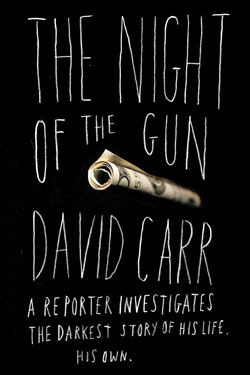

A Reporter Investigates the Darkest Story of His Life – His Own

Beloved MN expat and NYT media critic, David Carr, died February 12, 2015. This quote from a 2008 interview for Mn Artists feels both poignant and apt: "I now inhabit a life I don't deserve, but we all walk this earth feeling we are frauds. The trick is to be grateful and hope the caper doesn't end any time soon."

Editor’s note: David Carr died suddenly February 12, 2015. We’ll sorely miss reading him.

It started way before he lost his job at a Twin Cities business magazine, before he wheeled through dozens of downtown and south side bars, or cooked up back door deals with sketchy characters. It began even before he snorted, smoked, and shot up those countless lines of cocaine. It was long before that one morning when he woke up hungover in an Uptown apartment, caked in his own blood (just one in a succession of such hungover, regretful mornings). Way before he tried to break into his best friends apartment, and long prior to the time that same best friend ever threatened him with a gun or called the cops, David Carr‘s struggle with addiction began. Dependence on cocaine and alcohol arrived early and hard, but it was the part about the gun that Carr had always struggled to understand. Even with all the madness surrounding the times when his addiction ran hot, how could that have ever happened? What would possibly make his best friend threaten him that way?

So, when David Carr, now a columnist for the New York Times, decided to write a memoir about his addiction and recovery, he wanted to tell a true story. His commitment to grounding the book in hard evidence didn’t stem only from a desire to avoid the kind of negative publicity that has ruined the careers of other writers; Carr was also driven by his own need to know, to investigate these gaps in time his mind couldnt fill. He started by tracking down the facts behind the events of the “night of the gun.”

Carrs memories told him that he was a nice guy who partied too much, lost his job, had a few problems with the law, got his life together, survived cancer, and worked really hard to make up for his old mistakes. His memories left him confident that he was someone who, even in the worst of times, would never have owned a gun, much less have trained it on someone. It’s normal to expect that, as someone whose mind had been made foggy by alcohol and drugs, Carr’s personal recollections from that period might play tricks on him from time to time. But as Carr investigated the story of his life through the eyes of others around him, particularly when he looked into the “night of the gun,” he discovered that his remembrances were more than foggy, they were backward. Contrary to what he’d always believed, the evidence seemed to put a .38 Special in his possession, and his friends’ recollections put him – not his friend, as he’d always thought – behind the gun that night. Stunned by that revelation, Carr decided once and for all that his own memory was suspect, an unreliable witness to the events of his life. And it’s from there that his investigations into the truth behind his story proceed.

_________________________________________________

I’d always thought writing a memoir was a really stupid idea

it was clichéd, a way of commodifying the addiction.

_________________________________________________

The Night of the Gun isn’t like other memoirs. Carr says, “I’d always thought writing a memoir was a really stupid idea- it was clichéd, a way of commodifying the addiction. There are a lot of recovery memoirs out there and they all seem to tell the same story.” So, when he set out to commit his personal history to book form, having decided his own recollections were unreliable, he used his twenty-plus years of experience as a journalist, seeking out uncompromised sources of information and public record, to flesh out the details. He conducted three years of investigative research into his own past and, in the process, discovered a number of incidents he had completely forgotten about (and would have preferred never to remember).

For example, in Night of the Gun, Carr recalls some unremembered, risky “games” he’d played while on road trip to a friend’s wedding:

(Ralph) finally tired of the game and pulled up with the window open. I got the jump on him, pulled him through the window, and before he knew what happened, he was face-down in the flower bed in front of the country club. Donald and I got in the Town Car and drove away. Back at the hotel . . . there was a knock at the door. There was Ralph, chest heaving, dirt still on his tux, wielding a butter knife of all things. . . By the time hotel security got there, Ralph was working me over, and I was upside down against an adjoining hotel room door. I did not fare well. My hand was fractured, my head was lolling to port, and I had a limp.

And here’s a similarly “lost” incident from a relationship with a woman he adored:

It is immediately clear from Doolie’s recollection that there were times when I hunted her down. ”You hit me, and somehow you pushed me down. Do you mind if I do this?” she asked, as she put her hands on my shoulders. “It might be kind of pathetic, but you had me on each shoulder, and you were hitting me back and forth and were saying, ‘I’m going to kill you'”.. . . Every word of it was true. I had done these things.

Carr found records of arrests and Hennepin County court documents. He ruefully unearthed recollections of providing crack (and innumerable black eyes and broken ribs) to the mother of his twin daughters — born two-and-a-half months prematurely because their mother, Anna, got high while she was pregnant.

_________________________________________________

’You had me on each shoulder, and you were hitting me back and forth and were saying,

I’m going to kill you.’ Every word of it was true. I had done these things.

_________________________________________________

He writes:

I did not so much move in with Anna as suddenly become someone who did not leave. . . I treated her as an ATM, using her drugs and money almost at will, while she seemed more than willing to make the trade. In spite of the fact that I was the one who stepped up and raised our children, who shook off the Life, there are times when the moral high ground rests with her. I hit her, for one thing. For another, whatever she did, she did out of a kind of love. My presence in her life was far more mercenary.

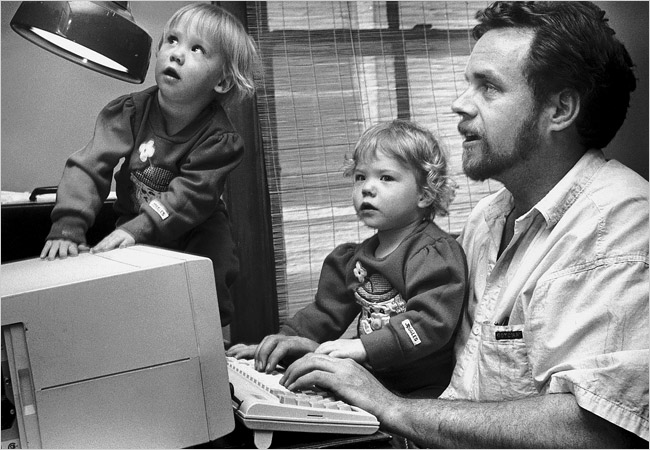

It took five trips through rehab (though Carr only remembered four of them) over a number of years for him to end the madness and violence and to win back custody of his twin daughters. It was then that he started working again as a journalist, this time for the Twin Cities Reader.

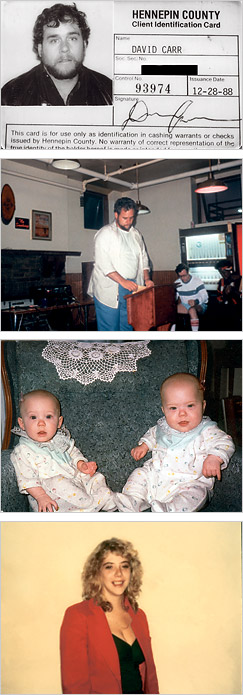

Photos from David Carr’s past: mugshot and family photos appear courtesy of the author, drawn from the New York Times website

A reader needs a strong constitution to make it through the grimmest parts of Carr’s addiction narrative. He could have made his account more palatable if he’d hung the harder details on a scaffold of tongue-in-cheek banter, with jokes about sweat and bad hair, or quips comparing the violent, seamy parts of his life to any number of embarrassing action movies from the ’80s. But Carr does not protect the reader (or himself) from the story’s sharp angles this way. That said, he freely admits that, often during the interviews about the book, he still feels removed from his story, almost like he’s talking about someone else’s life. And the account resulting from his investigations is unflinching and often stark: he’s got lots of eyewitness testimony attesting to the fact that the bad parts of his life were, indeed, really bad.

Carr’s story pivots around the births of Erin and Megan, his twin daughters born to Anna, their crack-addicted mother, and stranded in foster care, and for whom David fights righteously to win custody.

_________________________________________________

David Carr isn’t interested in being anyone’s hero, and he’s not invested in

rendering his painful past into a colorful-but-ultimately-feel-good read.

_________________________________________________

Carr renders these wrenching struggles matter-of-factly and without pathos, and that emotional breathing room allows the reader to persevere, to stay with him as he makes the long climb back to health. There lies the power of his telling: David Carr isn’t interested in being anyone’s hero, and he’s not invested in rendering his painful past into a colorful-but-ultimately-feel-good read. Instead, as you read his narrative, Carr is utterly candid, approachable and fearlessly earnest. And he’s not asking for sympathy, either: “I was born in a really nice suburb. I went to a good school and had a really nice family. I had every opportunity and a million second chances. I lived when a lot of my good friends died. I have a really good job now and a family that I like. How bad should you feel for that guy?”

Photo courtesy of David Carr

Night of the Gun defies facile categories: this isn’t an easy redemption story that takes you through addiction to epiphany and then, finally, to redemption, lessons learned, and recovery. Carr’s struggles in the second half of his memoir, post-cocaine, are as unrelenting as those in the first: he banishes coke from his daily life, only to find himself battling Hodgkin’s lymphoma. He wages a custody battle with the twins’ mother and learns, over time, how to navigate the waters of single parenthood. He works his way through the ranks as a journalist and is eventually hired at the New York Times. And then, after 13 years of sobriety, he writes that he set out to become a nice suburban alcoholic and succeeded.

Carr is frank: ”Barring a necessary and opposing force, the obsession that lives in an addict is always in the basement, doing push-ups, waiting for an opening. And all the treasure, human and otherwise, will not change that math. That’s why reading all the junkie memoirs that ridicule various programs of recovery makes me laugh.” What are they offering as an alternative, he asks: “Free will? Moderation? A flash of self-realization followed by a lifetime of self-control?”

A 2005 DUI put him back in detox and into the recovery meetings he now attends regularly. As of now, he’s become a responsible guy: he continues to write for the New York Times as a new media columnist and culture reporter, and he has a suburban New Jersey life many would envy. The way Carr’s memoir unfolds, his story elicits compassion without pandering; he’s not asking for kudos for coming out the other side of his addictions. Instead, he presents a harder, truer accounting of himself as an ordinary, deeply flawed individual who persevered and, just as importantly, who’s gotten lucky.

”You are always told to recover for yourself, but the only way I got my head out of my own ass was to remember that there were other asses to consider,” he shrugs. “I now inhabit a life I don’t deserve, but we all walk this earth feeling we are frauds. The trick is to be grateful and hope the caper doesnt end any time soon.”

It’s likely impossible to understand exactly what it is that makes an addict or alcoholic pursue one more drink, but Carr’s story clarifies one unvarnished truth about substance abuse: the destructive fallout of addiction is inescapable and widespread. Carr never woke up in the morning with the intention of destroying his health and career, or with the aim of alienating the people he loved; but, under the sway of his addictions, he undeniably caused a great deal of damage. And what makes Night of the Gun unique among addiction memoirs is that the author has documented, videotaped, recorded, and published a detailed personal history of his damage to others with a startling degree of respect and clarity. One other clear and solid truth rings out from every gritty page: even in the midst of a devastating addiction, redemption is always there, but only if you’re willing to look it squarely in the eye and work for it.

Michèle Campbell writes on literature, wellness, and spirituality.