Of Transgenic Petunias and Glow-in-the-Dark Bunnies

Camille LeFevre offers some historical context for the "Edunia" and breaks down the thorny issues raised by the eagerly anticipated unveiling of bio-artist Eduardo Kac's latest creation, a "plantimal" hybrid combining his own DNA with that of a petunia.

BACK IN 2006, I WAS ASSIGNED SEVERAL ARTICLES on what we thought was a soon-to-open exhibition, Eduardo Kac’s Natural History of the Enigma: we were eagerly awaiting his unveiling of a new form of bio-art.

Kac is a Chicago-based “bio-artist” known for his provocative and controversial fusions of biotechnology, art, and genetics. The two-part exhibition was to include both a transgenic petunia — meaning it would combine a gene from Kac’s own blood with a plant gene — and a public sculpture, representing both the plant and human gene proteins, that would be erected outside the Cargill Building for Microbial and Plant Genomics on the St. Paul campus. While the sculpture went up in short order, the petunia project stalled for several years (but more on that later). Here we are in 2009, and Kac’s Natural History of the Enigma, at last, opened at the Weisman last month. After all the anticipation and hype, when you finally lay eyes on the culminating installation, it’s tempting to sigh and say, “Well, that was anti-climatic”– particularly if you’re familiar with Alba.

Alba is Kac’s GFP (green fluorescent protein) bunny, an albino rabbit whose DNA was spliced with a jellyfish protein so, when illuminated with blue light, she glows lime green. Kac’s 2004 show at the Weisman, gene(sis): contemporary art explores human genomics, included photographs of Alba (but not the actual rabbit). Mary Abbe’s article about that exhibition for the Star Tribune hit newsstands with the splashy headline, “A potent show comes to the Weisman Art Museum;” the Star Tribune piece also reported on a number of comments left in a guest book of viewer responses to Kac’s bunny: “‘There are some times when technology can go too far. Why should we mess with something so naturally beautiful as life?'” Another visitor to the exhibition reportedly condemned the project as “sick” and asked, “How is this OK? How is combining a jellyfish with a rabbit OK? Please don’t try this again — or anything like it.”

Though people were gazing at a photograph of Alba rather than the actual rabbit, the mere image of such reproductive cloning was enough to “activate the deepest phobias about mimesis, copying, and the horror of the uncanny double,” as W.J.T. Mitchell writes. Mitchell is referring to the unsettling experience Sigmund Freud identified as the sensation that occurs when something familiar is repressed, only to return in an uncanny or unusual form — say, a common pet-shop bunny that glows green. In the chapter “In the Age of Biocybernetic Reproduction” of Mitchell’s book, What Do Pictures Want?, the author also argues that biocybernetic reproduction, which he defines as “the combination of computer technology and biological science that makes cloning and genetic engineering possible,” has “replaced Walter Benjamin’s mechanical reproduction as the fundamental technical determinant of our age. If mechanical reproducibility (photography, cinema, and associated industrial processes like the assembly line) dominated the era of modernism, biocybernetic reproduction (high-speed computing, video, digital imaging, virtual reality, the Internet, and the industrialization of genetic engineering) dominates the age that we have called postmodern.”

Alba’s likeness — not to mention her very creation — upset people because she “goes before us as a figure of our future, threatens to come after us as an image of what could replace us, and takes us back to the question of our own origins as creatures made ‘in the image’ of an invisible, inscrutable creative force,” Mitchell writes. Contained within Alba’s image, then, are religious subtexts of sins of both idolatry and audacity, transgressions committed through the god-like creation of beings whose existence lies outside of the normal bounds of nature.

________________________________________________________

Kac’s creations “go before us as a figure of our future, threaten to come after us as an image of what could replace us, and take us back to the question of our own origins as creatures made ‘in the image’ of an invisible, inscrutable creative force.”

________________________________________________________

On the other hand, true to the spirit that drives the capitalist/consumer impulse to industrialize and commodify the products of biogenetic engineering, one of Alba’s fans requested a version for himself: “‘Where did you buy the glowing bunny? ‘Cause I want one,'” Abbe reported in her article for the Star Tribune.

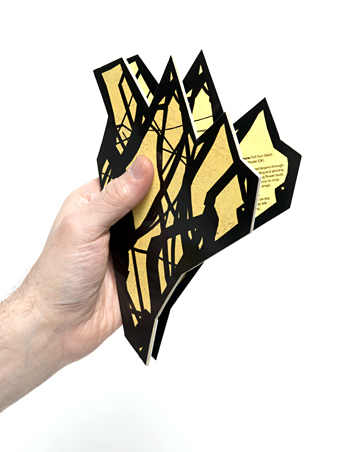

It’s doubtful that Kac’s petunia, or “plantimal” as he calls it, will elicit similarly heated reactions, simply because there’s nothing immediately uncanny about it. The flower looks like an ordinary, garden-variety, plant hybrid. For that matter, “Edunia,” as the artist has dubbed his creation, does display hybrid vigor: it’s a bushy plant with healthy, thick, slightly fuzzy deep-green foliage and a profusion of pink, frilly, petunia-like flowers. If placed next to its cousins at the garden store it would probably be tagged as “America’s Best” or “Premiere Selections.” Spoofing this line of thought, Kac has included in the exhibition designs for a proposed seed packet. “Superb garden performance” reads the Edunia packet, which is shaped and folded to resemble the yellow and black wings of a swallowtail butterfly (as if Edunia’s propagation actually relied on natural selection, rather than the methodical efforts of laboratory technicians). In our ocularcentric culture — where the visual is inextricably interwoven with media buzz, industrialization, desire, and commodity fetishism — bioengineering a new life form in which the Frankenstein factor isn’t obvious actually seems counterproductive.

That’s not to say that Kac and his team didn’t try for a bit of hype.

In 2003, after Kac approached University of Minnesota plant scientists about helping him create a flower that would express his DNA, Dr. Neil Olszewski, a professor of plant biology, stepped up. In order to fully express Kac’s blood protein, they decided to fix a broken sequence in a mutant white petunia, in hopes of producing a white flower with blood red veins.

Olszewski and his staff got a sample of Kac’s DNA, sourced the correct protein gene, recreated it as a synthetic, then stitched it together with the plant gene that would express Kac’s in the plant’s veins. The project was a bust. So the team took a less dramatic approach. “We decided to start with a petunia that already has red veins,” Olszewski explains. In Edunia, Kac’s gene is visible under a microscope, Olszewski says. But to the naked eye Edunia “looks like a normal petunia. The trans-gene has had no effective on the plant’s appearance.”

With bio-art, however, Mitchell argues, the “object of mimesis here is really the invisibility of the genetic revolution, its inaccessibility to representation.” As such, the work “dramatizes the difficulty biocybernetic art has in making its object or model visible…. one is basically taking it on faith that the work exists and is doing what it is reported to be doing.” In many aspects, then, the real subject matter surrounding bio-art and biocybernetic reproduction, according to Mitchell, is “the idea of the work and the critical debate that surrounds it as much as its material realization.”

And the sculptural portion of Kac’s Natural History of the Engima was, in its initial conception anyway, no exception; right away it provoked an argument about conflicting academic freedoms among scientists and the bio-artist.

According to a 2004 University of Minnesota “Report of the Task Force on Academic Freedom,” Kac’s “concept in combining a human gene with one from a plant recognized and honored the long relationship that humans have had with plants-and of course was meant to represent the kind of research that goes on in the building.” Precisely for that reason, some of the plant scientists balked. They had security concerns. Their work is legal and ethical, but they felt threatened by the possibility that Kac’s sculpture would encourage problems with “people who see genetic research of any kind as meddling with nature.” Ultimately, the academic researchers working inside the building, Kac, and the university’s public art committee compromised on a “plan in which the artist agreed to make certain changes to his use of genetic material which made the project less objectionable.”

What were those changes, I wonder? Was one of them reflected in the decision to opt for a red-veined petunia that would hide the expression of Kac’s DNA from the human eye? And yet, in spite of those early concerns, there is a fiberglass and steel sculpture, the monument to Kac’s Edunia, in residence outside the Cargill Center. The helixes on the left side portray the protein transcription factor that controls pigment in flowers; the vertical forms on the right represent Kac’s protein.

As such, the bright orange sculpture encapsulates, albeit abstractly, the fusion of human and animal; and in so doing, it unavoidably poses questions about the relationship between human interference in the natural world and the truisms propagated by some of humanity’s oldest belief systems, about the creation of life and the role of art to reveal and expose our evolving capabilities — imaginary or real — in the age of biocybernetic reproduction.

Exhibition details:

You can see the gallery installation, Natural History of the Enigma, at the Weisman Museum of Art in Minneapolis through June 21. The fiberglass and steel sculpture commemorating the Edunia project, Singularis, is part of the Weisman’s permanent public art collection and will reside indefinitely in front of the University of Minnesota’s new Cargill Center for Microbial and Plant Genomics.

About the author: Camille LeFevre is a St. Paul-based arts journalist, dance scholar and communications strategist. Please visit her website at camillelefevre.com.