Wunderkammer Redux (Or, An Unnatural History)

In the most elegant possible way, Kate Casanova's work across media sets out to make our habits of perceiving the boundaries between human-made environments and the so-called "natural world" a whole lot messier.

Kate Casanova’s Aftereffects: A Natural History, on view at Kolman and Pryor, is an elegant show. The work effortlessly spans a range of media, from digital scans turned archival pigment prints, to videos to clusters of small, white resin sculptures displayed on custom-built light tables. Always thoughtful, the artist continues her ongoing investigation into how we, as humans, make sense of our surroundings, a.k.a. “the natural world.” At a time when our myths of nature — invariably romantic and rooted in a deep sense of separation between ‘the environment’ and humans, nature and culture — have started to fail, such an inquiry is both necessary and urgent.

Casanova broaches these questions in a visual language that is characteristically controlled, steeped in a certain cool that covets precision. But this restraint results in a curious tension with the ideas of the work, where categories of natural history and conventional distinctions become porous and unstable. In the most elegant possible way, Aftereffects sets out to make our habits of perceiving the world a whole lot messier.

Casanova’s art has explored similar conceptual terrain before. In her Mushroom Chairs, dating from 2011-2012, the artist re-upholstered a series of chairs from different time periods into sculptures that hosted various species of mushroom: pink oysters emerged from a brocade-covered Victorian, lion manes from mid-century modern. Stylish objects created to support the human body were transformed into habitats for life forms as alien as they come. Most fungi live underground in complex symbiotic systems, subterraneously stretching their rhizome. Only their fruiting bodies pierce the surface, raining minuscule spores that expand the organism’s reach. Casanova’s chairs, aside from being incredibly fun to look at, effectively suggested an edge of the posthuman: as relics of an unspecified aftermath, they seemed to offer material glimpses into a possible future when organisms other than human were feeding off the furniture.

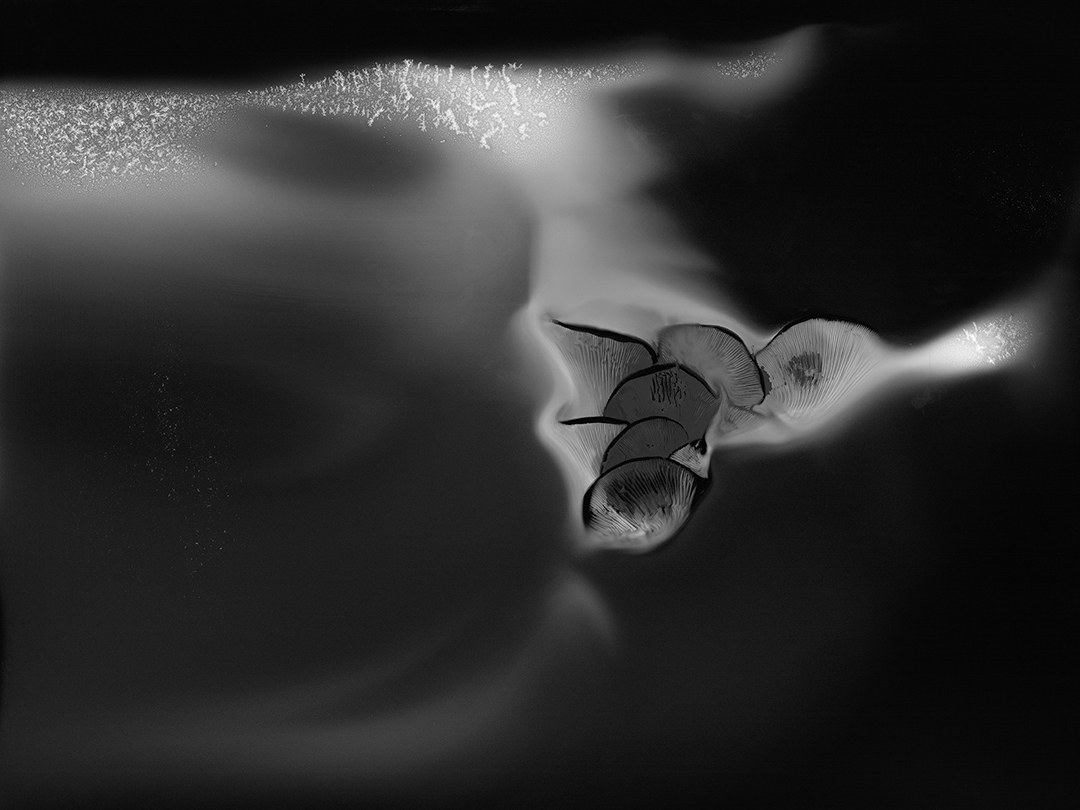

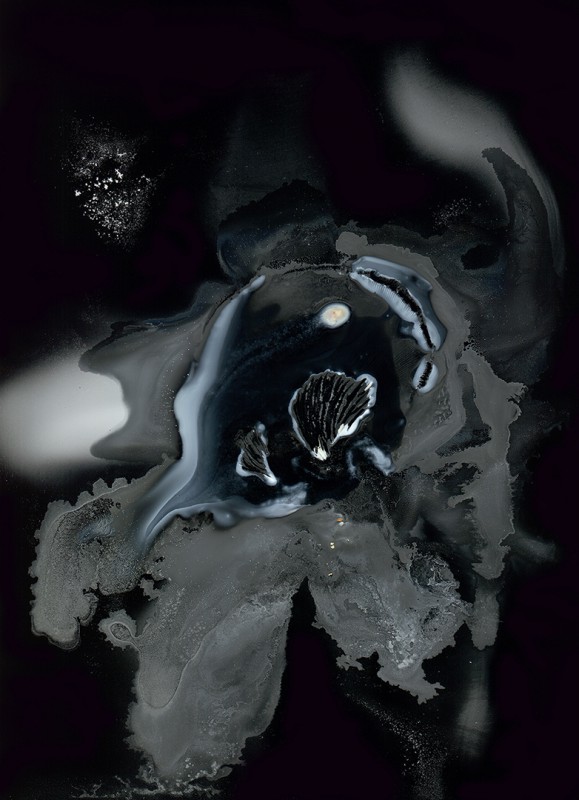

Aftereffects still relies on fungi to investigate natural history. In a series of digital scans, Casanova captures spore prints of a number of species. Used for identification purposes in foraging, spore prints create a kind of after-image of the patterns found on the underside of the mushroom’s cap. Pores, ridges, lamellas are outlined in the fine and, at times, colorful organic dust shed by the mushrooms. Eerily beautiful, the scans — Dispersion #1 through Dispersion #9 — capture the ephemeral organic arrangements. Some, in black and white, are reminiscent of X-rays, illuminating the interiors of creatures or structures (it’s deliberately unclear) that defy all attempts to fit them into the categories of natural history. Other scans, as a result of more moisture, include glowing halos and areas of pale blues, which lends them a quasi-mineral quality that suggests geodes and mollusks alike.

Kate Casanova, Dispersion #5. Archival pigment print of oyster mushroom spores, 2015.

Silent Things (detail). Photo: Bernadette Pollard

Casanova courts these confusions. As a family, fungi often defy neat distinctions, such as “plant” or “animal,” “flaura” or “fauna.” Slime molds move. Puffballs are polyphyletic assemblages: they may look like they belong to the same evolutionary branch but developed from different predecessors. Morels sprout only when their symbiotic relationship to the ash with which they live is threatened. Mushrooms are just plain weird — and hence, the epitome of unreliable categories and conventions in natural history. Mushrooms’ refusal to fit neatly into categories makes them particularly attractive for the artist.

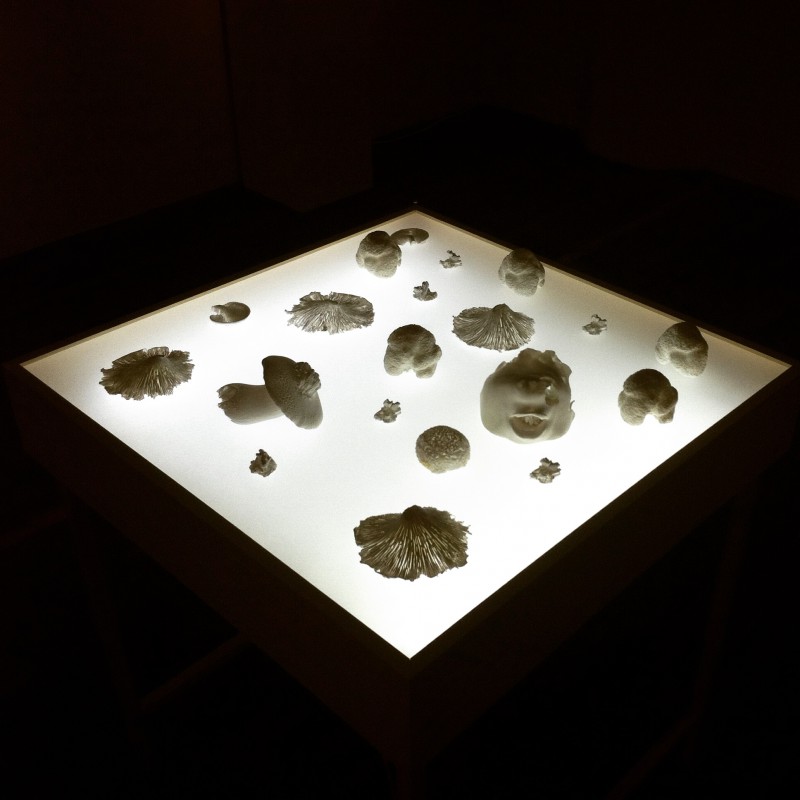

On three custom-built light tables, Casanova invites us to take a close look at resin sculptures of fungal bodies. The objects are stripped of color and juxtaposed with equally pale casts of small crystal clusters and plump caterpillars. Their bleached state heightens the sense of strangeness. What unites the array of specimens is that all have been arrested in mid-process: no metamorphosis for the suction-footed caterpillar, no spores to spread the mushrooms’ genetic information, no more tectonic pressure to cause crystallization. Titled Silent Things, this wunderkammer redux invites us to suspend the kind of categorical thinking we are so fond of and to wonder instead at the shared principles of emergence and transformation visibly halted here.

Amid the material snapshots, one object stands out: a partial cast of a human head, slightly distorted and verging on the porcine, crystals sprouting between its dilated lips. As if caught in mid-metamorphosis, the grotesque head-as-geode suggests a radical shift in point of view. What if, instead of assuming human beings are the planet’s privileged movers and shakers, we entertain a slightly less anthropocentric fantasy for a moment: following Manuel De Landa‘s and Vladimir Vernadsky‘s unorthodox take on evolution, biological creatures, including humans, are merely muscly tools in the service of minerals eager to find novel ways to redistribute across the globe. What if we consider, along with Vernadsky, that “we are walking, talking minerals”?

Casanova’s Silent Things harbor such stories. In their pale glow, they emanate a strange sterility, an elegance of parched bones. These not-so-silent things tell an un-natural history. They arrest not only organic and mineral processes but also halt habits of thinking, of writing natural history. How we look at what we call ‘nature’ is, after all, a part of cultural history. The show’s very title, Aftereffects, alludes to the delayed consequences of the way we have been looking.

One of Casanova’s sleek displays features casts of a fat, white caterpillar on its back right next to the upside down cap of a mushroom, its fans exposed, edges frayed. The combination is suggestive: When Alice stumbles her way through Lewis Carroll’s wonderland, her out-of-control shrinking and growing throws not just her her size but her perspective on the world into a state of flux. Thus she finds herself conversing with a hookah-smoking, telepathic caterpillar perched on a mushroom, a critter that eventually helps her regulate her proportions and point of view: clearly, neither can be taken for granted in wonderland. (It is an oddly delightful coincidence that Casanova played that caterpillar in a grade school production.)

Spread on a light table, as if demystified, the objects take on the air of precious relics. Yet they steer clear of the familiar tones of nostalgia and lamentation for the purportedly lost capacity to wonder in the aftermath of scientific dissection. Yes, perhaps a certain point of view has ossified beyond the tremors of doubt and masquerades as “natural” and “given.” Silent Things invite us to trouble this set of mind. But more importantly, these things cultivate a sense of wonder that grows in the shadows of facts, deepening and lengthening as they do.

Pools is a case in point. Taped to clear panes of glass, small square drawings of various sizes present a collection of amorphous, amoeba-like shapes. Some seem to sprout blobby tentacles, others are reminiscent of geologic phenomena or cell mitosis: together, the disciplined grid suggests a very odd taxonomy of becoming, hovering between macro and micro, conjuring a delicious uncertainty. What exactly are we looking at? The pieces of white tape give the display a provisional quality, as if other arrangements were also possible: once again, a merely momentary arrest. The series maps the results of interactions between a glue-coated substrate, charcoal dust, and water. The artist’s intervention in these minute material dialogues consists of dabbing up excess water after the black dust has settled. Instead of imposing human agency at every step, Casanova is set on letting the materials — whether water, glue and charcoal, or spores and scanners — do their thing.

As the artist’s hand recedes, the agency of matter asserts itself. Untitled (Peephole) records the beam of a scanner passing over a still life of mushrooms nestled on the glass bed. The reflection on the scanner bed creates the illusion of orifices, organic canyons whose interiors are momentarily illuminated by the light’s movement before fading into impenetrable darkness. Through the blind eyes of a machine that is impervious to their eerie beauty, luminous forms emerge: glowing fans of fungal bodies in hues of pink and purple. Unfolding, in a similar way, relies on mirror images in its time-lapse recording of pink oysters’ magnificent growth. From a nigh-invisible speck of spore, fleshy horns sprout, followed by larger protuberances that curl into lips and shelter the fantastic lamellas that rib the fungi’s ground-facing side. As soon as spores begin to drop, the sequence reverts, and an equally mesmerizing shrinkage follows. Spaced between differently timed twin clusters on both sides of the screen, the fungi’s emergence and retreat alternate in a slow sway reminiscent of aquatic life, undulating in unseen currents. In both videos, Casanova harnesses digital technology to make visible the very strangeness of fungal forms and reproductive processes.

Despite its elegance, its undeniable coolness, Aftereffects is also an intimate show (and not just because we see mushrooms procreate). Perhaps it is the idea of “radical intimacy,” championed by Timothy Morton, that radiates through Casanova’s practice, the “strange strangeness” that springs from the most intimately familiar things and people, if we take the time to really look. Blurring the boundaries between mineral and mycological, animate and inanimate, transgresses the divisions natural history has relied on for such a very long time. What happens when these clusters and categories touch?

But while Aftereffects is conceptually and aesthetically sophisticated, I cannot help but yearn for more than a subtle dash of disturbance from Casanova. The humor, taste for grotesquery, and palpable irreverence so evident in earlier work, such as Green Screen, Sub Lingua, and Vivarium Americana fade in Aftereffects, with the notable exception of the strange head-geode hybrid. Put simply, the quirk quotient is lower here than in her earlier works. I, for one, miss the oddity Casanova is so capable of.

Related exhibition information: Aftereffects: A Natural History, runs February 28 through April 11, at Kolman & Pryor Gallery in Minneapolis.