.'”

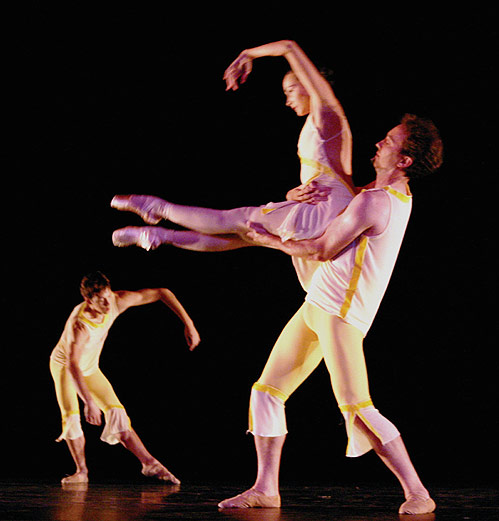

With this, Rousse opens yet another door in our conversation. I follow up on the power balance suggested by the dancers’ attempts to please the choreographer. “The steps, executed precisely, will win them respect and love,” that almost sounds like a parent-child relationship. Does the muse have more power in a relationship with the choreographer than the non-muse dancer? Rousse affirms, “There is some sense of power, definitely. I was not very comfortable with it, mostly. It’s not useful and most of the other dancers hate you because of it.” Along the same lines, she discusses casting. “It has always been important to me to be cast justly,” she says. “And, even though we are an excellent match physically, proportionally, I have gotten James to put us with other partners, so that we can continue to grow and learn with others and so the audience doesn’t tire of seeing us together. I know I have worked hard, but when I’ve seen other dancers, who were either in a relationship with the choreographer or about to be, get leading parts, it kind of puts their integrity into question.”

The next thing she says about the dancer’s power surprises me. “I do think the dancer has quite a bit of power, muse or not,” Rousse remarks. “I have seen and heard of some clever power moves in my day! One dancer feigned injury so that the choreography wouldn’t change to her bad side. A choreographer relies on a dancer’s memory quite a bit so it’s possible to subtly change something, conveniently, for the better or so that it’s more flattering. Because most choreographers are men and I am on pointe, I can choose one of the many ways to get onto pointe if he hasn’t specified. Often he will say ‘Which is best?’ and I get to choose. Or, I show him all the different ways, and he chooses. Isn’t this silly? But I can’t tell you how much time is spent on this little thing. I could choose the easiest way to get onto pointe (pique) but that isn’t me. I would feel guilty. I have to seek the ‘best,’ most pleasing way.” She says further, “I am, of course, no longer meek and shy. But during creation time, I really try to be sensitive and give everything. Not to work my power, even if I can.”

So, the muse may have more power than other dancers, but part of what makes Rousse a muse is the power she relinquishes to the choreographer, rather than the power she wields over him. Talk to Rousse for a few weeks, and you will begin to get a feel for what makes her so attractive as an art-partner. It’s not that she’s easy to understand. Just the opposite is true, in fact. Her compelling difference never quite yields to interpretation. An example: convinced I’d made an empathetic connection with Rousse’s muse-dom and thinking that I would nudge loose an agreement, I wrote her the following in an email: “It sounds as if being a muse is exhausting. That perhaps it calls on you to be something larger/other than yourself, or perhaps some heightened version of yourself, or a particular aspect of yourself. It’s always nice to have space in which to retreat from the world and be empty, be nothing. To drop any kind of grand notions or ideals, to be free of any eyes that perceive you one way or another—particularly if that perception has become a burden, a role to act.”

Contrary to my expectations, Rousse came back with the following response. “I would say that perhaps my place disallowed me to see James for who he is, really. It is a god-like role, choreographer. My role is to trust, to please, to obey, to let go and offer myself, and be vulnerable–brilliant if possible. Not a burden; life, depending on your upbringing. Nothing pleases me more than to know I have delighted someone, that they ‘get me’. It’s the life I have led, and I am pleased to have led it, but I do feel I have sacrificed something, even if I’m not sure what. Nothing I can’t deal with. I think that with James, we have similar bodies, work very well together (he can lift me, I can lift him!) and, yes, that transferred to our personal life. No doubt, neither of us will find a more perfect physical match. But in order to grow, as people, as artists, we’ve needed to jostle it. Partner with other dancers, make dances with others. The dances he makes with Penny (Freeh) he wouldn’t have made with me, and they are brilliant! How he works with Justin (Leaf) is unique and still in an embryonic state. I think James is on the verge of a new creative process: I am not there pushing him, pleasing him, posing questions, any of that. It’s like an old chain necklace that I want to untangle. I’m not going to throw it out—it’s gold! It’s precious, an heirloom!—but the knots are so frustrating that I can’t see how to untangle it, though I know it’s possible.”

In other words, Rousse blames the muse’s view of her choreographer more than the choreographer’s view of his muse for any failure in the relationship between the two. Even now, I know I’m not summarizing this accurately, because Rousse fundamentally can’t be gotten. To be honest, I half fell in love with her after getting this email. It made me want to look at her for the next six months, just because it proved how wrong I’d been. I can imagine a choreographer finding this scintillation unfailingly interesting as well. You think you’ve encapsulated her essence in one piece, but then the next morning you find her in the studio, testing out something utterly different.

An unkind interpretation of her take on the muse/choreographer relationship would suggest that Rousse contradicts herself. I don’t think that’s accurate. Truth need not be linear, as Rousse is keenly aware. Different facets of a life catch the light at different moments.

Throughout our conversations, Rousse never discusses the political implications of being a female muse for a male creator. Instead, she carefully brings up several partnerships in which a man has been a muse (Scott Rink for Lar Lubovitch, Erick Hawkins for Martha Graham), pointing out that the relationship doesn’t have to be about gender. Still, muses are overwhelmingly female, and powerful choreographers in the ballet world are disproportionately male. So, at last, I bring up the $64,000 question: To what extent has this idea been a way for male artists to borrow/usurp/steal the creativity of their muses? Rousse sidesteps that phrasing altogether: “Maybe [choreographers] just get the credit. This why I dislike most reviews: they only talk about the choreographer, not the dancers.”

I try to pin down the question of her creativity, and what had become of it. Rousse choreographs pieces herself, so I attack the subject from that direction. I ask her how being a muse has affected the way she makes her own work. “Not so much,” she replies. “I offer all my movement, and give away the best, the juiciest–everything. That’s my nature. I can generate movement aplenty. It’s not all good. Often not good; what is good? In any case, I just offer forth. Not now to James, of course. I cannot even dance in front of him sometimes these days…. But, still, no regrets—just onward. I’m eager to give to whomever wants, who can put me to proper use.”

Perhaps “muse” suggests that you deeply inspire the work, but it’s not your own creation. So, I ask Rousse, must there be some distance between the work and your instincts? Between the choreographer’s projects that feature you and what you would have made of yourself?

She responds affirmatively, saying, “and here is where problems begin. As I have started to choreograph, to suggest concepts, that has not gone well. [James] takes it and runs with it in a direction I would not. Does different (or no) research, or maybe he does not go into depth. Even so, I have to say, his work has been amazing and it is better when I just keep quiet and don’t judge. Better to be amazed and then go find my own way.” She adds, “But maybe [from now on, I will] not give my ideas away.”

I keep poking at the question because, I suppose, I’m still curious about the fit between a muse’s own creativity and that of her choreographer. “Mostly, we muses don’t choreograph,” Rousse explains. “That is a more contemporary conceit. The [traditional] role of the muse is to offer–totally, blindly, dumbly. And, so, here we are: I cannot be a muse anymore.”

At this point, Rousse suggests I talk to James Sewell, her long-time choreographer and partner, about our musings. Sewell speaks about the muse-choreographer relationship generally. “It’s very beneficial when you have someone who understands” what you want of them, he says, and who can take the work further; someone who “inspires you to want to create things on them.” He goes on to say, “Ideally, your whole company is that.” Sewell suggests that all choreography is collaborative.

So, I ask him, “Does a choreographer need a muse?” Sewell argues that it’s more the case that a choreographer needs a body that can inspire; some choreographers (Trisha Brown, perhaps) find this in themselves. In fact, he says, “you have to be able to be your own muse,” because the fascinating dancer with the great rapport isn’t always around. Sewell has served as his own muse a lot, particularly for his explorations into complex coordination. But “I’m sick of me as a muse,” he bursts out.

I ask him, “Is Rousse a muse because that’s just how she is, or is she a muse because a choreographer (Sewell himself) sees her a certain way?” But the question doesn’t seem to have an answer. Rousse’s protean nature is part of the answer: “I don’t think that there’s something I can imagine that she can’t do,” he says emphatically, paying her perhaps the highest compliment a choreographer can offer. But the rest appears to lie in chemistry. Sewell says, “interesting things would just happen” in rehearsals between Rousse and himself. Why? Because they were intimate? Because Rousse and Sewell, both small and crazy coordinated, were physically a good match for each other? What I gleaned is this: Rousse is an exceptional dancer; what’s most exceptional about her is her ability to take on anything; but she wouldn’t be a muse if a choreographer didn’t need her, and she wouldn’t be a muse if there weren’t a close relationship involved, or at least the possibility of a close relationship.

Now, this is interesting. We hardly ever talk about the give and take of intimacy when we talk about art. We might acknowledge that the creator was inspired by his muse, but we usually assume that the muse is simply a person in which the creator sees something else—a tilted mirror. We need to reevaluate this and apportion some additional credit (as Sewell does) for the work to the muse. But this isn’t all: take the question from the muse’s point of view. What can we say that she contributed? Any language we use is apt to diminish her own creativity: “She was a great dancer,” we begin, “and she gave inspiration to great choreographers.” Plenty of women are enshrined in history as the lovers or muses of famous men. The typical revisionist maneuver is to reallocate credit: she made the decision, she wrote the work, etc. But Rousse’s history suggests we need to invent a new category of achievement, one that mingles creative talent with emotional talent, one that mixes art and life.

And perhaps we should also replace the idea of artist as godlike creator with a more atmospheric sense of artistic creation. Rousse makes just this point toward the end of our long email conversation. With regard to the balance of creative responsibility in dance, specifically on the subject of her own, individual contributions, she articulates a democratic view of dance that startles me. “The steps,” she observes, “are just exalted walking. Extreme, articulated, exquisite walking.”

“You can separate the dance from the dancer—the dumbness of the steps” from what the dancer finds in the steps, she explains. Choreography is not all, or even most, of dance. The human connection is greater. Perhaps this is why critics often find modern productions of Balanchine’s work inferior to the originals, despite the steep ascent in American ballet technique since the ’60s and ’70s: Balanchine and his dancers shared something special. The steps can be repeated, but the dance won’t be the same.

Similarly, she says, “whatever I had with James can’t be repeated,” she says, but not sadly. She believes that he muse moment, no matter how long it persists, eventually fades, and she tells a story to back up this idea: Balanchine and Suzanne Farrell are in the studio. He asks her to just show him something; she pops into a deep arabesque on pointe. “No, not that, I’ve seen that before,” he says. So Farrell does the step again, but this time with a little twist at the end. So, Rousse says, there was just “a little more he was wringing out of her.” And after Farrell married another dancer, breaking up any potential romance with Balanchine, “she was never his muse again”—at least not with the same intensity.

If Rousse has rejected her own muse-dom for now, she hasn’t rejected the idea itself as some outmoded Old World concept. And it’s hard to resist the idea that Rousse will be a muse again, simply because that’s the way she dances, the way she works. But for now she wants independence. “I will work with other people now, other than James,” she says. “Judith Howard, Hijack, Lisa de Ribere (New York), and whoever wants me that I find sympatico. No romance.”

Our conversation never did end, from my perspective; it just opened up new questions. What is a dancer, and how should we recognize and talk about what dancers do? Is there an artistry of personality, an artistry of relation? Towards the end, Rousse talked about Sewell again—but about her choreographing work for him—a flip that seemed to excite her with its troubles and its rewards. “I love to see him realize my visions,” she says.

Rousse has long been a dancer I’ve followed, one to watch. Before speaking to her about the muse question I’d never bothered to locate what it was about her that compels me. It isn’t that I love her choreography; it’s more an instinct I have about her. In fact—and this may be a perfect example of Rousse’s hard-to-grasp artistry—my favorite work of hers is one I’ve never seen, her aerial piece trickpony (created with Chelsea Bacon). I first felt the piece as a form within Rousse and Sewell’s larger ballet Awedville, which occasionally showed its sharp corners through Sewell’s rounder choreography.

I’ll let Rousse have the final word on the muse’s complex life: “There is an email (that neither of us can find) I wrote a friend in the fall, when I first thought about how it feels to struggle in my feelings, with my muse-dom! [In it] I said something I like, honest and big: ‘it’s been an intense, complicated time of beauty, trust, stress, loyalty, sexuality, power, and friendship.’ I know that’s not it but that’s the best I can do.”