Meat: A Slice of Life

Camille LeFevre muses on the art historical phenomenon of the "meat dress" - from Jana Sterbak to Lady Gaga - and in the process, stumbles upon striking and sometimes personal insights into the intersections of flesh, food, family, and femininity.

LAST MONTH, I PERSUADED SEVERAL OF MY ARTS JOURNALISM STUDENTS to join me in viewing Czech-Canadian artist Jana Sterbak‘s infamous meat dress, Vanitas: Flesh Dress for an Albino Anorectic, at the Walker Art Center. The simple sleeveless sheath, stitched from 60 pounds of flank (or skirt) steak by Walker assistants in 1994, is part of the ongoing Midnight Party exhibition. Sterbak’s 1987 original, 50 pounds of by-now well-cured flank steak stitched into a similar dress pattern, but with a draping cowl-neck, resides in the collection of the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris.

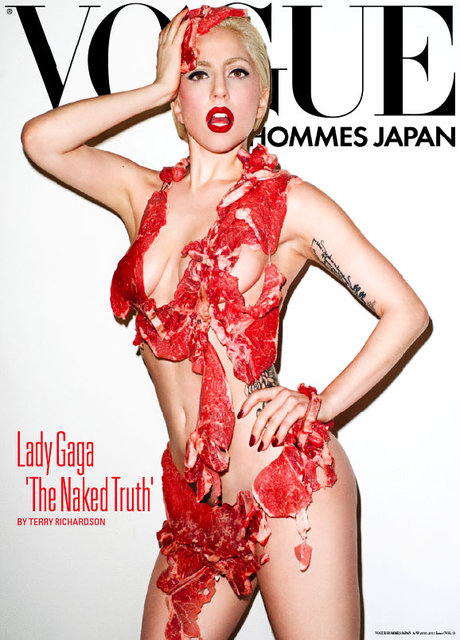

Throughout the semester I’d reminded my students, enticed and appalled as they were at Lady Gaga’s short, ragged-hem version (with meat accessories), worn during MTV’s Video Music Awards in September, that Gaga’s flesh dress was not a new idea (appropriation and innovation in art were among our themes). And I wasn’t referring to Gaga’s prior modeling of a meat bikini for Vogue Hommes Japan.

At the Walker, as we studied Sterbak’s sculpture, I remarked that, after 25 years it looks more like beef jerky than the raw meat the artist’s wearing in the accompanying photograph. Still, my students’ discomfort with the sculpture was palpable. “What would it be like to wear it?” one of them muttered, shuddering, as she stood both rapt and repulsed by the archival image of Sterbak sitting on a gallery floor in her flesh garment: her expression betrays her discomfort, and her hands and the wood flooring around her are bloodied by the fresh meat.

“It might feel like your own body, only without any skin,” I replied, perhaps a bit too matter-of-factly. Admittedly, my own horror and fascination with the piece is tempered by my farm-girl roots and my evolution from meat eater to 30-years-long vegetarian to meat eater again, as much as my art critic’s sense of objectivity or postmodern love of irony. Alice consumed the “Drink me” potion and was ushered into Wonderland. Likewise, Sterbak’s dress unequivocally says “Eat me,” inviting a plunge into a different sort of rabbit hole. And, as my Dad later said, on seeing an image of Sterbak in her meat dress: “Well, she’s brought her own food to dinner!”

THE SYMBOLIC AND INHERENT VIOLENCE of Sterbak’s meat dress has been expertly parsed by scholars and critics. In her 1991 article, “The Flesh Dress — A Defence,” Sarah Milroy calls it a work of transgression and “female disobedience,” and an iconic metaphor for treating women as meat in a patriarchal society — hunted, purchasable, consumable (and those are the nice verbs). “The flesh dress is female, and it is made of meat,” Milroy writes, drawing attention to the dress as a gendered article of clothing for women, for its form — open beneath the hem, making the wearer more readily assailable — and in its material (from cattle, the female cow a term also derogatorily used as code for women), dressed through skinning, slicing, curing and packaging before consumption.

“In conjoining these two signs,” Milroy continues, referring to “dress” and “meat,” “Sterbak commits a major gender infraction, naming the equation between meat and women, both objects for male consumption, that patriarchal society would prefer to leave unspoken (and therefore more pervasive).” Here Milroy delves into Carol Adam’s 1990 book The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory, which grabs this interpretation by the jugular: “Sexual violence and meat-eating, which appear to be discrete forms of violence, find a point of intersection in the absent referent,” Adams writes. “Cultural images of sexual violence, and actual sexual violence, often rely on our knowledge of how animals are butchered and eaten.” Case in point: Hustler‘s famous 1978 cover image of a woman in a meat grinder; or, closer to home, dancer Zhauna Franks strung up like a side of beef during Ballet of the Dolls’ 2008 production of Rite of Spring.

As sculpture, Vanitas also sits comfortably within that well-known art historical tradition of the same name: vanitas (associated with 16th and 17th century Flanders and the Netherlands) or memento mori, still lifes representing vanity and decay, wealth and dissolution, life and death, that are created from withering flowers, dead insects, bones and skulls, and such symbols of time passing as candles and timepieces.

Gaga’s stunt has been parsed in its own right, in a BBC news magazine article among others. Some interpretations of the pop star’s iteration: it’s an anti-fashion statement; a feminist statement (although Gaga’s vapid explanation, “If we don’t stand up for our rights soon we’re going to have as much rights as the meat on our bones. And I am not a piece of meat,” does little to fortify this interpretation); a comment on vanity and aging (with a nod to Sterbak); an indictment of our hypocritical attitude toward eating meat (“The same people who are horrified by a raw-meat dress, may be wearing leather shoes which are themselves the product of dead flesh,” the BBC article states); and coming full circle, that Gaga’s version of the dress was just a meaningless stunt, donned purely for shock value.

“Meat dresses are strange,” one of my students later remarked in an email.

Dude, I thought, you have no idea.

Even assuming that last explanation is the likeliest, Gaga’s certainly not the first there either. Type “meat dress” or “flesh dress” into Google’s image search bar, and you’ll get everything from Gaga and Sterbak to meat chairs and meat shoes, to clothing made from meat-patterned fabric to models wearing shirts demarcating meat cuts to…. models. It’s a voyeuristic enterprise with little aesthetic value — Gaga, perhaps, in a nutshell. Her look-at-me celebrity irreverence in photographs stands in stark contrast to Sterbak’s muted suffering. Maybe that’s because Gaga’s dress is about her, while Sterbak’s Vanitas is about the dress. The latter goes beyond the singer’s Dada-esque gag through a familiar art historical act of re-contextualization, in that a live animal is transformed into a saleable product of the pasture, feedlot, slaughterhouse, butcher shop or grocery store, which is itself transformed into a work of art; it’s that Möbius strip of metaphor and meaning that produces in the viewer a sensation of the uncanny.

Freud called a symbol that elicits such sensations “the uncanny double,” as it functions as an unrepressed representation of what we fear most — our own mortality (there’s that memento mori tradition again). As Freud wrote in his essay, “The ‘Uncanny’,” that experience of the uncanny double occurs “when something that we have hitherto regarded as imaginary appears before us in reality, or when a symbol takes over the full functions of the thing it symbolizes.” When animal flesh, that slab of meat we throw on the grill with nary a thought to its provenance, is rendered and re-contextualized as a female (and feminist) work of art, it becomes a multivalent symbol, of our own violence against women and animals, of transient flesh, of life and death.

But isn’t meat also a form a sustenance? Isn’t it also reasonable to see it, not simply through the lens of violence, but as a a necessary transfer of one life to another to ensure health and vitality? And what about those instances where meat is a symbol of something else entirely, say, a family tradition, lifestyle, or personal totem?

“MEAT DRESSES ARE STRANGE,” one of my students later remarked in an email. Dude, I thought, you have no idea. Sterbak’s Vanitas, for me, is not only a thought-provoking museum piece, but also a remarkably trenchant comment on my own celebrated family tradition, underscored by a largely unspoken familial discourse. Two years ago, during a family reunion, I shocked — and delighted — my farm-grown parents, aunts, and uncles by announcing, “I want that,” as a platter of bison kebabs arrived at our restaurant table. In a single moment, I broke what had been a three-decades-long meat fast.

In my family, meat … no, make that steak symbolizes social power, financial largess, agricultural success, personal happiness, and family ties. It certainly means all that to my dad, at least, who each of us (particularly the women in the family) reveres. A farmer and cattleman who still raises livestock on his Wisconsin farm, Dad loves his meat and readily shares the bounty; he always brings a suitcase full of homegrown lamb and beef to family gatherings.

My decision to go vegetarian all those years ago was an extremely complex one. Suffice it to say, my dad took my choice personally. A while back, I decided I had to eat steak with him again. But at our large family dinners, where even my otherwise-vegetarian cousins partook of his homegrown lamb and encouraged me to do the same, I just wasn’t ready. When I ate red meat again it was, curiously enough, in South Dakota, the paternal homeland. And steak soon followed bison.

I grew up eating the bottle lambs we tended in our basement, without giving their impending sacrifice a single sentimental thought. By high school, however, I felt a glimmer of mourning for the prize-winning steer I’d wrangled in the ring at the county fair. My qualms only increased over time, and the choice to forgo meat altogether came soon after.

According to the plethora of recent tomes on eating local and organic, butchering one’s own meat is now considered trendy, evidence of “conscious” consumption, a more humane way to satisfy our carnivorous desires. My Dad isn’t making a statement; raising and butchering his own meat is just how he does things. Still, or perhaps because of this, my family is, shall we say, obsessed with meat. At least, we’re obsessed with the meat my Dad takes such tremendous pride in providing for us. We love him for it. We request it. We expect it.

And his take on Sterbak’s Vanitas? He wants the picture silkscreened onto an apron for Christmas. “Not Lady Gaga in her meat dress?” I asked.

“No,” he said emphatically. “She’s just doing it for a shock. It’s …”

“Skanky?”

“Yes, like her.”

Sterbak’s meat dress, he explained, is actually a dress, with shape and form, with intention. Perhaps, I venture, it’s even beautiful. I have a feeling that’s why Sterbak’s Vanitas: Flesh Dress for an Albino Anorectic has such particular potency for me. It seems to me a poem, of sorts, writ in muscle and blood, about women and animals, bodies and consumption, art and creativity, disobedience and reconciliation, family and sustenance. It is an uncanny double, in ever-mutating form, for that self-same piece of my story.

Related exhibition details: Midnight Party, the exhibition in which you’ll find Sterbak’s “meat dress,” will be on view at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis through February 2014.