Looking Back to Move Foward: The Rise and Fall of the Seward Neighborhood Graffiti Art Project

Writer Justin Schell offers a short history of the controversial public art experiment which invited artists to paint an "urban mural" on the old, recently demolished Riverside Market in the Seward neighborhood of Minneapolis.

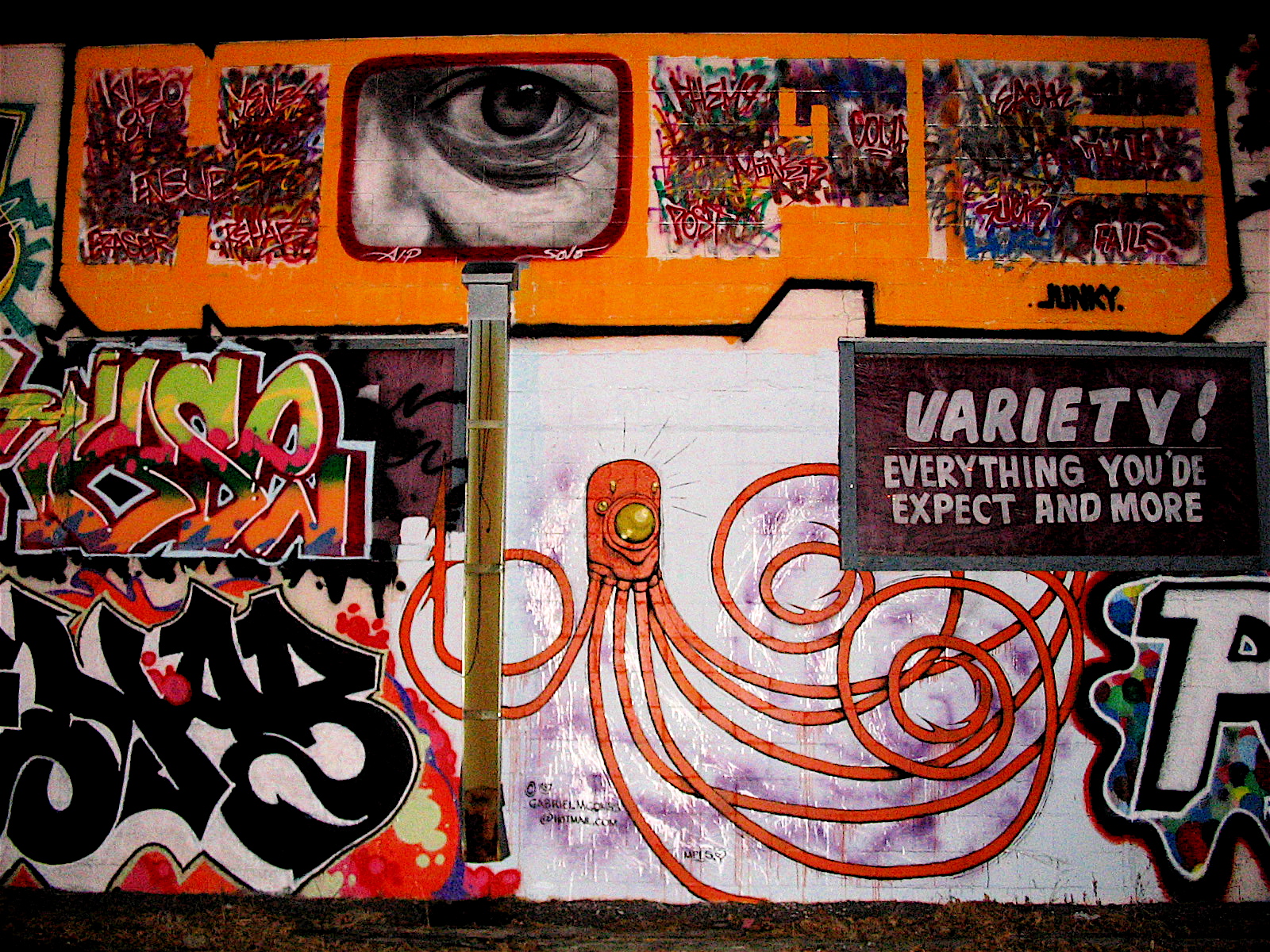

In the video for Brother Ali’s Take Me Home, a suited Ali and his DJ, BK-One, walk past brilliantly multi-colored graffiti. John Grider‘s Billygoat peers out from behind them while hues of kids skateboard, skip rope, and play basketball. This brief clip takes place in front of the old Riverside Market, soon to be replaced by the new Seward Co-op. The momentary harmony of the scene in Ali’s video–where business suits, neighborhood children and parents, and graffiti all co-exist peacefully–actually masks one of the more fraught chapters in the history of Twin Cities’ public art, as well as the history of Twin Cities graffiti, both in its quality and its consequences.

We can locate the Riverside Market within many different historical streams of Twin Cities graffiti. There are numerous spray art murals put up around the Cities, like the yearly repainting of Intermedia Arts in honor of its annual Hip-Hop summit B-Girl Be, projects organized by I Self Devine at Hope Community Inc, the work of Roger Cummings at Juxtaposition Arts, to name a few. Many of the most well-known MCs of the Twin Cities have roots in graffiti, including Atmosphere‘s Slug, who tagged the city under the name JEST. Last but not least, of course, are the legends of Twin Cities graffiti artfolks like CHEN, EWOK, CRISIS, CREST, LOGIC, and DENZ–who were members of such notable crews as AKB, TCM, and WND. But even memorable art sprayed on walls of fame like the Bomb Shelter near the White Castle on Lake Street, the graffiti beneath the 35W bridge, and the writers benches in Dinkytown have all gone the way of most graffiti, either destroyed or covered over by owners, the city, or other writers.

The idea for the Market project came from Seward Redesign, a non-profit community development corporation serving the Seward, Longfellow, Cooper, Howe, and Hiawatha neighborhoods in South Minneapolis. In the summer of 2006, Katya Pilling and other members of Seward Redesign began initial discussions with the Seward Neighborhood Group. Many Seward residents were tired of looking at the dilapidated Market and were especially upset at the large amount of illegal graffiti that dotted the building. With a purchase option on the building, these groups reached an agreement with the buildings owners to use the space for a public art project until the Seward Co-op, who was already in line to purchase the space for their expansion, began construction.

Intended initially to be a method of deterring graffiti, the project divided into two stages. First, there was a call inviting local artists to paint six panels on the front of the building. With donations from Valspar for the project, those artists (including teen writers like Jordan Hamilton, whose participation proved integral to the project) were given paint and other supplies for their work. The rest of the building, though, remained a magnet for illegal graffiti. With the approval of the citizen-based Riverside Market Task Force, and with the aid of a small contribution from the Seward Co-op, the entire building was opened to writers and artists.

Artists came to paint the Market on the weekend of November 11, which turned out to be the last good, sunny day in the fall of 2006. According to participating artist John Grider, word spread like wildfire that people would be out painting, and all day people drove in from all parts to paint. It was a first come, first served painting opportunity. The people that got there first typically ended up painting on the front wall, and people who showed up later painted on the alley side. Nobody got paid to paint, and everyone brought their own supplies. Organizer Katya Pilling remembers that there were thirty or forty people there; they had scaffolding set up, and it was very exciting. The turnout was just unbelievable.

The mixed community response to this project, though, illuminates the tension between illegal and legal graffiti; or, as some prefer to put it, between illegal graffiti and legal aerosol art. The spray can has accrued an intense stigma over the years and the Riverside Market project, both in the work on the walls and in the project’s ultimate end, is emblematic of the ambivalence accompanying this art form.

Though many in the neighborhood supported the wall, a number of others responded angrily and negatively to artists’ work, in spite of the legality of the project or the public discussions that went on before any scaffolding was put up. According to Pilling, chains of ranting emails from seething residents, accusations that participating artists were “felons,” “hoodlums,” and “hardened criminals,” and threats from the Park Board all came to Seward Redesign’s doorstep and inboxes. There was also a story on the WCCO evening news that, while maintaining a somewhat balanced view of both supporters and detractors, ended with the anchor’s incredulity and implicit skepticism about such a canvas.

While there were pointedly oppositional statements on the wall, including calls for impeachment and an end to “rape culture”, this didn’t seem to be the main concern of residents: their anger seemed to be aimed less at the content of the wall’s work than at the very practice of graffiti art on the wall. For some neighborhood opponents, it must have seemed that SNG and Seward Redesign weren’t inviting artwork for the wall, but rather that they were sanctioning the very kind of “blight” that the Project was supposed to discourage.

In response to these complaints, ASEK, one of the wall’s writers, pointedly told me that “allowing a legal, well-done graffiti mural to happen in a neighborhood does not invite more illegal graffiti into that neighborhood.” At the same time, though, Seward Redesign did pay to have a similar figure removed from the Matthews Park tennis courts when neighbors said they could match it to the work of someone involved with the Market project.

The Market wasn’t exactly a free wall, a space where anyone and everyone could paint whatever they wanted, though. Artists had to receive letters of permission from the SNG before they could work on the wall; these letters were intended to provide the artists with documentation which they could keep with them while they painted, as a way to ward off suspicious neighbors and, as it turned out, even more suspicious police.

Teen artist Jordan Hamilton, along with a number of his friends, was given permission by the project organizers to clean the wall by painting over destructive tags. Even though we had permission slips, he told me, neighbors were still calling the police. At one point we got stopped and the police didn’t even give us a chance to explain that we had permission. They just came into the alley and told us to get up against the wall. That type of stuff is messed up.

Given incidents like this and, more generally, a systematic intolerance of graffiti, legal or otherwise, in the Twin Cities (as well as nationally), Ward 2 City Councilman Cam Gordon’s take on the situation was especially nuanced and thoughtful. Soon after the paintings went up, Gordon wrote in his blog: “Public art, even if in a graffiti style, is not graffiti unless it is unauthorized. The City should not be an arbiter of aesthetics. Therefore, those who control the site may allow people–even people known as destructive taggers, if that’s their whim–to do public art without City intervention.”

Now that construction on the new Seward Co-op has begun, half of the old building is gone, reduced to brilliantly colored pieces of rubble, and the wrecking ball is surely not too far away for the rest. Yet from the beginning, everyone involved in the project knew it was only temporary.

“Graffiti, by nature, is not permanent,” Hamilton said, “and the fact that it’s torn down is not out of the ordinary. It had its time and it’s gone. Ironically, the fact that everyone involved in the project knew their work would be temporary likely gave the Market wall mural a longer life. “If we weren’t able to say this is temporary, that this is part of this development, it’s going to be down in a year,” Pilling said, “I probably would’ve had to go out there myself with a bucket of paint and paint over it because everybody was so angry.”

As for the future of the art still on the walls, Eric Hatting, the Project Manager for the Seward Co-op expansion, indicated by email that they plan to permanently reuse some of the art panels [from the front of the Market] in the new store. He went on to say that, while it is “impractical to reuse any of the aerosol work that exists on the Market building,” the Co-op is “planning for mosaics to be incorporated into the exterior plan and, as the design is refined, we plan to find spaces for other works as well, both inside and out.”

Looking ahead always means looking back, and for a number of the artists involved in the project, the Riverside market is no exception. John Grider said that “it was the first time in Twin Cities history where sixty or seventy graffiti artists all painted in the same place on the same day.”

Similarly, ASEK was impressed that so many writers from both Saint Paul and Minneapolis could work together on a project like this–it’s something that doesn’t happen all the time. In the end, Katya Pilling sees the project as a step toward greater dialogue about the place of this kind of public art, in Seward and beyond. “It’s [a public issue] and it would be great for people to have a dialogue about that and grow some understanding. I want to bring this conversation back.”

About the writer: Justin Schell is a freelance writer and grad student at the University of Minnesota’s Comparative Studies in Discourse and Society program. He’s working on a dissertation examining the diasporic and immigrant hip-hop of the Twin Cities.