Kitsch is Dead, Long Live Kitsch

Nathan Young looks into two new bodies of work, by Mathew Zefeldt and Andy Messerschmidt, through the historical lens of kitsch

The Minneapolis Institute of Arts’ MAEP Galleries’ current exhibitions feature work by Andy Messerschmidt and Mathew Zefeldt, two artists who have delivered kitsch sensibility from the historical cellar. The English word ‘kitsch’ migrated from the German, verkitschen, in the early twentieth century and was likely popularized in the 1940s by Clement Greenberg’s polemic on classist segregations of aesthetic taste. Originally meaning “to make cheap,” the German verb today can be translated as “to sentimentalize;” the related English word, “kitschy,” carries nearly the same meaning.

But kitsch these days has been complicated by the internet’s capacity for immediate global interconnectivity. In this context, kitsch describes so much more than simply high and low classes of art and merchandise. With our always-on networked computer interfacing and the pervasive influence of print and digital advertising, kitsch can refer to anything that interferes with the immediate relationship with our surroundings.

Recently, artist Sara Cwynar published a compilation of contemporary theories and images of kitsch, focusing on Roland Barthes, Jean Baudrillard, and Milan Kundera, who describes the term as “a folding screen set up to curtain off death.” Kundera, in particular, sees kitsch as a kind of denial in the form of moral or aesthetic inoffensiveness, like C.M. Coolidge’s poker-playing dogs, or perhaps the sentimental still-lifes used as part of Mathew Zefeldt’s exhibition, Repetition, Simulation, Repetition.

Zefeldt’s gallery room holds three different sets of handmade acrylic paintings, each relating to the others across the space. For the smallest of these sets, he copied four different 16-bit brick patterns from the backgrounds of Mario Brothers video games; he refers to these small paintings as “mirrors.” Zefeldt then reprinted high-resolution photographs of the same patterns onto vinyl sheets, which he used to completely cover walls facing their corresponding “mirror” paintings.

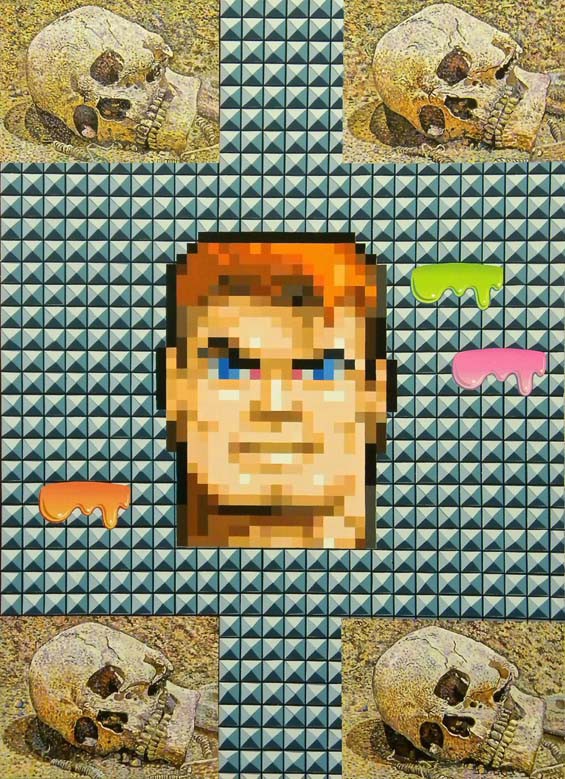

On canvases slightly larger than his “mirrors,” Zefeldt painted replicas of dungeon door graphics found in both Wolfenstein 3D and the Doom franchises. On canvases larger still, he has overlaid the same brick patterns from Mario Brothers with facsimiles of seventeenth-century still-lifes of skulls, ancient Greek sculptures from the MIA’s own collection, cartoonish globs of technicolor paint and, pulling again from Wolfenstein 3D and Doom, pixelated faces of the games’ avatars.

Zefeldt’s use of trompe l’oeil—here, simulations of already-artificial images—follows Baudrillard’s perspective on kitsch, which argues for a tension between reality as it is lived and reality as it is delivered to us through fictionalized representations and mass-media channels. This “kitsch reality” is akin to the highly processed but persuasive fictions of carefully orchestrated magazine photoshoots, the smooth masculinity of James Bond at the bar, and the romantic fantasies spun by Disney love stories. For Baudrillard, these mediations have become so deeply ingrained in the most banal aspects of life that even our day to day lived experiences take on the exaggerated qualities of “hyperreality,” a state of consciousness that cannot distinguish between real life and the simulated signs of reality.

But here, Zefeldt flips the alienation inherent in these arch-pop images by resuscitating their root content. His work succeeds as a memento mori, not through the overt use of bones and blood, but through a sobering engagement with mass media. Audiences don’t empathize with death through playing Doom. They might even shrug at the sheer weight of time represented by museum displays of ancient artifacts, or see still-life wreathed skulls with flowers as merely sentimental. But the range of styles in Zefeldt’s paintings—from graphic design and abstraction to rote-copies of figuration and photorealism—offer a rigorous counterbalance to the emotional vacancy that typically characterizes this form of kitsch. His recombinations effectively reinvigorate these time-worn tropes, reminding us of their original capacity to alleviate the pressure of mortality and history.

Next door in the MAEP galleries, visitors will find Andy Messerschmidt’s Delta Delta Delta Force. Messerschmidt’s art practice depends on a familiar system that generates yet another type of kitsch —the kind that adorns bookshelves, refrigerator doors, and lawns, depending on the season. A manufacturing business takes a culturally specific or sacred symbol from its own context and puts it into the marketplace; Messerschmidt then removes that kitsch commodity from the profit-cycle and returns it to a space of contemplation, the gallery, turning one type of kitsch into another.

When Walmart prints the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe on a casket, selling it with no mention of Juan Diego’s visitation, that icon becomes the type of kitsch that is stripped of complexity. On the other hand, to the skeptic who takes after Kundera, all formulations of religion are kitsch. By his reckoning, myths and allegories are the palatable fictions that mediate our lived experiences, stories we tell ourselves to reimagine the off-switch of death as eternal glory.

The title of Messerschmidt’s exhibition alludes to the type of wavelength emitted from human brains during sleep and also to the 126-year-old eponymous sorority whose insignia, designed by four Western American women studying at Boston University, muddles together symbols from ancient Egypt and Greece, along with astronomy and Eastern mysticism.

Sounds of delta waves mixed with people speaking emerge from a speaker on the gallery’s ceiling; red, orange, and pink stage lights fill the space. In the dead center of the room, Messerschmidt has placed a long, narrow shrine adorned by, but not limited to: green light-up zombie hands, nativity sheep, scepters tipped with maize and pumpkins, finial Christmas tree toppers, stuffed crows, plastic gold coins, and fake plants. Along the walls he’s painted large gold shapes inspired by the architecture of Mughal tombs, covered all over with shiny holiday wrap, disassembled streetlights, and Christmas tree skirts. Below one of these wall installations, a pair of white plastic vampire teeth sits atop a pile of Easter grass and fake snow.

Unlike the sorority’s insignia, ∆∆∆, the appropriation of which arguably abuses a culturally specific, perhaps even sacred iconography, Messerschmidt’s omnivorous freeplay depends on borrowing elements from his own cultural traditions. Born and raised in central Illinois, for example, he adopts materials representative of those used American manufacturing. Or, take the room’s centerpiece: he satirizes contemporary Western devotional practice by enshrining religious pluralism, laying bare the evidence of unabashed cultural appropriation particular to non-committal spirituality. And even though Messerschmidt has identified himself as a colonialist, by sentimentalizing and deifying mass-produced kitsch, he exploits a culture of white entrepreneurism.

All the same, Delta Delta Delta Force brings a sense of reverence to kitschy cultural objects. Without any irony, he personally remembers the source of each piece he uses, and regards them all with sentimental affection. “I truly believe,” he says, “that all these bits are glowing around us.” Much like Zefeldt, Messerschmidt’s practice recasts old images to impact an audience in novel ways.

The exhibitions at the MAEP help to update the definition of kitsch in ways that fairly represent both its perils and continuning benefits. As Cwynar would argue, the interference of kitsch on human experience is unavoidable. Before we’re affected by perfect, blockbuster bodies or promises of salvation, all of reality is mediated by the idiosyncracies of individual experience. With that in mind, it’s easier to appreciate how any point of view is likewise, itself, a variable dependent on kitsch.

Related exhibition information: Mathew Zefeldt’s Repetition, Simulation, Repetition and Andy Messerschmidt’s Delta Delta Delta Force are both on view at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts through December 28, 2014. Thursday, November 20, from 7 pm to 8:30 pm, MAEP coordinator, Chris Atkins, will lead a free, public artist talk with both Zefeldt and Messerschmidt in the galleries.