A Monument of One’s Own

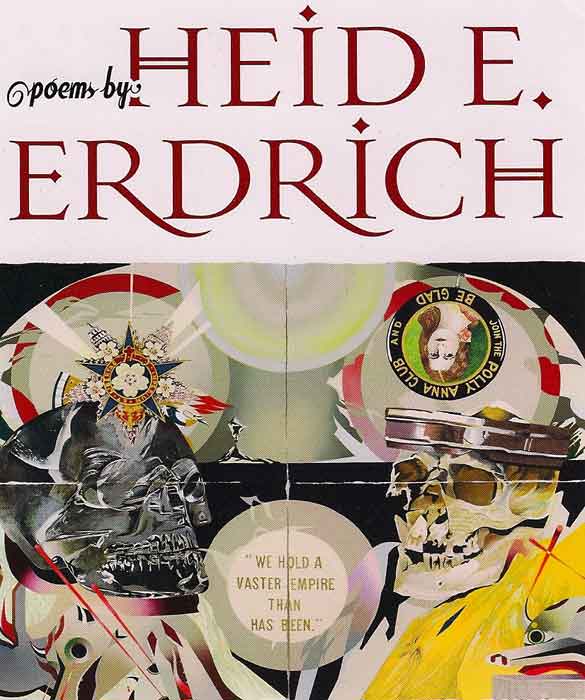

Writer Britt Aamodt sits down with 2009 MN Book Award winner, poet Heid Erdrich, to talk about her acclaimed collection, NATIONAL MONUMENTS.

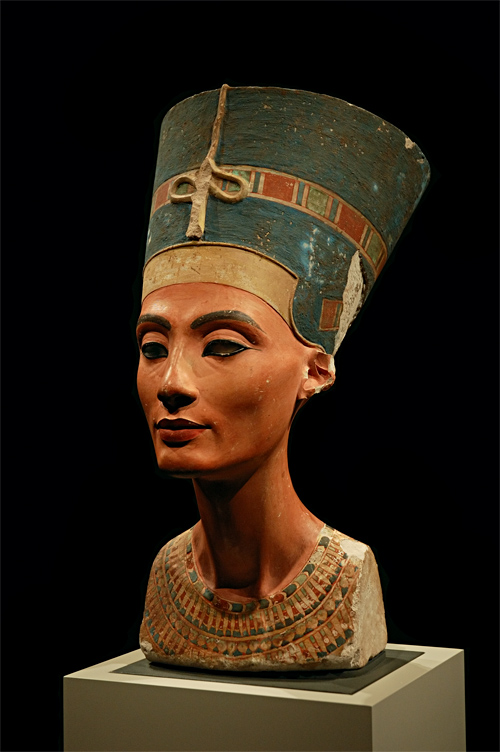

IN NATIONAL MONUMENTS, POET HEID E. ERDRICH documents the strange case of Nefertiti, an ancient Egyptian queen acclaimed as the “most beautiful woman in the world” after Ludwig Borchardt’s 1912 excavation of her ravishing likeness, in the form of a sculpted head, from the sands of Tel-el-Amarna.

I know what historians say: Nefertiti vanished until

the bust found — found me radiant eternally.

The pedestal spot brought the Sun upon me again.

Again He spoke my true name: The Beauty Arrived.

Wife of Egyptian pharaoh Akhenaten and stepmother to Tutankhamun (a.k.a. King Tut), Nefertiti bore many titles in her day: Mistress of Sweetness, Mistress of Upper and Lower Egypt, Exuding Happiness, Beloved One. But withered crone?

“A recent museum study discovered that Nefertiti [as represented by the sculpture] had lines and wrinkles. I thought, how dare they? How dare they revise her beauty and qualify it by her middle-agedness,” relates Erdrich.

“It cracked me up. So I read more about Nefertiti and found out that she and her husband were sun worshippers-literally. They worshipped the sun god Aten. Of course, sun worshippers are going to have wrinkles.”

Taking on the mantle of the faded beauty, the poet glories in “Nefertiti’s Close Up”:

So the Sun touched me, drew my lips

to His and kissed until I flamed.

How hot His tongue, like the flick of a lizard.

So what if I bear His marks, His flecks and lines?

“The Nefertiti poem was one of the first to come out of my RSS feed,” says Erdrich, whose morning email jolt of the arcane, outlandish, incredible, historic and scientific news provided a good chunk of the inspiration and research behind National Monuments.

National Monuments, published by Michigan State University Press, is Erdrich’s third book of poetry, and her fourth (including Sister Nations, a book she anthologized) to snag a coveted Minnesota Book Award nomination. Not that she’s counting. Erdrich deals in words, not numbers, and she plays those words into imaginative leaps that travel across time-from the 9,300-year-old bones of Kennewick Man and the French Revolution to a modern-day War on Terror detainee — and place, over the Black Hills and into Grand Portage, cyberspace, myth, literature, a lover’s arms, and academia.

Her poetry is research-laden, a fact which might sound snooze alarms in other hands. But with Erdrich’s sense for comic turns of phrase, a poem riffing on the bureaucratese of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) comes out sounding anything but stodgy: “If an object calls for its mother,/ boil water and immediately swaddle it“, “Avoid using bones as drumsticks/ or paperweights, no matter/ the actions of previous Directors or Vice/ Directors of your institution“, “Never, at anytime, sing Dem Bones.”

“I started out wanting to write a book based on my response to national literature, American literature. My response to Indians in it,” says the poet, a member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Ojibway and a former professor of literature at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul.

Erdrich gave up tenure in 2007 to pursue her writing and to devote more time to the Native community. A co-founder of the Turtle Mountain Writing Workshop and Birchbark House, a bookstore specializing in indigenous-language literature, she is also curator at Ancient Traders Gallery in Minneapolis.

The transformation in Erdrich’s professional life in 2007 roughly corresponded to a fresh re-visioning of the book she was writing. “Someone had said, ‘There are no national monument markers in places that are sacred to Native people,'” Erdrich recalls. “So, I thought I was going to write about that. I examined those sacred places, took trips. But what came to me were ideas about the body: the body as monument, the body as nation-building site.”

And then there were those tantalizing news stories that came in through her RSS feed. How could she resist incorporating the true story of pharaoh Ramses II’s stolen hair turning up on eBay, or the 12,000 indigenous skeletons housed in drawers beneath a university swimming pool, or Amazonian tribal blood sold to online buyers?

Erdrich divides the poems in National Monuments into these three phases: Grave Markers, American Ghosts and Discovery-An RSS Feed Series. Grave Markers takes up Erdrich’s interest in national monuments and explores the notion of the body as monument.

American Ghosts comprises the poems Erdrich crafted as a counterpoint to representations of the Indian in American literature. This section includes the poet’s response to William Carlos Williams’s “To Elsie” poem. Where Williams spoke about his Elsie (calling her “the half-breed”), Erdrich serves as her psychic host, allowing Elsie to reincarnate for one day to sit in on a class studying her poem.

She endures the comments about her body,

“the great ungainly hips and flopping breasts.”

What if her ample chest had been her pride?…

What if she thought, Ah, at last

A poem about someone I know.

“My poems are a conversation,” says Erdrich. “I think it’s the choice of a poem to be able to continue conversations others might have had. I often speak [in my poems] about thoughts and feelings that are really not mine.” It’s a writing habit that leaves some of Erdrich’s editors and close readers feeling cheated. “They complain, ‘There’s nothing personal in there,'” she laughs. “The voice I use isn’t mine. It can cut through and join conversations and speak with many voices. I like to think it’s a wiser voice, one with certainties I don’t have.”

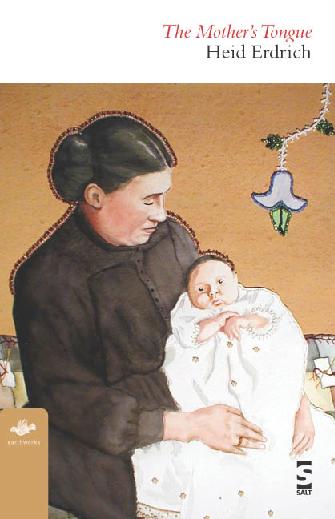

On April 25, National Monuments was named the 2009 Minnesota Book Award-winner for poetry. Erdrich’s two previous books of poetry are the Minnesota Voices Award winner Fishing for Myth (New Rivers Press, 1997) and The Mother’s Tongue (Salt Publishing, 2005).

About the author: Britt Aamodt is a Minnesota writer living in Elk River. She has received artist grants for her creative fiction, and currently writes and produces radio plays with the group Deadbeats On the Air.

Read below for a poem, “Some Elsie,” from National Monuments

(Michigan State University Press, 2008)

Some Elsie

And there she sits, Elsie, in American Lit.,

at the Community College or Harvard or the U.

The sleek New York TA reads how her family

“married with a dash of Indian Blood”

and thus escaped the fate of the “pure products”

Wm. Carlos Wms. saw go crazy.Does she sit, terrified or transfixed?

Waiting for someone to turn, look at her and think,

There she is, that Elsie.

So what if she was hemmed all around with murder?

Or if a few of her relatives had screws loose?

She’d deny bathing in filth from Friday to Sunday.

What a girl does on the weekend,

come on now, that’s her own affair.She endures the comments about her body,

“the great ungainly hips and flopping breasts”

What if her ample chest had been her pride?

What if, at first, she flushed at the sound of

“voluptuous water” and took it as a compliment?What if, at first she thought, Ah, at last

a poem about someone I know.

Imagining that she’d strain after deer, too,

if stuck in the suburbs passing pills.

But now, even knowing her hips,

somehow become, the TA says, a text,

doesn’t help the sting when she thinks

there’s some truth she’d like to express,

broken brain or not.

Reprinted with permission from the publisher and author