Nine Months in America: Unassuming Grandeur

Suzanne Szucs reviews Wing Young Huie's photo show "Nine Months in America: An Ethnocentric Tour" at the Tweed Museum in Duluth through March 27. The show started at the Minnesota Museum of American Art.

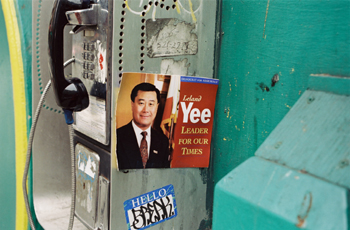

Wing Young Huie has finally come home to Duluth. Considering that the Tweed Museum of Art was the first museum he ever visited, it is fitting that he should bring to it a new body of work that explores the world on a more personal level. This large exhibition of over 120 color and black and white photographs loosely traces the impact of Asian-Americans on greater American culture from Wing’s and partner Tara Huie’s perspectives.

Huie is known as one of the Twin Cities’ most respected street photographers. His projects “Frogtown” and “ Lake Street USA” are inclusive celebrations of those communities. Trained as a journalist, Huie has largely sought out his own photographic education, devouring the style and aesthetics of the greats before him. He has learned his lessons well, incorporating the skill of each of his mentors. His photographs have the spontaneity of Gary Winogrand, the compositional skill of Robert Frank, and the intimacy of Diane Arbus. Most phenomenal is his ability to get into people’s lives. There is a proximity to many of his subjects that even great street photographers shy away from; he’s on porches, in living rooms and bedrooms, with the viewer often left to wonder how he got inside.

Perhaps it is Huie’s unassuming nature that allows his subjects to trust him, which makes this current project his most interesting and most problematic to date. With his previous work, Huie has turned the camera on his subjects in a relatively objective way. We are pulled into their environments and lose track of the photographer. If Huie remains in these images, it is the presence of an empathetic recorder; his vision is positive in a way that differs from many of his predecessors. Huie celebrates his subjects; he rarely criticizes.

9 Months in America marks a turning point for Huie. Immediately it is clear that he’s not only an observer; this project records his experience. This approach is more satisfying to view. It also creates more problems in his presentation.

The disparate nature of these images demonstrates the vastness of his visual excitement about the world before him. At times it feels scattered, like he’s finding his way, finding parts of himself. There is an extremely strong point of view here that is sublimated in his earlier work. We are conscious of where he is standing and what he is seeing. But he can lose focus in the multiplicity of styles and approaches, leaving the viewer stranded. His narrative is definitely not linear and getting sidetracked is easy. He needs to control his vision for the viewer, temper his excitement. Just as the viewer craves his experience, they also need his discipline.

Ostensibly the exhibition is about finding signs of the Asian-American experience within dominant American culture. Perhaps the truly important part of the exhibition are those moments of punctuation that exist in contrast to the more grand gesture… a pile of cut logs, a cloud filled with telephone wires, a car left on the side of the road. Giving us insight about what he is seeing, thinking, these are the moments of Huie’s reflection and they place us within his personal experience of the journey. But these moments can also be disorienting for a viewer when so much else is going on.

It must be a revelation to Huie to look at these photographs. Many photographers pursue self-portraiture earlier in their careers, turning the camera on themselves. They emphasize a physical presence. But Huie’s self-reflexive approach is sight: what he sees describes who he is, and many of these photographs have a strong physical presence, as if made from the body rather than the head. There is also a sense of greed here, as if one focus is not enough. Some of the images therefore become compound – a straight line of cement leading up to a sword player, a woman in blue contrasting with the landscape. That sense of edge and movement that suggests the photograph is bursting out of itself is exciting.

Huie compounds the busy-ness of his exhibition even more by combining both color and black and white photographs. In the gallery on opening night, I overheard two viewers looking at the work: “Black and white photography is much nicer than color… it’s more demanding.” I couldn’t disagree more (of course I must add a disclaimer that I am a color photographer). There is an urgency to color photographs that is suitable to this material. It is more full and complicated, more difficult to tame, as color is a compositional element that challenges form for consideration.

The Photo-Secessionists (Steiglitz, Strand…) and then Roy Stryker (leader of the FSA photographic team) were early proponents of Black and White photography as being closer to true photographic form. Later, color would be so closely aligned with commercial and amateur photography that an artistic hierarchy was created, with black and white firmly ensconced at the top. Few people realize that there were color images made during the Great Depression. They were seldom shown because they looked too vibrant at a time when the propaganda machine was trying to stimulate compassion. Contemporary photographers embrace color for its heightened sense of reality and, indeed, it can be emotionally demanding, especially when used in journalism.

Huie’s color photographs have a sense of life that is cooled in his black and whites, which are more formal and contemplative. To put them alongside each other can be jarring, especially considering that there is even more to this exhibition: text pieces and a DVD of interviews made by his partner Tara Huie. There is so much in this show that if you go to see it– and you should see it– give yourself plenty of time, or plan two visits.

When asked what this project is about, Huie has said, “…what I chose to see, about me, about America.” That’s a long, tall order, true but a little evasive, also. As artists, we are the guides for our viewers; we take them along on our journeys. We promise to create context for them and they, in return, celebrate our self-indulgence. Huie has offered a vision of himself through the images he has made. It is not yet a concise portrait; it needs more direction, more precision. I imagine, however, that the true importance of this project for Huie the artist will be infusing subsequent projects with this deeply personal vision.