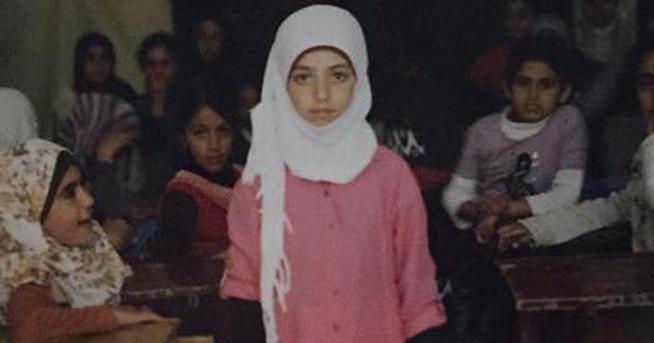

Humane Portraits from a War-Torn Region

Osama Esid's "Still/Life/Syria" invites a moment's reflection in the midst of Northern Spark's spectacle, to see people whose disrupted lives seem far from our day-to-day in all their humanity and dignity.

This piece originally appeared on Twin Cities Daily Planet and is reproduced here with permission.

When Twin Cities-based artist Osama Esid first arrived at the Adana camp in Turkey to take photos of Syrian refugees, he was told he’d have a mere 45 minutes inside. He says he begged for more time to be able to meet the residents, gain their trust and hopefully take some photos. He recalls how, once inside the camp, a Mr. Souleyman invited him to dinner. Before the meal was served, Esid asked to take a photo of Souleyman’s empty tent – not the people, not the food, just the tent. He explained his project, saying he wanted to be able to take that tent outside the camp, to photograph others inside it anywhere in the world. “Mr. Souleyman loved the idea,” Esid remembers. “He said, ‘Somehow you make me feel like my great-grandfather’s house is still open for all the guests’.”

And so began Osama’s incredible project, Still/Life/Syria. Out of the hundreds of photos he took inside the camp over the course of several days, 12 five-by-six-foot prints will be on display at Mill Ruins Park this Saturday night during Northern Spark. The work is presented and commissioned by Mizna, an Arab arts organization based here in Saint Paul. And, yes, the Souleyman tent will also be on-site; a limited number of visitors will be invited to stand in front of it to get their picture taken. Esid will show the photos of Northern Spark “guests” in the Souleyman tent to residents at the camp in September, when he returns to Turkey.

Photos and news footage of people displaced by Syria’s civil war flatten our experience of the conflicts there. We, the viewers, can always close our browsers, flip the page, or turn the channel without really acknowledging the people at the center of that violence; it’s all too easy to feel removed from the reality of their lives. And that reality is grim. There are an estimated four million Syrians who have been displaced by conflicts in the region thus far. Thirty-six thousand people are living in the very refugee camp where Esid spent a week taking photos. But there is resilience and hope in their stories, too.

“When we talk about the situation, we need to understand that it is not permanent. So, let’s take a souvenir shot of this little, borrowed time,” says Esid, as he describes his interactions with residents of the camp.

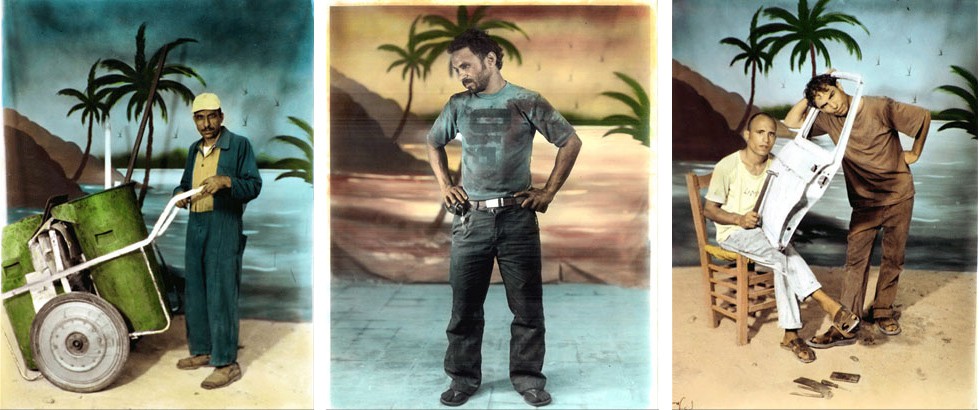

Lana Barkawi, Mizna’s executive and artistic director happened upon Esid’s work by chance. In the process of moving from their former home in NE Minneapolis to Saint Paul, she found a book he’d left behind some time before; inside were a note and phone number. She called him, and thus began their relationship. Mizna eventually published a book of photos from his Cairo laborer series in 2013.

“I love his work, and I love that he builds relationships with his subjects,” says Barkawi. “It’s not the camera of a journalist who is very removed from the situation.” She says what drew her to Esid’s work was that evident empathy for his subjects. When you meet Osama, she says, that connection feels real and immediate. He is warm, chatty, and quick to talk about his subjects. He speaks of the people in his photos as if they are family, his close friends. And for the Still/Life/Syria project, they are, in fact, kindred. Esid left Syria when he was 22. In a sense, he is as displaced from his home as those he photographed in the Adana refugee camp.

“I can’t imagine him working any other way…take the style of his work in a place where people are at a crossroads –they don’t know what the future holds…. He’s someone who shares a background with them, as a Syrian and an artist. He brings that empathy to his work,” says Barkawi.

For Still/Life/Syria, Osama worked with Type 55 black-and-white polaroid film, which yields both a positive print and a negative. He gave the positive prints to his subjects, who were ecstatic about getting something so immediate, so tactile from the experience. (He says, many of his subjects asked if they could look at the back of his camera; they were expecting a digital image.) Esid then took the negatives and made prints from them, many of which he then hand-colored – a technique that harkens back to early Middle-Eastern photos of the late 1800s. Such attention to traditional craftsmanship is part of Esid’s whole esthetic; his penchant for using hand-made cameras and analog equipment yields stunning results.

Stepping into his studio for our interview, I think of 1920s photo salons and studios. Amid prints, rolls of film, large printers and various lights are 100-year-old cameras, positioned atop wheels and which print on silver gelatin.

For Esid, this project is not about getting people to donate to the Red Cross or calling your senator.

“There’s nothing needed from this work. There’s no policy that needs to be made from this,” Osama explains. “We just need acknowledgement.”

For Northern Spark-goers, the night-long festival is often about spending the night soaking up the first blush of summer with fun-filled art projects, exploring the city with fresh eyes. Still/Life/Syria invites something a bit more than that: a pause for quiet reflection in the middle of all the fun and a moment to muster our moral agency and really see these people, whose disrupted lives seem so far from our day-to-day, in all their humanity and dignity.

Related links and information:

Find Twin Cities Daily Planet’s recommendations for more things to see and do at the 2015 Northern Spark.