Conversations on Improvisation: Douglas R. Ewart

Pamela Espeland continues her series on improvising musicians with Douglas R. Ewart, a multi-talented and award-winning musician, composer, instrument builder, lecturer, educator, and visual artist who splits his time between Minneapolis and Chicago.

DOUGLAS R. EWART IS A MAN OF MANY GIFTS AND ACCOMPLISHMENTS: improviser, composer, performer, visual artist, sculptor, mask maker, instrument builder, teacher, lecturer, arts organization consultant, founder and leader of numerous musical groups, past chair of the important and influential Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), winner of Bush Fellowships, McKnight Awards, a US/Japan Creative Arts Fellowship, and Jerome Foundation grants. And then some.

According to his bio on the AACM website, Ewart’s talents have expressed themselves in so many forms “that the whole might be mistaken for the work of a small culture rather than one man.”

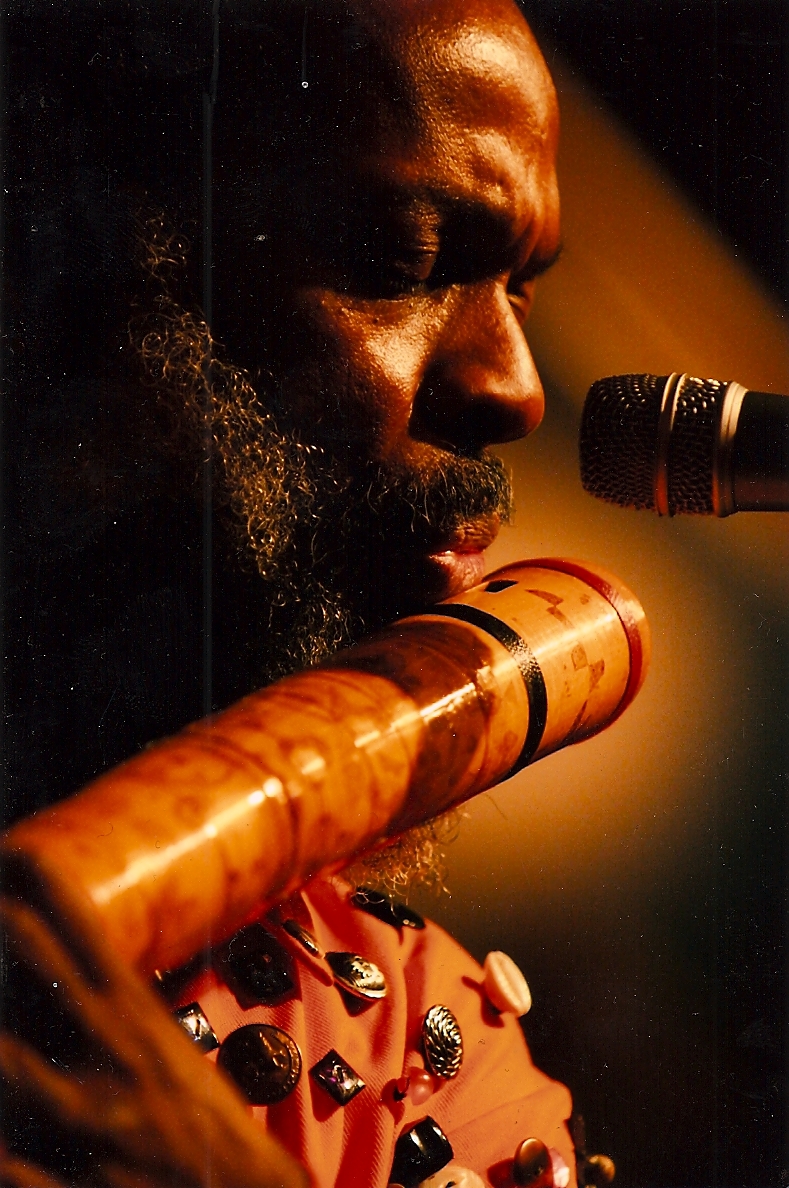

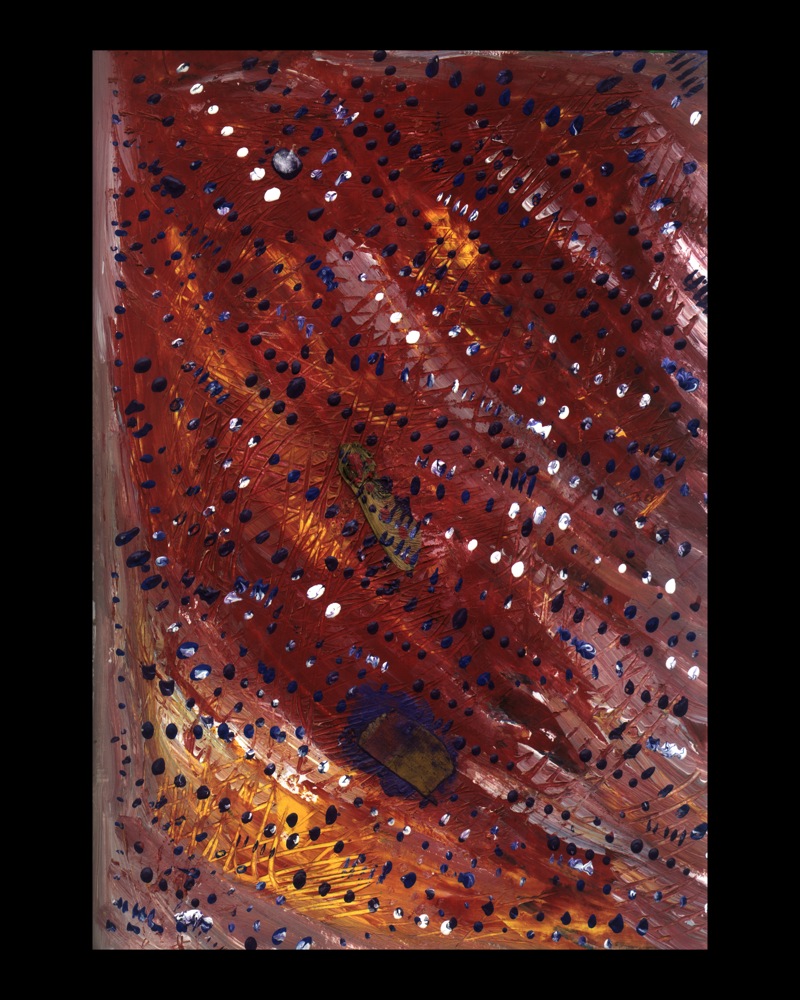

A performance by Douglas R. Ewart is an invitation to the unexpected. I’ve seen him play fairly straight-ahead saxophone, a glass didjeridu, and a crutch equipped with a hamster wheel. He makes even the fiercely inventive Cecil Taylor look lazy. Taylor comes out, plays the piano, and recites a poem or two; Ewart performs music of his own making on instruments of his own devising, wearing clothes he has designed and embellished with original art. From the colorful hat on his head to the bells on his ankles, he’s improvisation in human form.

Born in Kingston, Jamaica, Ewart came to the United States at age 17 and studied to be a tailor at vocational schools. Luck had brought him to Chicago, where the AACM, then in its infancy, was teaching young inner-city musicians for free. His teachers included Muhal Richard Abrams, Roscoe Mitchell, and Joseph Jarman, all now icons of avant-garde jazz; in 2010, Abrams was named an NEA Jazz Master. Ewart learned from them that music is a life-and-death matter. He takes it seriously, but with a generous laugh and a philosophy he calls “Embraceable You”: Every day is an embraceable day.

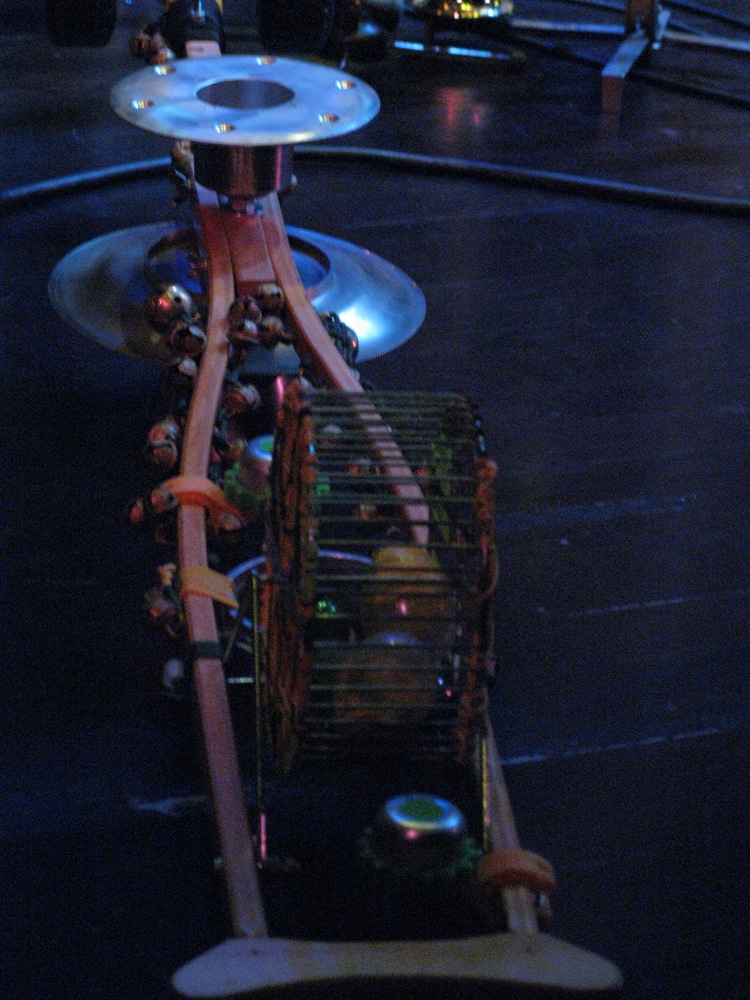

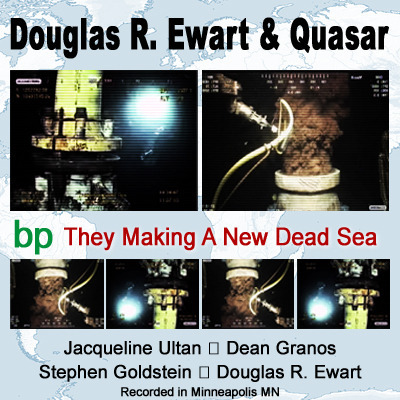

Currently, Ewart divides his time between Minneapolis and Chicago, where he has taught at the Art Institute of Chicago since 1990. He plays dozens of instruments and has released several recordings on his own label, Aarawak. He leads a wide variety of musical ensembles including Douglas R. Ewart and Inventions, Clarinet Choir, Nyahbingi Drum Choir, Quasar, and the newly formed Stringnets for stringed instruments and clarinets. His large-scale collective project, Crepescule, has been performed in Chicago, Minneapolis, and Paris. Ewart Sonic Tops premiered in Chicago last year, and he’s hoping to bring it to Minneapolis. His latest idea involves racquetballs and tennis balls.

That he had time for a lengthy interview last month was something of a miracle.

______________________________________________________

Pamela Espeland: You’re leaving for Chicago again soon?

Douglas R. Ewart: I’m getting ready to do some composition workshops there: one on the music of Latin America and the Caribbean, the other on a graphic concept of composing. It’s as stringent as traditional notation, but people who can’t read lines and spaces can read it. So, it’s very good for young students, and at the same time it shows them that you can’t just do anything with music — there’s a discipline to it. I’ll show them some compositions I’ve done, and we’ll develop a lexicon.

PLE: For example?

DRE: Well, maybe French fries means five notes played below C, or lemonade means high notes played like quarter notes. You can develop this whole thing that’s possible to interpret fairly quickly, but which still has directives.

PLE: When did you first become interested in improvisation?

DRE: We made toys [during his childhood in Jamaica], and a lot of times we didn’t have every resource you needed to make whatever it is you were making. So we’d go out and scout around and find pieces of wood. We’d take old bent nails and straighten them. If you build things, you have to improvise, because it never goes as planned, especially if you don’t have unlimited resources.

PLE: Did you make instruments as a child?

DRE: Mainly toys. We made our own scooters, tops, kites, bows and arrows, and catapult guns. Another thing we did was play marbles. You have to improvise a lot with marbles, and you have to compromise. When you play games, you run into things you have to solve and resolve if you’re going to continue without conflict.

PLE: Was there a moment when you realized that musicians improvise, and more specifically that this was something you could do?

DRE: I was exposed to improvising musicians as a young man; that’s one of the things that prompted me to play. I heard [ska trombonist and composer] Donald Drummond, [trumpeter] John Moore, [trumpeter] Raymond Harper, and so on. I saw [drummer] Count Ossie live when I was, maybe, 11. It was a mesmerizing experience. He was my first inspiration to play. I could simulate playing him by using tin cans, so that was the first instrument I made: hand drums from tin cans. I would try different ones. On some, the edges were too sharp; on others, the metal was too stiff. I would look for cans that were suitable.

PLE: Who were your other early influences?

DRE: I had a cousin who had an enormous collection of records, and I used to listen to music at his house and read all the liner notes. So, I was exposed to people like Clifford Brown, Charles Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, and [John] Coltrane as a child. I wanted to play the trumpet. At the time, I had no idea what instruments cost; it just seemed prohibitive, so I never asked my folks for one. It didn’t occur to me that maybe I could have gotten an instrument from the US, or that someone could have bought one from a pawn shop for me.

PLE: What instruments do you play?

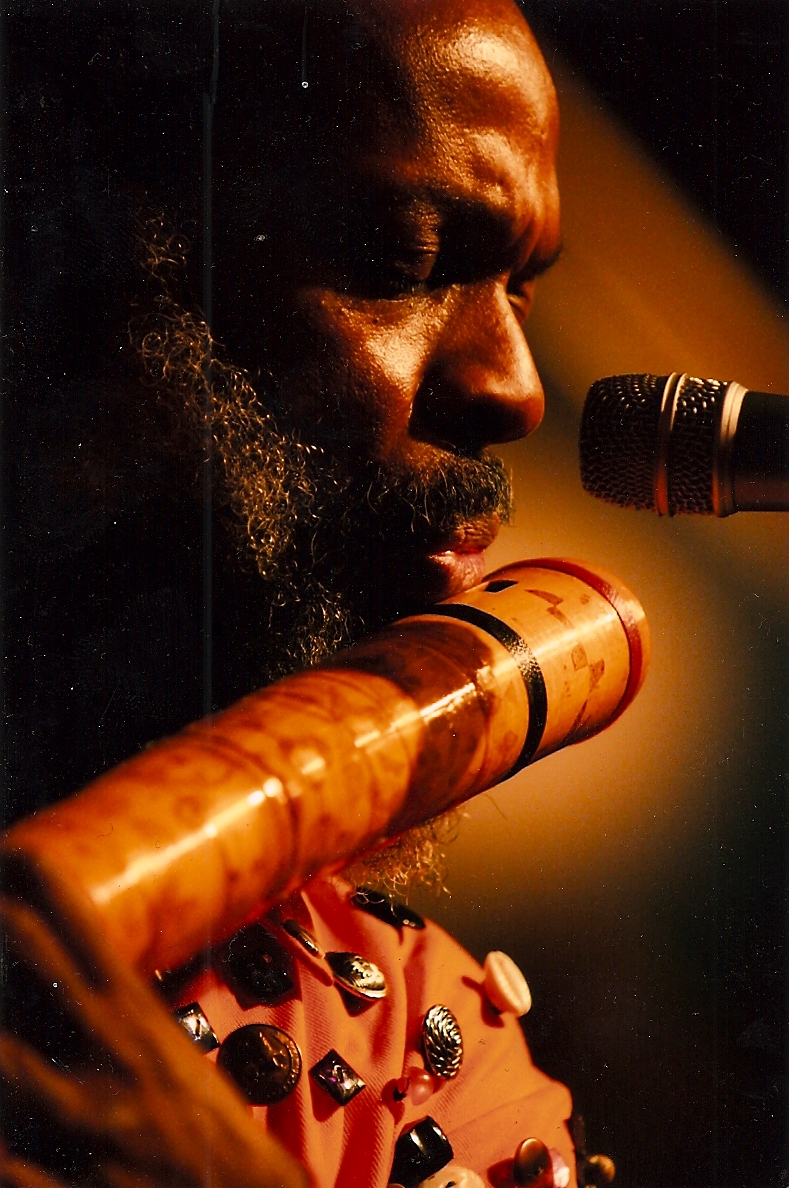

DRE: Alto saxophone, sopranino, soprano, and tenor. Bass clarinet, and the clarinet family — E-flat, B-flat, alto, contrabass. Flute, piccolo — all sorts of flutes; shakuhachi, panpipes, ney. [He pulls out a carved flute he made in 1979 and plays a few notes.] Didjeridu. I’m really interested in the didjeridu for a lot of reasons: the sound, and the way that people of all ages and backgrounds are affected by it. It has a powerful, very appealing presence. I noticed that when I began taking it to schools. Even the noisiest room would get quiet to try to figure out what was going on.

PLE: Tell me about your glass didjeridu.

DRE: I went to Michael Boyd at Foci Glass [in Minneapolis] to see if he would make me a glass didjeridu; I had already made several others from plastic, metal, bamboo, and eucalyptus. We talked about it, and when I was about to leave his shop, he said, “I have some glass tubes upstairs. You should come and look at them.” They were hanging and you could see the light refracting through them; that was their purpose, to provide a light show. He allowed me to try one and it was perfect. He said, “You can have it. I’ve been waiting for the right person to come along and you’re it.” He has since given me a half-dozen. There’s one that’s very translucent and golden yellow. The sound is incredible.

PLE: You also play percussion instruments and bells.

DRE: I have hundreds of bells, a whole collection of bells. I have many different racks with various percussion instruments hanging from them — gongs, cymbals.

PLE: And then there are the instruments you invent. What are the names of those that have names?

DRE: The Ewartophone, kind of a cross between a tenor saxophone and a bass clarinet. The Bamboon, fashioned after the bassoon; I also play the bassoon. And I build drums. I think particularly about items people discard, like tennis rackets and racquetball rackets. They’re very durable, and they make perfect frame drums. I take ball bearings from old discarded bicycles and put them between layers of skin, and you have a rattle, almost like a snare.

PLE: You also make rainsticks.

DRE: And all kinds of instruments out of skis and crutches.

PLE: Some of what you do might be perceived as sheer spectacle.

DRE: There’s nothing wrong with a spectacle if it’s also more than a spectacle. One of the things I think about when I do my work is magic. Magic is spectacle.

PLE: What do you mean by magic?

DRE: You want people to listen. You want people to be involved. You want people to be curious, inspired, provoked. You want people to have a visceral experience. I do. That’s one of the reasons I wear different clothing when I perform. Think of shamans — they were the first performers in human society. They had different regalia, drums, rattles, whistles, flutes, which they used to make the rain, ask for the sun, and get the baby well.

PLE: How do you define improvisation?

DRE: To me, improvisation means thinking. People tend to think of improvisation as something you do on the fly. That’s true to an extent, but when you improvise on an instrument you have to understand the mechanics, the technical capabilities, and the demands of the instrument in order to play freely. It’s like improvising a poem. You don’t just jump up and do that. You first learn aaah baah maah — that takes years. You develop a vocabulary. Then you learn how to put phrases together, and sentences. Then you have to have delivery, and nuances; you can’t just be monotonal. It’s a layered skill. Then you have improvising by yourself, improvising with other people, and improvising with the audience. Part of a great performance is give-and-take between the performer and the audience. Sometimes that’s a cultural thing; you go to some places and people don’t react.

PLE: Many of your projects bring the whole community into the experience, something not normally done in an improvisational setting.

DRE: In my performances, whether formal or not, there’s always room for adding people. If one of my good friends comes in with an instrument, I say, “Hey, I would like you to play.” That’s another form of improvisation.

PLE: What about the Sonic Tops project?

DRE: I made tops for some of the children who live on my street, from spools. Those are some of the easiest to manipulate and fabricate. The children were so taken with them that I thought — this is interesting, how kids of all ages (and adults as well) are fascinated by tops. The kinds of interaction tops elicit are profound. Adults often play with kids from their level, standing up. With tops, adults have got to get down on the ground; you’re at eye level, more or less, and an exchange occurs, because some people don’t know how to spin a top, some people do know, some people just learned, and then there are different ways to spin. These variables help to create a theater of learning. “Wow, how did you get your top to do that?” “Come here and let me show you.” I started thinking — this is the perfect thing to get people to talk to each other, to get a whole family to gather together, to get older people to do something they haven’t done in 40 or 50 years.

So, I made tops from spools; then I made some from bamboo, which is hollow, and I began to see the possibility for sound. I started collecting all sorts of things to make tops — ash trays, candlestick holders, plates, cups, bowls, saucers, old 45s and 78s, LPs. Part of the concept is to show young people they can be more inventive, more resourceful, and not rely so much on buying stuff they can make for themselves or repair.

For the Sonic Tops project, I wanted to make 50 tops and have maybe 20 people spinning them. Then, I wanted more than just spinning tops. So, I added Double Dutch [jump rope], tai chi, Capoeira dance, a poet on roller skates and a poet walking around, musicians — all with videographers filming and projecting what was going on, live.

[The Sonic Tops project was first performed in Chicago in 2009. See photos and a video clip here.]

PLE: So, it’s safe to say that Douglas Ewart is not a man who has put aside childish things.

DRE: Oh, no! I embrace childish things. I always want to maintain a childish curiosity, a childish fervor. Having been a teacher for many years, I know how brilliant children are. I have been astounded by their accuracy and acumen. I also think children are a good barometer of what kind of person you are. When they give you the pass, you’ve gotten the pass. When I play for an audience of children and I really get to them, it’s far more gratifying to me than when I play for adults. I do really abstract stuff and children love it.

PLE: What goes on in your head when you’re improvising?

DRE: A lot — you’re constantly making choices. You’re eliminating things, as opposed to always adding things. It’s sort of like being at a banquet. If you mix up too many foods, it will be a horrible experience. So, choice is an important part of playing for me — and planning. You come with skills, and how you apply them will vary depending on circumstances. It might be a warm day and your instrument might not be very responsive, or it might be really cold and your pads might stick. All kinds of things might happen.

PLE: While you’re improvising, as you play, are you thinking about what you’re going to do next, what you’ve just done, or what other people around you are doing?

DRE: All of it. You think about what you’ve done, and sometimes you don’t like what you’ve done.

PLE: And then?

DRE: One chastises oneself, but you can’t stay in that zone, because if you do you’re going to mess up even further. Being ready to forgive yourself and others is a crucial part of any interplay. It’s sort of like falling down. You can either lie there and grunt and inhale dirt, or you can get up, dust yourself off, and proceed.

PLE: What happens to your sense of time? Does it speed up or slow down?

DRE: It depends on the experience. Sometimes it can be agonizing, and you think, “Boy, I’ll be glad when this is over!”

PLE: How do you know when it’s working?

DRE: You don’t always know. Sometimes you feel, “Oh, this is awful!” and you listen later to your tape and think, “That stuff wasn’t too bad.” Sometimes you think, “This isn’t clicking” or “This is too rudimentary.” So you lay out and let the other person have it, or you take charge and furrow right through. Sometimes you can coast into something, or you can let something drift. It’s about flexibility. There are different kinds of improvisation you don’t want to be involved in when you get older. Like mimicking.

PLE: Isn’t that call-and-response?

DRE: I don’t know if it’s call-and-response. There are a lot of ways I can call you. The whole call-and-response thing is a cliché. People talk about it like there’s only one kind of music, African-American music, that has call-and-response. But almost every culture has it. The Chinese have call-and-response. The Japanese. Irish. Italian. If you say eeh-dah, I can say ooh. I don’t have to answer eeh-dah. I can whistle.

PLE: What else besides mimicking don’t you want to do?

DRE: I don’t want to be like, “This is the Miles Davis group in 1957 with Coltrane in it.” There are bands like that. I go and I listen — I support any kind of sound endeavor — but I don’t want to be involved in playing that. You do a certain amount of that when you’re learning your craft, but as you get older, hopefully, you have something to say and it’s not in that vernacular.

PE: You want to be original.

DRE: Absolutely. I’m an explorer. I like trying different things. I like to be unpredictable to myself. That doesn’t mean not being grounded or steady, not working on the instrument, or not dealing with any of the traditions you may be able to pull from. But I don’t see anything that can’t be a part of what I’m doing musically.

PLE: If I had never heard you play, what could I do to prepare for the experience?

DRE: Don’t. There is no preparation. The only preparation is to be open to listen. It’s like going on any jaunt. [He invents a dialogue.]

Let’s go walking in the morning.

“What’s going to happen?”

What do you mean, what’s going to happen?

“What are we going to do?”

We’re going to walk. But since you brought that up, let’s go to Como. There’s an arboretum-

“What’s an arboretum?”

It’s a place with a lot of trees. Right now, the apple blossoms are magnificent.

“What else?”

Look. Let’s just go out there and get among the trees and then we’ll see what happens.

______________________________________________________

Douglas R. Ewart and Quasar were featured recently on TPT’s weekly arts broadcast, Minnesota Original.

______________________________________________________

Related performances:

Ewart and the Nyahbingi Drum Choir will perform on the Jackson Stage in Grant Park during the 32nd Annual Chicago Jazz Festival on Saturday, September 4, at 12:00 pm.

A performance at the Cultural Wellness Center at 1527 East Lake Street in Minneapolis is in the planning stages. We’ll update as information becomes available.

______________________________________________________

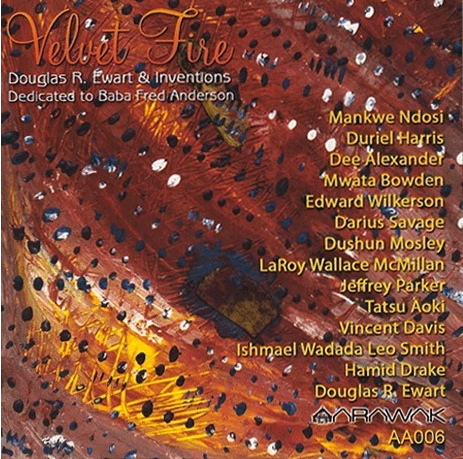

Discography:

Douglas R. Ewart and Inventions, Velvet Fire (Aarawak, 2009). Recorded live at the Velvet Lounge in Chicago and the Guelph Jazz Festival; dedicated to Baba Fred Anderson.

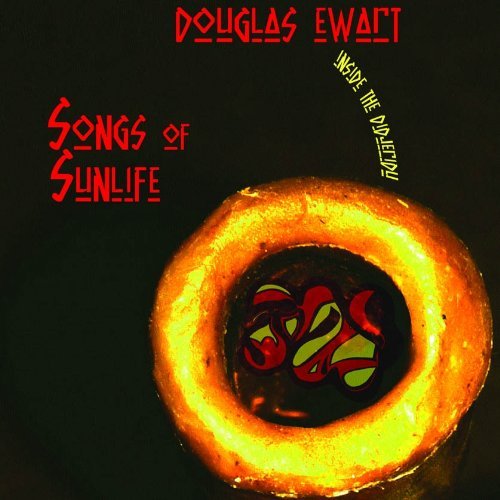

Douglas R. Ewart, Songs of Sunlife: Inside the Didgeridu (Innova, 2003)

Douglas R. Ewart et al., Vision Fest: Vision Live (Thirsty Ear, 2003). Includes “Crepuscule IV in Powderhorn Park.”

Douglas R. Ewart and Inventions Clarinet Choir, New Beings

Douglas R. Ewart and Inventions Clarinet Choir, Angles of Entrance (Aarawak, 1998)

Douglas R. Ewart, Bamboo Meditations at Banff (Aarawak, 1994)

Douglas R. Ewart & Inventions, Bamboo Forest (Aarawak)

Douglas R. Ewart & Inventions/Clarinet Choir, Red Hills (Aarawak)

Ewart has also recorded with Muhal Richard Abrams, Anthony Braxton, Chico Freeman, George Lewis, Roscoe Mitchell, Henry Threadgill, and others.

______________________________________________________

Suggested reading:

“The multi-faceted Douglas Ewart” — An interview by Willard Jenkins.

A Power Stronger Than Itself: The AACM and American Experimental Music by George E. Lewis (University of Chicago Press, 2008). Ewart figures prominently in this essential history of the AACM, winner of the 2009 American Book Award.

______________________________________________________

About the author: Pamela Espeland writes about jazz for MinnPost.com, blogs about jazz at Bebopified, and keeps a Twin Cities live jazz calendar.