Flow, Response, Disruption: On Dance and Finance

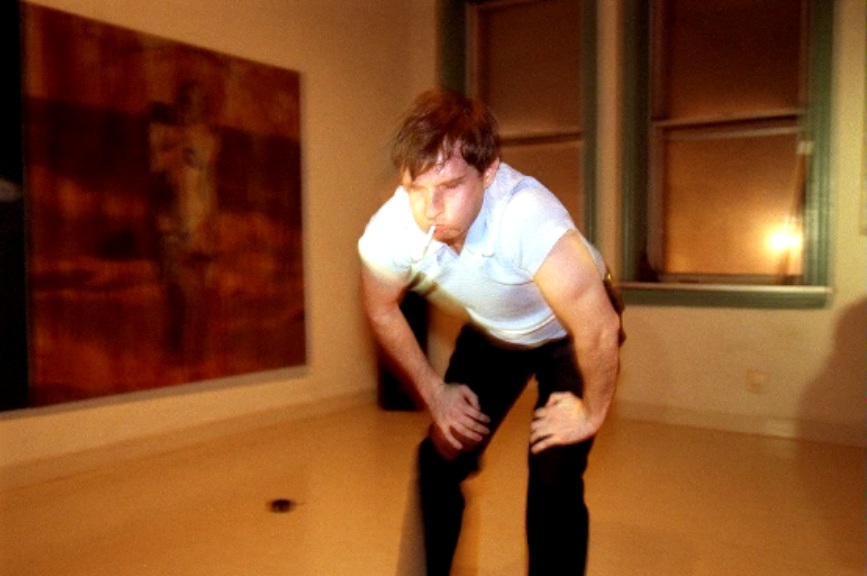

Colin Rusch, a former mnartists.org staffer and Minneapolis-based choreographer, demonstrates how the artist skills of listening, sensing, and predicting outcomes transferred directly into his second career as a Wall Street analyst.

For most people, making out with a jelly donut and appearing on CNBC to discuss the prospects of disruptive technology companies like Tesla have little in common. However, as my career unfolded, the two seemingly disparate activities have proven deeply akin. I’m unusual as a Wall Street analyst, given that I made dances (which integrated select donut videos on occasion) until I was 30, before starting as an assistant at an investment bank. The career change was prompted by a desire to understand capital flow, to be more effective in pursuing social and cultural change. And while that intention has been realized in various capacities, I’ve also learned there is a deeper connectedness of artistic and business process.

Fifteen years later, since moving to New York and entering the finance industry, I lead a research practice focused on sustainability and disruption in the transportation, power, materials, and agriculture sectors. At root, the skills I learned working in dance are the same as those I now use every day as an equity research analyst for an investment bank where my role is to share my opinion with investors on whether particular stocks will trade higher or lower. Core to both dance and equity research processes is an ongoing cycle of witnessing, reflecting, assessing, and acting, with the purpose of coalescing a (hopefully) poignant moment for a clearly defined audience. With continuous intention setting, improvisation, and adjustments along the way, the comparison is straightforward.

Articulating the process

Witnessing. The act of showing up has been validated in both my artistic and finance pursuits. In the performance world, there is an ongoing calendar of seeing peers’ work, both in the rehearsal studio and in its final form, as well as tracking the critical discourse in the field. Similarly, in my role as an analyst, there is the morning routine of checking company, industry, and world news, along with a steady calendar of industry conferences and company meetings. In both worlds, being both present and attentive is essential to remaining current and relevant.

Reflecting. Digesting those experiences and information after gathering them can be a bit obtuse, but is crucial to insightful action. There is a process of taking notes, sitting with an experience, and engaging the imagination on how the elements might fit together, based in part on past experience. I find that reflecting is also a generative activity, in the sense of imagining everything that could come from the initial experience. Without this portion of the process, there is only reactive thought and action—which, while important in certain contexts, is fundamentally limited.

Assessing. After some digestion comes deliberate, critical engagement with the experience and information. In the performance world, it involves revisiting notes, reading reviews, discussion with collaborators and peers, and testing ideas in rehearsal. In my role as an analyst, I revisit notes from past meetings, discuss with peers, test ideas via data-driven analysis, and debate ideas and theses among my team. In both contexts, the assessment phase bleeds into a planning effort towards which, if any, actions are appropriate.

Acting. This final stage in the process is the public presentation of the work. In the dance world, this is typically a performance. In my case it also involved curating and presenting other artists’ work, facilitating collaborative community events, and writing for a monthly magazine. In my current role, I publish industry and company analysis, speak with investors, present at industry conferences or to companies’ boards of directors, and engage with the media, such as TV interviews like this.

|

|

Dance/Performance |

Equity Research |

|

Witnessing |

Attending shows or rehearsal, watching within my rehearsal, moving through the world in an attentive way. |

Discussions with management teams/industry contacts, site visits, attending conferences, moving through the world in an attentive way. |

|

Reflecting |

Taking notes, sitting with an experience, engaging the imagination on how elements might fit together. |

Taking notes, sitting with an experience, engaging the imagination on how elements might fit together. |

|

Assessing |

Revisiting notes, discussion with peers, testing ideas in rehearsal. |

Revisiting notes, discussion with peers, testing ideas via data-driven analysis. |

|

Acting |

Creating/presenting performance, facilitating series like Mulch, working as a catalyst in the arts community via platforms like mnartists.org, and working with the McKnight Foundation on events like convening the local dance community. |

Picking stocks effectively, publishing industry research, visiting clients, organizing client events, and media appearances. |

Why is it important?

While the parallels between the processes are direct, I’ve found that putting this knowledge into practice in the finance world has been uniquely informed by my dance and somatic training. That training has proven my biggest asset as an analyst. To the best of my ability, I try to engage at each step with a nuanced somatic attentiveness that includes all five senses, as well as my imagination and memory.

The late Pauline Oliveros developed a practice called Deep Listening, which she has described as “a way of listening in every possible way to everything possible, to hear no matter what you are doing.” It includes all of a person’s sensory experience as well as their imagination, memory, and dreams. While my dance training was based in ballet, modern dance, Klein Technique™, Feldenkrais, Body-Mind Centering®, yoga, tai chi and other somatic techniques, ideas like Ms. Oliveros’ permeated the artistic community I grew up in. I would describe my background as Deep Listening-oriented.

As I transitioned into the world of finance, this Deep Listening orientation has proven invaluable. Embedded in the practice is an implicit empathy and wonder when experiencing any entity, whether it is a company, a piece of information, an intellectual property portfolio, an individual portfolio manager, or a dance rehearsal, the sound of birds in the morning, or the smells of the morning subway commute. It is a practice of being sensitive.

Beyond that sensitivity, I believe it is characterized by an underlying curiosity. What is that? What has it come from? And what could it become? I am fortunate to lead a team of four analysts who have weathered years of my insistence that if we ask better questions, we get better answers. Often simple questions are the most effective. Those three questions—“What is that? What has it come from? And what could it become?”—have proven powerful for me in both the art world and in finance.

From the outside, the finance industry is often seen as ego-driven, crude, and selfish. All of those things can be true. But it is also shaped by subtle attention to detail, the patience of waiting for the right moment, a broad understanding that the market will always be larger than any individual or balance sheet, and that everyone is engaged in a dynamic, interdependent, and reflexive process. And I have had the good fortunate to train for that world in the generous, brave, wise, and persistent Minneapolis dance community.

That is why I think the connection of these processes is important. As a global community, we face increasingly complex and pressing challenges driven by intensifying social, economic, and cultural interdependence. And from my perspective, the practices of sensitive listening, curiosity, and thoughtful, direct action nurtured in the arts community not only produce important art, but seem to be at the heart of hopeful, respectful, and sustainable paths forward addressing those global concerns.

This article is part of the series by guest editor Kristin Van Loon.