Shape Is a Promise: On YOU SAY YOU LOVE ME AND I COMMIT TO FRICTION

Orienting an exhibition to embrace friction, build connectivity in reciprocity, and see shape as a question

YOU SAY YOU LOVE ME AND I COMMIT TO FRICTION is a group exhibition on view at Public Functionary until September 28th, curated by Sati Varghese Mac featuring the work of BakiBakiBaki, Delaney Keshena, Ifrah Mansour, Nailah Taman, Nat Kim, and Cameron Patricia Downey. The following is a collection of reflections from the curator, interwoven with responses from the artists.

Love is never a complete statement; at the core, it is more of a pleading than an invitation. Yet, it is impossible to hollow our love. Even an accidental slip of the words can plead for something else, the utterance a confrontation grounded in the possible. The title of this exhibition extracts a line and a half from June Jordan’s “Intifada Incantation,” an insistent and haunting poem charting the expanse of Jordan’s love–a love that necessitates its own politic.

NAT KIM

“These ingredients like love, commitment–together, they sound a lot like we’re avoiding friction, we’re going to really meld and harmonize, and then you throw friction in there and it suddenly makes everything churn.I’m excited to think about how we create shapes that change us. There is certainly some room to say that archive does change a person and by journaling and creating self awareness that shapes how you and yourself interact. But it’s also interesting to create shapes that have some kind of mysterious effect on ourselves and others.

That’s where the general post-Enlightenment-era fear about magic and witchcraft comes from. It wants to deny what’s possible and you don’t have to believe in the whole metaphysical aspect necessarily, but you can use intention and object creation together.”

Trusting disorientation, displacement, discomfort, distance, even disenchantment, I orient this exhibition to the resting potential within the intimacy of a compassionate scrutiny, especially when it is not elegant. Showing up inside out can untangle our commitments. Returning to this intimacy as a discipline can produce consistency–an antidote to repetition. Through the wandering hand, the artists link their craft to an obvious continuation, a promise to the unknown.

DELANEY KESHENA

“In coming home, the form of metal is deeply related to the story of my great-uncle coming back from boarding school. I’m almost placing that relative of my family into the metal. Thinking about the spikes almost as a family member. Any idea of relations that come from my understanding of Menomini language, or my understanding of cultural practice, are really quite queer, in indescribable terms, it’s so different from the norm.There’s queerness in that the greatest, safest relationships that I feel in my life are with my friends and people who I’m not so blood-related to. And I think there’s a way that in my practice I’m also kind of doing that with material, asking it to be safe and be a stand-in for story or relationship that is in my own life.”

Sati: So you’re building your relatives?

“Yeah, kind of. I think so… I’m asking for safety in a material and using–for example–dirt, which is something so sacred. There’s this one story I was told, about when someone was scared and lost, they remembered they were told by their grandmother that if they ever get into a situation like that, to grab a little bit of dirt and essentially, you put it in your mouth like you do with chew. In a way, the earth being a grandmother to everyone, you’re just asking your grandmother to come with you and give you a little bit of protection.”

Sati: Have you ever done that?

“No, but I might now… There’s a lot of memory inside of dirt. All the things that make the dirt and once lived are in the dirt, but I also like to think that when we walk on top of it, or when things happen on top of it, it holds a memory of what it sees. All of my work is kind of an invitation for you to investigate deep. An effort to showcase one etymology of a material.”

The assemblage of the artworks, visitor, gallery, and content becomes a question of connectivity that requires reciprocity, not representation, not permission. The artworks as bodies converse through proximity and contact. I tasked the artists with seeing shape as a question. The exhibition consists entirely of works in sculpture and installation, to create a spatial prompt for adaptation and to recognize these forms as exercises with the visitor in a sovereignty that is relational.

In my curation I envision abandoning proof. I am responding to a cultural fixation I have noticed on embodying resilience in order to prove wholeness. This exhibition’s format proposes that we embrace ongoing negotiation, to locate a commitment in the process of learning how to choose connective shapes. Agency in the form of friction can coax us towards social/spatial configurations that are still unimaginable. We cannot wait for our healing to happen to us. Here, sculpture has the task to interrupt, hold, and prepare.

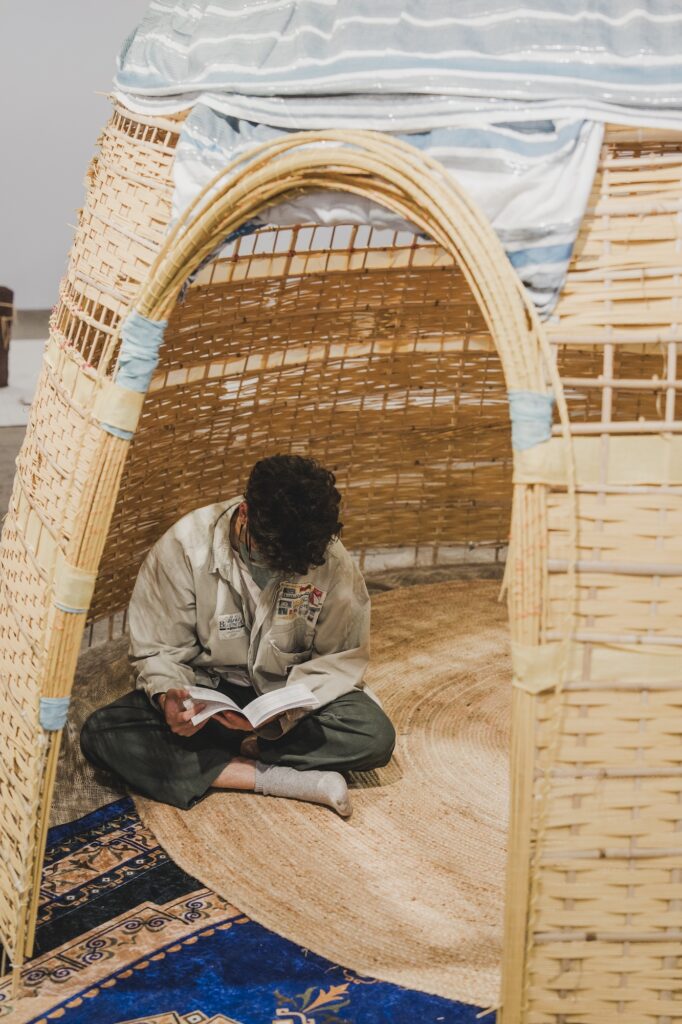

IFRAH MANSOUR

“There is a reason why my Aqals are imperfectly oval shaped. Sometimes the imperfectness of the oval creates a different intimacy.The door shape, the door positions, are discovered through the creation, I don’t plan where the door is and I’m happy to not know, and that seems deeply counterintuitive to people who live under continued violence. A lot of times our trauma forces us to always locate the door, find the door, be in close proximity to the door because you need to be fleeing.”

Sati: I would love to heal to a place where we just get to think about entrances.

“Someday we’ll get to a place where no one ever needs a door. You just have an entrance. You’re forever inviting–invitation is definitely a shape.

Our ancestors are always out there, encouraging us to live abundantly, to live abundantly without extracting or erasing another species. I think it’s possible, an abundance of deep relations with nature, and I tell this to my friends, as I’m watching my own community becoming deeply urbanized people. There’s something saddening to me when you watch your own community be removed from their nature-connection.

There’s a young person, oh I adore her so much, who has been telling me ‘Ifrah, you’re evoking our ancestors, you’re evoking our ancestors!’ For a long time I existed in some kind of limbo. The in-between. I’m feeling validated by my own community which I felt like might never happen. I felt like I would have to die for my community to validate my work. That feels like the friction of cultural acceptance, or our own peoples’ acceptance. Such a diaspora crisis…”

The wounds of enclosure remind us that we are products of something, the layers of worldly projects that rely on containment. Practiced refusal can take the shape of an ongoing conversation with our materials. BakiBakiBaki’s Octavia’s Hand and Cameron Patricia Downey’s Otherwise both commit to the lineages of using the leftovers–in Baki’s work it is the used paper bag, a utilitarian object in their connection to vodou tradition, yet loaded by its use as a pillar for colorism. Downey uses leather scraps precariously reassembled into a tapestry whose dimensions resemble the hide they came from. Breaking this material out of the waste stream also connects to a legacy of making use of what is at hand, making use of what is discarded by the careless captor. Like us, materials retain the conditions that shape them, residues of raw implication.

NAILAH TAMAN

“I think shapes hold a lot of power. Shapes have relationships with themselves that we don’t even know about. Similar shapes amplify each other. Whereas shapes maybe were asking questions of other shapes, but they have answered for themselves. And there’s knowledge in how the shapes are communicating with each other and how that affects the environment.I like keeping materials in the way I find them, you know, dirty setup. I just put them in a bag, I never wash the stuff before I combine it with other things because that’s how it came to me. And I should honor the way it came to me. And there is this reciprocity to it, you know, where sometimes it’s picking up trash, sometimes it’s picking up earthly treasures.

I once started exploring the cause of the glitter shortage. There’s this mystery: who used all the glitter? Or like why it, you know, where is it who’s buying the glit?

The glitter was not being bought, the machines were being utilized by the military to create ‘chaff,’ which is something that they drop from the sky that fucks with radars. They even did it in Minneapolis during the uprising. It kind of looked like snow or something, and it hit the ground and it didn’t melt. I can’t believe they use glitter against us. They do. So it is just a countermeasure using all the glitter and this work is also meant to be a countermeasure against those things.”

Reactive measures do not request foresight. The potency of this action can serve a propulsive middle. Nailah Taman’s Concretions Waiting to Happen intervenes in the concept of technology. It invites two people to connect through its openings, through sand, copper, glitter, and objects retrieved from many streets, they propose a sedimentary process of alignment, a fleeting togetherness that hints at the eternal.

Reflecting on this curatorial frame, my request to the viewer is not explicit. It bends to meet interiority. To address a direct current, a love’s pleading must also consider how we may live in orientations that adapt to the care and interventions required to oppose genocide, to refuse to replicate domination. My love, turn to the friction between foreheads in a promise, in the resistance of your words when you protect, at our feet on the different layers of ground, or our familiar paths and the chafing reminder of change. Within these moments I ask: would you choose this wash of togetherness and see it as more than speculation? I say: friction as a fertilizer is an unassuming treasure.

There is possibility in the kind of directionality that can only be found in relationship. We take up space, we fill that space with new orientations. As people oriented towards another pole of power, in the world around us we are disoriented. I see our task as taking shapes in which we can mark our collectivity through transformation. Our disorientations show us where to begin, where to put some truth into the ties we choose.

YOU SAY YOU LOVE ME AND I COMMIT TO FRICTION is on view at Public Functionary through September 28, 2024. More info →