Numinous Anomalies: Somali Visual Art in Minnesota

An emphasis on connection—between Minnesota and Somalia, artist and community—is key for "Anomalous Expansion," as is claiming authority, says critic Christina Schmid of the landmark exhibition of work by six artists currently at the Darul Uloom Islamic Center in St. Paul.

Nestled in the Dayton’s Bluff neighborhood of St. Paul, Darul Uloom Youth, Family, and Community Center shares its name with the mosque next door, the former St. John’s church. Far off the beaten tracks of the Twin Cities’ art circuit, I am here to see Anomalous Expansion, a group exhibition curated by Mohamud Mumin and the first of its kind to bring together visual art created by six Somali American artists. Following spray-painted signs in the hallway, I climb the stairs and find the first of four rooms (and a rooftop!) turned temporary gallery. Suddenly, I am surrounded: a group of boys, young teenagers, bustle through the gallery. “Don’t touch it,” they tell each other. “It’s art!”

When Mumin, whose visual storytelling has gained local and national recognition with projects such as Dhallinyarada/The Youth and Xusuus Sahmis/Scouting Memory, first saw the building, “the space asked us to do this,” he says at the panel discussion about the show. In order to get permission to use the building for what the handsome press release (designed by Kaamil Haider) calls “a landmark exhibition,” the artists agreed to abide by Muslim articles of faith: no figurative painting is included. “Creating a figure means doing god’s work,” Mohamed Hersi explains to me. For Hersi, that meant a departure from his usual creative practice and challenged him to explore new artistic terrain in a series of untitled abstract paintings. If at first glance such compromise seems to signal a form of voluntary censorship, it bears remembering that similar gestures in other institutional settings have been applauded for the respect they convey. At the Minneapolis Institute of Art, a recent exhibition left a vitrine intended for a Native American artifact empty to convey respect for the beliefs of its makers and culture of origin.

The title, “anomalous expansion,” refers to the strange chemistry of water: rather than lose volume when its temperature drops between 4 and 0 degrees Celsius, right before freezing, it expands. This anomaly results in ice initially forming on the surface, starting with a thin sheet of ice that protects the aquatic life below. Mumin, a University of Minnesota alum with a degree in chemistry, sees Anomalous Expansion as a metaphor for the flourishing of the Somali community in Minnesota. Besides, the vocabulary of visual art literally expands the traditional forms of Somali culture, whose rich history is on display at the Somali Museum of Minnesota in Minneapolis, an institution eloquently represented by Osman Ali at the opening reception. There, artifacts from Somalia are gathered and preserved. But, as Haider puts it, a culture risks becoming stagnant if it only looks to the past. Such conservatism is a well-documented phenomenon among immigrant communities across the globe, likely to occur whenever and wherever a cultural community fears for its survival. Thus Anomalous Expansion signals the health of the community: the artists balance reverence for their Somali roots with an appetite for new forms of expression.

Even two years ago, says Ifrah Mansour, a multimedia performance and installation artist, the idea of showing her artwork in a space like Darul Uloom (which means “House of Knowledge”) was inconceivable. “East Africans were not there yet,” she remembers. “They were not valuing art.” Contemplating what has changed, the artists acknowledge the education necessary to familiarize their community with the strange, contemplative rites and participatory practices of contemporary art. In the catalog that accompanies the exhibition, Mumin emphasizes the goals of normalizing “the possibility of a career in the visual arts for Somali youth,” offering role models, supporting policies that will advance and support Somali visual arts, and creating opportunities for Somali artists to show their work. Community, then, plays a central role in the conceptual framing of Anomalous Expansion.

Anomalous Expansion signals the health of the community: the artists balance reverence for their Somali roots with an appetite for new forms of expression.

Yet the continuous pressure to educate can be tiring, too, says Mansour. On the one hand, the artists find themselves advocating for visual art in their community; on the other, outside audiences fall into the problematic habit of expecting to be educated, too. Artists outside the white Euro-American mainstream are still much too often treated as spokespeople for their respective communities, their art relegated to an exclusive representational space that forecloses what their work is allowed to say, do, and mean. A degree of explanatory fatigue is no surprise.

But while such context matters — and the curator’s text clearly argues for the exhibition’s significance in terms of community — there is the artwork itself. And unlike other recent community-oriented art projects that seek to find novel ways to encourage participation, interaction, and engagement, Anomalous Expansion relies on firmly established genres of the Euro-American canon: painting, sculpture, photography, video, and installation.

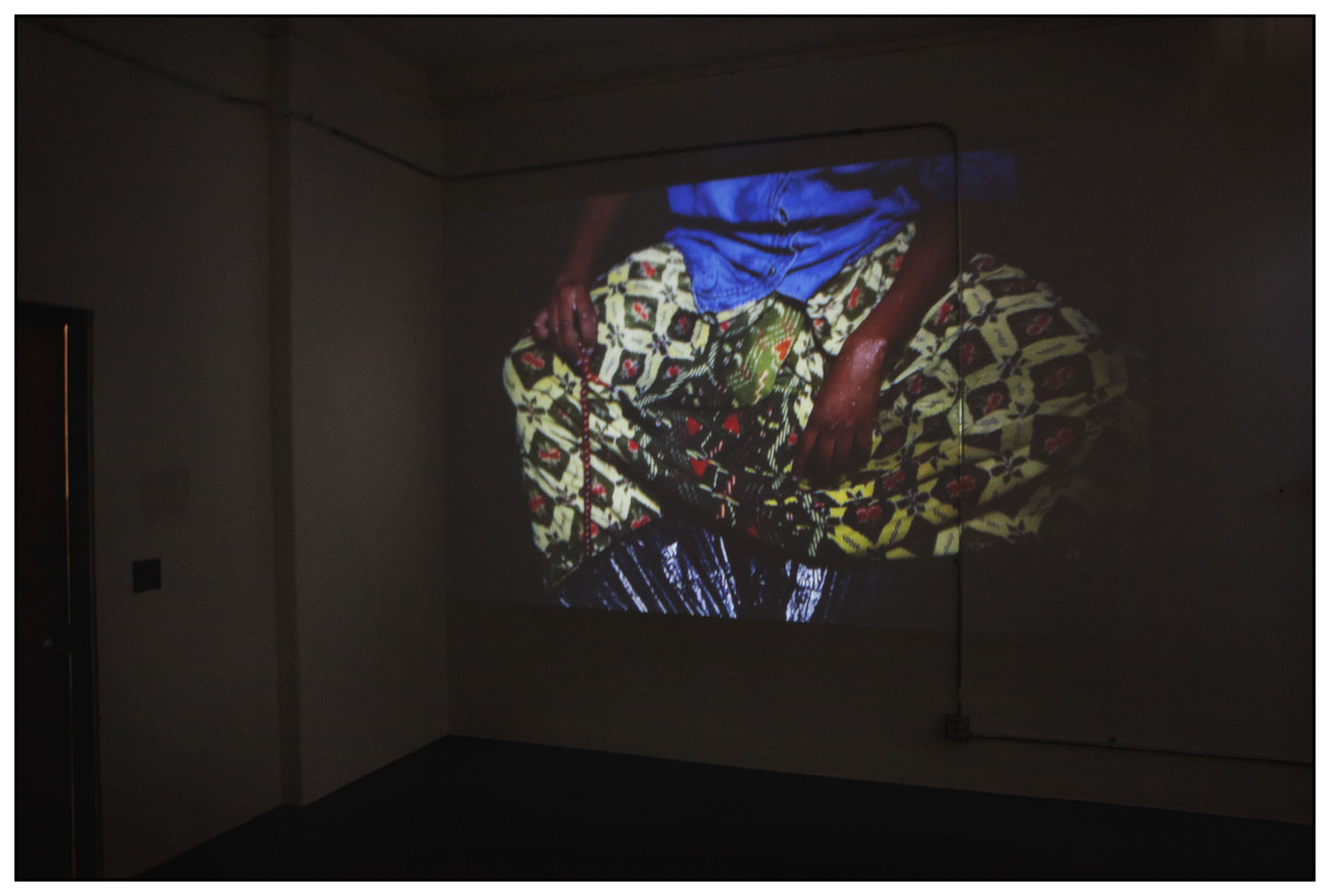

Mansour’s Isug (Wait) combines two film projections: one on a wall, where a woman, dressed traditionally, kneels facing viewers; the other on the floor, where a pair of hands lets go of a series of objects, among them a carved wooden spoon, a woven basket, a ceramic teapot, and a bowl. Briefly, the floor scene changes to a raft being pulled across water and an aerial view of a tree-flanked river. Then, the loop resumes. Hands and objects re-appear. The gesture is multivalent: are the objects being released, passed on, or abandoned? Who is waiting for whom here? In her live performance, the artist interacts with the two projections, observing the objects and moving through the space of passage.

Abdi Roble‘s black and white photographs are similarly concerned with passage. For years, he has been documenting the Somali diaspora. He captures moments of ordinary life in places ranging from the desert expanse of Kenya’s Dadaab to domestic scenes in Anaheim, CA, and Columbus, OH. But more than tracing the displacement of his people, Roble’s work is concerned with the passing of knowledge, whether “divine or corporeal,” as the wall didactic states. The photographs aim to participate in the transmission of knowledge.

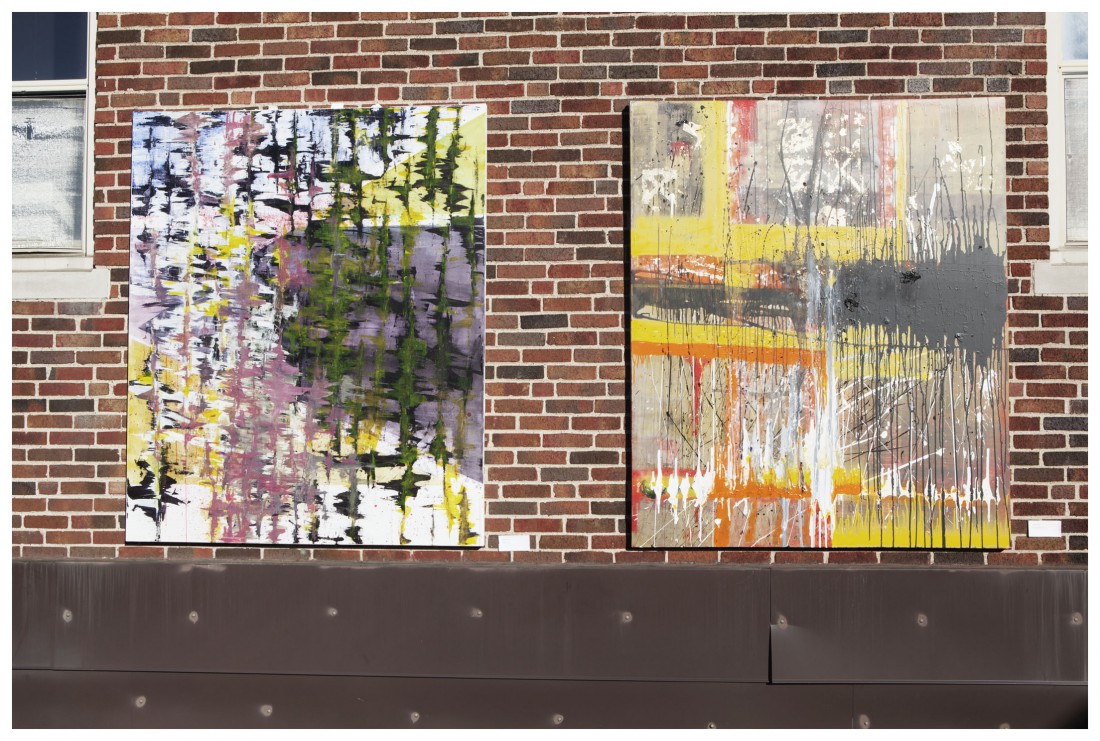

The theme of passing on traditional knowledge re-appears in Kaamil Haider‘s videos. In Gaafow (Camel), two women use long staffs to beat grain. A recording of the artist’s mother singing a song from her childhood accompanies the rhythm of their work. Tradition meets religious practice in Equanimity, where a man makes wudu, that is, performs the ritual ablution before prayer. The work is quiet and focused, in keeping with its subject. Mohamed Hersi’s abstract paintings, on display on the rooftop, also relate to prayer: on five canvases, he harnesses the language of abstraction to represent the chaos and frenzy that rise in the mind between Islam’s five daily prayers. “Prayer grounds you,” he tells me. The titles of Aziz Osman‘s colorful resin-on-canvas abstractions allude to states of mind, too: Oasis of Calm, Dream, and Delirium are a case in point. Hersi’s and Osman’s use of abstraction may not fit neatly into the language and history of European and American abstract painting, but then, who is to say that this idiom should not be hybridized, recontextualized, and translated?1

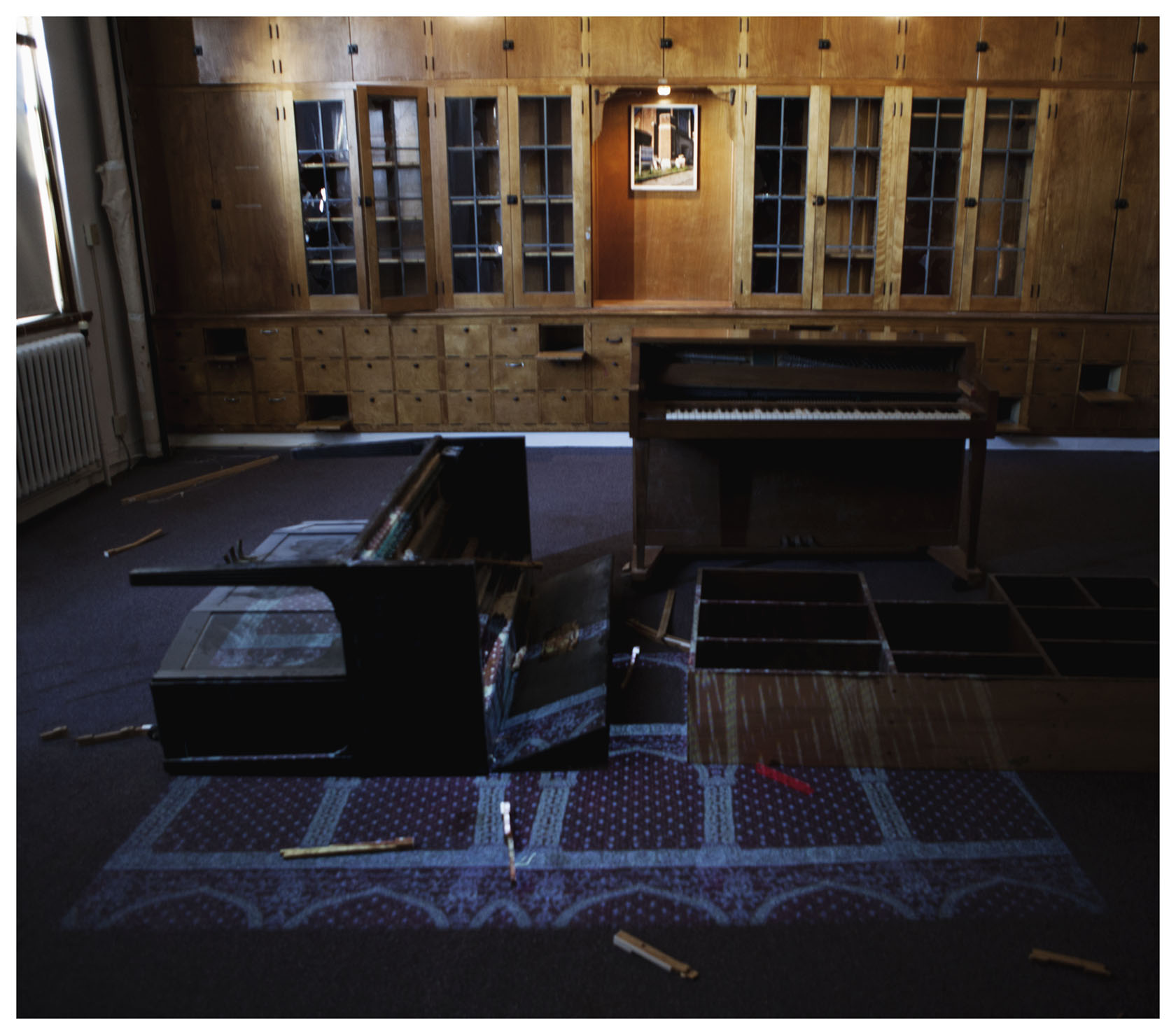

Mohamud Mumin’s site-specific installation Al-Fûtûhàt al-St. Paul (The St. Paul Openings) extends the art’s dialogue with Darul Uloom. In a room scarred by vandalism and neglect, broken glass, splintered wood, and dismantled sinks clutter the floor. Bright pieces of lego hint at past play, echoes of laughter. A single light bulb illuminates a photograph of the House of Knowledge next door. The only other source of light casts an intermittent glow on the center of the room, where three objects sit: two pianos, only one of them upright, and a toppled-over bookshelf. The projected image, a photograph of the prayer rug that covers the floor of the mosque next door, interacts with the ornamentation and letterforms on the fallen piano, transforming the compromised musical body into something else — a promise, a memory, an anomaly. The spectral image comes and goes, as if to breathe a kind of life into this aftermath of destruction.

Artists outside the white Euro-American mainstream are still much too often treated as spokespeople for their respective communities, their art relegated to an exclusive representational space that forecloses what their work is allowed to say, do, and mean.

At the back of the room, a black curtain creates a small chamber. A similarly veiled space divides the mosque next door to allow women and men their separate spaces for prayer. In the Quran, the veil first appears as an architectural feature (verse 33:53), shielding the bridal chamber at the prophet Muhammad’s wedding from guests and offering a protocol for interacting with the prophet’s wives. But the veil also takes on broader symbolic significance: it stands for the darkness of materialism, ignorance, lies and pretenses.2 In Sufism, the mystic branch of Islam, believers become brides of god who strive to see beyond such veils. In Al-Fûtûhàt al-St. Paul the heavy drapery shields and shelters three thin, black, elongated objects from the space of ruin. They lean against the wall, illuminated from behind. The strange trinity glows in a darkness so rich and palpable it almost becomes a thing of its own. The space, both intimate and unsettling, conjures an abstract architecture of transcendence.3 When Anomalous Expansion ends (on October 8), Al-Fûtûhàt al-St. Paul will travel to Public Functionary. It remains to be seen if a change in context alters the peculiar profundity of the work.

From sheets of ice floating on mysteriously expanding bodies of water to the numinous anomalies of veiled spaces, the exhibition is a fascinating intersection of art, faith, and community. “When it rains in Minnesota, people in Mogadishu open their umbrellas; when it rains in Mogadishu, people in Minnesota do,” says Nurrudin Farah at the opening. This emphasis on connection, between Minnesota and Somalia, artist and community, is key for Anomalous Expansion, as is claiming authority: the artists profess their collective understanding of the importance of owning all facets of the creation and presentation of their art. Steeped equally in the legacies of post-colonial thought (Mumin mentions Kenyan author Ngugi Wa Thing’o’s influential 1993 Moving the Centre as a reference) and in artists’ institutional critiques of the power relations in the art world, Anomalous Expansion opens new doors to much needed dialogues. “Art is an act,” says Mumin, “that sends out ripples.” Impossible to predict where those ripples might go.

Anomalous Expansion features work by Abdi Roble, Aziz Osman, Ifrah Mansour, Kaamil Haider, Mohamed Hersi, and Mohamud Mumin, and the show is on view September 17 – October 8 at Darul Aloom Islamic Center (second floor of the school building), 977 E. Fifth Street St. Paul. Gallery hours are 4 – 9 pm, Saturdays and Sundays. Find out more on the exhibition website: www.anomalus.org