The Seer of Red Wing: The Art of Charles Biederman

Glenn Gordon, who has been documenting the work and life of Charles Biederman, reviews a small retrospective of this eminent Minnesota artist's work: "Charles Biederman: An American Idealist," at the Cedar Rapids Museum of Art through March 16.

introductionCharles Biederman has created a body of work and theory that single-handedly propounds a certain world: defined by light and color; full of incisive choices; devoid of most issues thought important by the artworld and its texts for the past 30 years. This work has survived (but in some senses barely); he has survived, aesthetically and spiritually as well as physically, through his total investment in his extraordinary work. Biederman’s outsider status gives his pieces authority as visual documents, divorced as they are from the strategies and rhetorics of work done inside the artworld. Glenn Gordon here delivers a ringing call for reassessment of this survivor’s rich body of work.

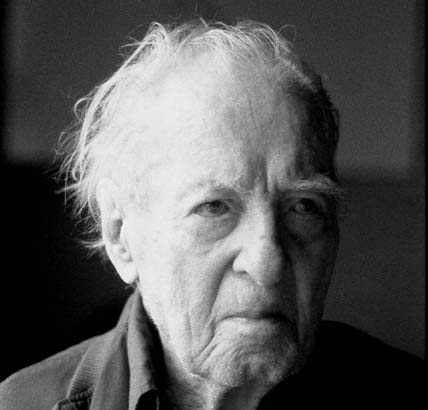

Charles Biederman has created art of a high order over a longer span of time than most of us have been alive. Contemporary critics and art historians seem to regard his art as dated; they relegate him to the realm of the safely dead. Biederman, now 96 years old, frail, and almost completely blind, is nevertheless still among the quick down in Red Wing and appears to have no intention of dying until he’s damn well ready.

Neither does his work, which is magisterial. I believe it will outlive us all. If you’re sick of religion and of art that has nothing to say, I’d suggest a drive some Sunday down to Iowa and the Cedar Rapids Museum of Art for an afternoon’s contemplation of the museum’s current exhibition, “Charles Biederman: An American Idealist.”

The exhibition, which runs through March 16, expands slightly on a small show given to Biederman by the University of Minnesota’s Weisman Art Museum in 1999. Given Biederman’’s prodigious output, this travelling edition of the show, 54 works–drawings, paintings, and constructions in wood, stainless steel, and painted aluminum–is far too limited. It is, though, a step toward the kind of attention Biederman deserves: an international retrospective many times this size, one that fully acknowledges his importance to the evolution of modern art.

Famously contentious, Biederman hasn’t done much to make things easy for himself, often sabotaging his chances for gaining wider understanding by indulging a compulsion for issuing sweeping denunciations of the art world of Paris and New York as “all washed up and phony.” The fallen world of dealers, curators, critics, and ex-patrons has reciprocated by writing him off as a crank, unfortunately dismissing at the same time a body of intensely beautiful work that makes a case for Biederman as perhaps the greatest receiver and transmitter of the realities of color and light that this country has produced–contrary to the show’s title, its most uncompromising realist, a deeply devoted student of the ways of our Mother, Nature, which is to his mind the only thing at all real.

But see for yourself. The show in Cedar Rapids is hung more or less chronologically. As a young man, Biederman worked his way through the succession of isms that described the emerging art of the twentieth century before arriving at the signature style of his mature wall reliefs from the 1960s on. The first of the show’s four galleries exhibits his gifts as a classical draftsman and easel painter before his turn to abstraction. Among the works are a pair of beautiful drawings of female nudes, a large, haunting oil of a woman that owes something to John Singer Sargent, and several self-portraits of the artist in his twenties, one of them particularly riveting through its imperious glare. Some are done in the manner of Cezanne (whom, along with Monet, Biederman reveres above all other artists except da Vinci); others carry overtones of Braque, Kokoschka, Modigliani.

Living in the ferment of Paris in 1936 and ’37, Biederman knew many of the artists who are now the stuff of docents’ guides, among them Arp, Brancusi, Pevsner, Vantongerloo, Delauney, Giacometti, Kandinsky, Leger, Miro, and Mondrian. During this period he made forays into cubism, futurism, and mechanistic and biomorphic surrealism, in works that sometimes outshine those by the inventors of these styles. They illustrate how quickly Biederman apprehended and mastered the succession of experimental modes in the air at the time. The second and third of the show’s four galleries are hung with pieces from this period and a few of Biederman’s earlier “Structurist” constructions from the 1950s.

The last gallery of the show silences the mind. An austere white room, long and narrow, with the atmosphere of a chapel, contains five of Biederman’’s brilliantly colored late wall-reliefs, cascading like music into three dimensions. Each of these is isolated over a white-painted plinth that suggests an altar for the sacrifice of the unwillingness to “open your eyes”—a phrase of Leonardo’s that Biederman often quotes. The works are not lit as Biederman intended (he preferred natural light that changes with the sun’s transit across the sky) but the art in this room, by this master of color, light, and space, a visionary now as blind as his beloved Beethoven was deaf, gives meaning to the word “seer.”