A Voice for the Unsung: Kao Kalia Yang

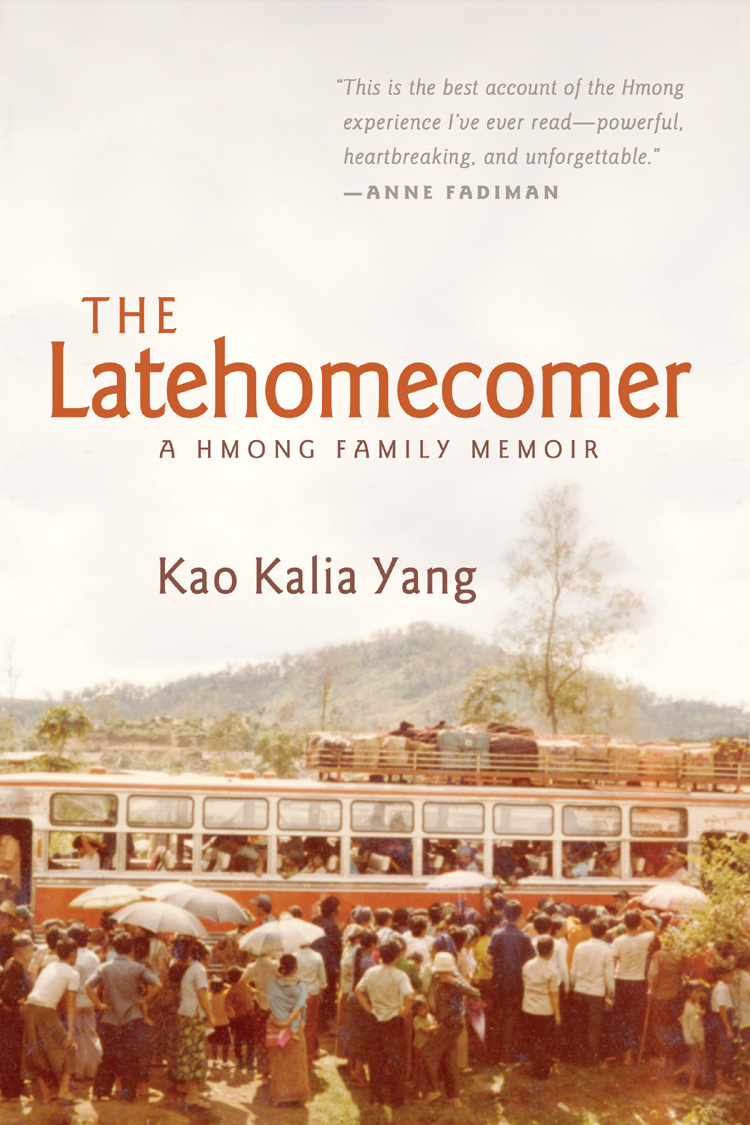

Author Kao Kalia Yang talks with writer Shannon Gibney about her new memoir, "The Latehomecomer," which traces her own family's flight from their native home after the Vietnam War.

FROM THE DAY THAT SHE WAS BORN, SHE WAS TAUGHT THAT SHE WAS HMONG by the adults around her. As a baby learning to talk, her mother and father often asked, What are you? and the right answer was always, I am Hmong. It wasnt a name or a gender, it was a people. When she noticed that they lived in a place that felt like it had an invisible fence made of men with guns who spoke Thai and dressed in the colors of old, rotting leaves, she learned that Hmong meant contained. The first time she looked into the mirror and noticed her brown eyes, her dark hair, and the tinted yellow of her skin, she saw Hmong looking at her. Hmong that could fit in all of Asia, Hmong that was only skin deep.

So begins Kao Kalia Yang’s The Latehomecomer: A Hmong Family Memoir (Coffee House Press, 2008), among the first books written by a Hmong author to be published by either an established commercial or literary American press. Yang calls the memoir, a love letter to my grandmother, who passed away in February 2003. At the beginning, all I was doing was trying to write down all of these things that I never wanted to forget about her, says Yang. Because her biggest fear was that she would be forgotten one day, I wanted to tell her that I wouldnt forget her. I also wanted to let her know that if I wasnt going to forget her, then other people wouldnt either.

Spanning all the outposts in her familys journey from the jungles of Laos to the Ban Vinai Refugee Camp in Thailand to their eventual settlement in St. PaulYang’s tale communicates insights gleaned from these experiences that seem far beyond the vision of her 27 years. Her spare, careful prose belies the lush bounty of emotionality that runs through her account and which immediately connects the reader to her story.

In the section, The American Years, she writes, I have an image of my mother and father on a bridge over a highway. The sky is a rumbling gray, perhaps in anticipation of the fall rain. They are little more than two outlines, standing together, not touching, facing the same direction, standing still. In their thin jackets, the sizes all wrong, too big and too long, they watch people with work to do and places to go, young children buckled safely in back seats. That first year, and for many years after, my parents spent a lot of time yearning to be strangers. I felt it then, and I feel it now. It is hardly ever enough to simply be alive.

This is the kind of ethos, this kind of pathos, that constitutes The Latehomecomers dense and engrossing atmosphere. Such is the effect, according to Yang, of experiencing history not as an individual, but as a family, and ultimately, as a people. I was born into this story already, observes Yang. Yesterday, somebody asked me, How long did it take to write the book? And I said, Four years to do the writing. He said, And 22 years to do the living, right? And I said, No. Centuries and centuries to do the living.

Yang adds that her singular purpose and passion for these stories gave her an advantage over some of the very talented writers she studied with in the MFA program at Columbia University. They were writing about drugs, or about other things that I knew were part of the contemporary American landscape. But I never got the feeling that they were really quite convinced that that was their story to tell yet,” she reflects. “But in my heart, I was already burning with a story.”

Translating her family’s saga into book form, however, wasnt initially on Yangs agenda. It became a book,” she explains, “because the more I wrote, the more I saw how it could happen. And because the Hmong are new to written language. It wasnt until the 1950s that a Hmong written language was taught and used. Its a new medium for us. To say that we’re going to go into this thing thats literature, and that it will last longer than the newspaper, or the TV its kind of incredible. Especially for me,” she says, “because I love books. I read books over and over again. For me, theyre always alive.

This isnt to say that the process was easy, though. There were lots of defeats, remembers Yang. One day, I was reading on the Vietnam War and noticed that the Hmong werent anywhere [in the account]. Just like the American history books I read all through college and all through high school “Hmong” wasnt mentioned anywhere. And yet, I knew that war was responsible for us being here, and that it killed two-thirds of the people I belong to. People are still dying in the jungles of Laos, remnants of this fight. In the process of writing this book, I learned that that wars dont end.” She pauses then says, “There were so many lessons. What happened to old men and women during and after the war? I looked for the answer to this question everywhere, but no one answered it satisfactorily. So, I faced the problem: how could I begin to tackle this question, especially as it concerned my grandmother, who was already old by the time this war had come?

How do refugees become refugees? she asks. We dont really become such a thing until somebody writes us off as ‘refugees,’ until we believe we are ‘refugees.'” “There’s a moment, intellectually, when you know you are Hmong,” Yang says, “when you feel you are. So, these were all of these questions that I asked, myself. When I couldn’t find the kinds of answers I was looking for, that’s what prompted me into writing, to try and answer them for myself,” she explains. “But before you can tackle them for yourself,” she goes on, “you have to know that your questions have been addressed elsewhere or in different waysyou’re not necessarily the first to think about them. I think every writer tackles these issues, just in different ways.

Yang continues to feel compelled to do this difficult, yet vital work whether it is by helping refugees with writing and translation through her company Words Wanted, or by producing The Place Where We Were Born, a video on the Hmong experience in the Ban Vinai Refugee Camp. Through it all, Yang remains grateful for the deep engagement Minnesotans and others around the world are having with The Latehomecomer. She says, I know that my readers are intelligent, at the end of the day. A lot of them have lived a lot longer than I have, and they understand the human story. So, if I talk about these things, and I do it well enough, then the work is done for me.

To find out more about Kao Kalia Yang, or to find out where she is reading next, visit www.kaokaliayang.com.

About the writer: Shannon Gibney is a writer who lives in Minneapolis.

About the author: Born in 1980, Kao Kalia Yang is the co-founder of Words Wanted, an agency dedicated to helping immigrants with writing, translating, and business services. A graduate of Carleton College and Columbia University, Yang has recently released The Place Where We Were Born, a film documenting the experiences of Hmong American refugees.