The Center and the Edge

Videographer and filmmaker Kevin Obsatz reflects on his experience documenting Karen Sherman's latest work, "Soft Goods," on light and darkness on stage and off, and the deeply collaborative work of pulling together a performance.

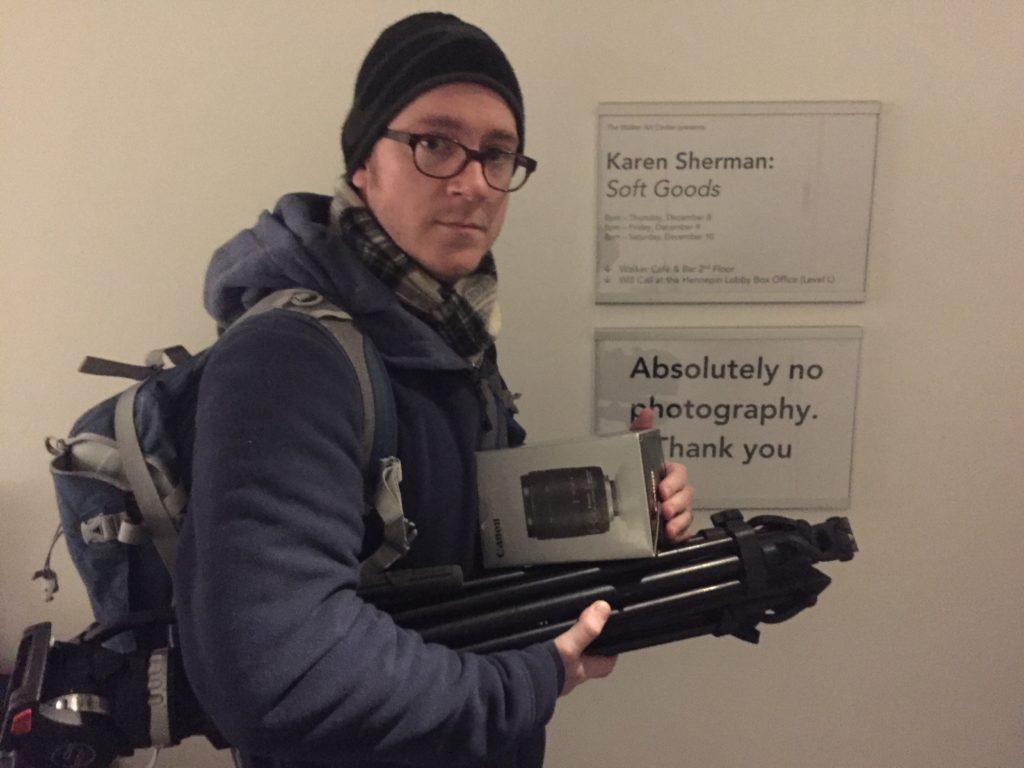

I’ve been a videographer for performance in the Twin Cities for more than a decade, documenting dance and theater at almost every non-union venue in town. The Walker Art Center’s McGuire Theater has its own in-house video people, but occasionally I shoot a show there, particularly when a choreographer wants more documentation than the Walker offers – more cameras and/or more nights of a run.

Karen Sherman hired me and another videographer, my colleague Ben, to shoot two additional performances of her piece, Soft Goods a few weeks ago, Thursday and Saturday (the Walker team filmed on Friday), and I’ve been thinking about it ever since. Rather than review the show or try to describe it in a comprehensive way, I want to share my experience documenting it, which seems appropriate in spite of my relative lack of knowledge of either choreography or theater terminology. The piece focuses on the technicians rather than the dancers in the cast, though there are no videographers officially featured.

For the Thursday performance I was set up at the back of the house, and the mood in the space seemed different than usual. I was stationed next to the sound technician, and in addition to helping me out with an XLR feed direct from the soundboard, he wanted to warn me about an especially loud section, and talk through a particularly tricky moment where the sound design travels around the space in a circle, through eight channels – which my mono input wouldn’t be able to track.

Beyond that, he was chatty. There’s a section in the piece where the light travels over the audience, shining directly into my camera, and I remarked that I actually like lens flares, which led to a short exchange about JJ Abrams’ first Star Trek movie, where he reportedly drove the camera department nuts by standing just out of frame and shining a flashlight into the lens, scene after scene.

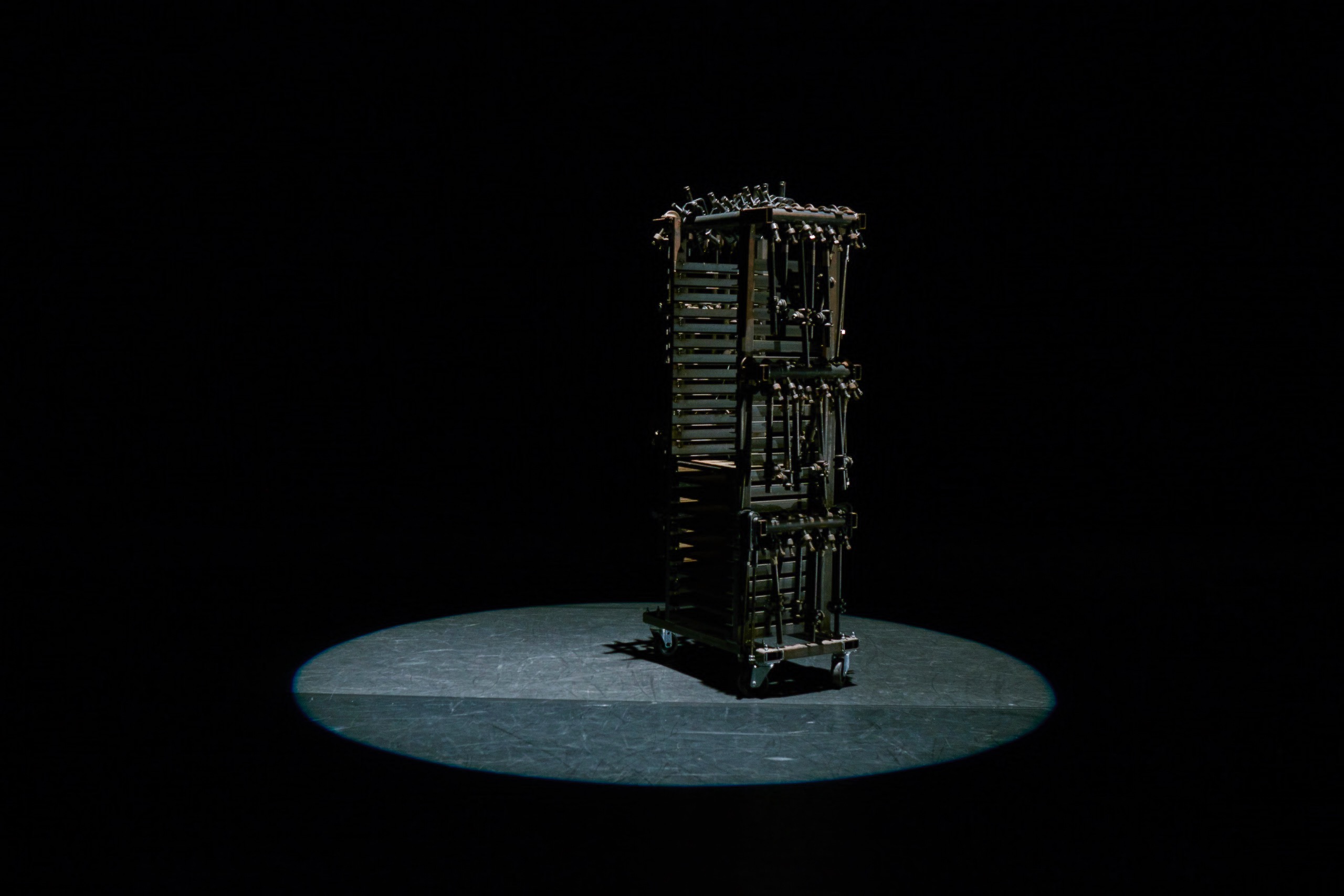

Soft Goods starts with a “pre-show” section while the audience is entering and finding their seats. The stage is cluttered with equipment, and technicians move around purposefully checking things, moving things into position, and bantering back and forth. At some point, mid-pre-show, the whole lighting grid descends to the crew’s eye-level on booms, so the crew can check the connections, position and intensity of all the lights.

The lighting board takes up several rows of seats in the middle of the house – this is where it’s usually positioned during tech for a show, before being evacuated to an enclosed booth at the back during the performances – usually, but not for this piece. At some point the banter fades and we’re left with only the grid of lights near the floor, shining bright pools of light onto the black marley stage surface, turning on and off in a slow sequence. Then the booms rise, one after another, drawing our eyes upward, and the crew exits upstage.

The stage is empty for a long time, and nothing happens, except, way up high in the center of the grid, there’s a single light coming on; it’s not a traditional theater light, either, I don’t think – not the kind that can be carefully controlled from a light board. It’s more like a streetlamp (I want to say sodium vapor, but who knows?), which sparks on but then takes a longer time, maybe 30 seconds, to reach its full intensity.

So we, in the audience, are left with that one light, slowly growing brighter and brighter, gently insisting on itself as the focus of our attention, as we sit, wait, breathe, wonder what’s coming next. Then people, the crew, re-enter and the banter resumes, none of them noticing the light way up high that drew and held our attention in the audience for what felt like such a long time.

Again and again, throughout the show, there are moments like this, sometimes gentle and sometimes more dramatic, where our attention is lifted from where we expect to be directed to look, and re-placed somewhere adjacent or above. We see a figure in light, and that’s what we first focus on, but then our attention is drawn to the edges of the light, or up the beam itself to the source, the apparatus making the light, and the person directing that light across empty space to where it will land.

There is a dance happening, and a kind of comedic rivalry between the technicians and the dancers, but likewise the dance is continually being moved out of the center of our frame, to the edges. The dancers work, and their work is taken seriously, but the piece they’re working on seems notably mediocre, on purpose – the work, the rehearsal, the relationships between the dancer and the occasionally-seen lighting designer and choreographer are the interesting part – not the artistry of the movement itself.

The shape of Soft Goods feels soft, spacious, and slow to me – only in retrospect did I realize that it is sort of chronological, leading from the arrival of the dancers through a warm up, a rehearsal and eventually a “performance” of whatever it is they’re working on. I don’t consider myself a theater tech, but I thought I recognized the pace of long days of preparing for a show, where there are extended stretches of time during which it seems like nothing is really happening, and yet everyone is working, alone and together, to complete the necessary tasks that make a show happen.

The techs are real techs, not dancers pretending to be techs, and it wasn’t until my second time seeing the show that I realized they never dance – they never do anything un-tech-like, until one moment very near the end, at a kind of climax of the piece.

The dancers are in full costume (black plastic garbage bags) and stride seriously about upstage, until a solid black rectangle about the size and shape of a movie screen descends from the sky and blocks them completely from the view of the audience – after which we only see their shadows gesticulating dramatically around the stage. We realize that we’re backstage now, with the techs, the “stage” has been flipped 180 degrees.

The techs prepare for something in a focused way, and then various lightweight props begin to soar over the black rectangle, crashing to the ground: a butterfly net, a toilet scrubber. The techs dart around like tennis players returning serves, gathering them up, piling them in a corner of the space. The dancers periodically emerge around the sides of the rectangle, too, urgently demanding something – retrieval of a tossed prop, help with a costume change.

In the midst of all this, one of the techs stops participating, stops helping, shuffles to the center of the space, slowly raises his hands… and his non-participation becomes something more, something bigger than just a man overwhelmed, or fed up, or simply done with his role.

I think, at that point, everyone else departs and he’s left alone, and only then does he start to dance – an awkward, simple, leaping kick, back and forth. Whatever it is, it’s not for anyone else, not for an audience; it’s just him moving in a way we haven’t seen before. Things start to fall out of his pants, it’s hard to tell what exactly – could be coins, or nuts and bolts… something heavy and metallic, ringing on the rubberized marley of the floor, making a huge mess no doubt as the lights cut out. I believe he’s the last person we really see in the piece – everything that’s left, after that point, is light.

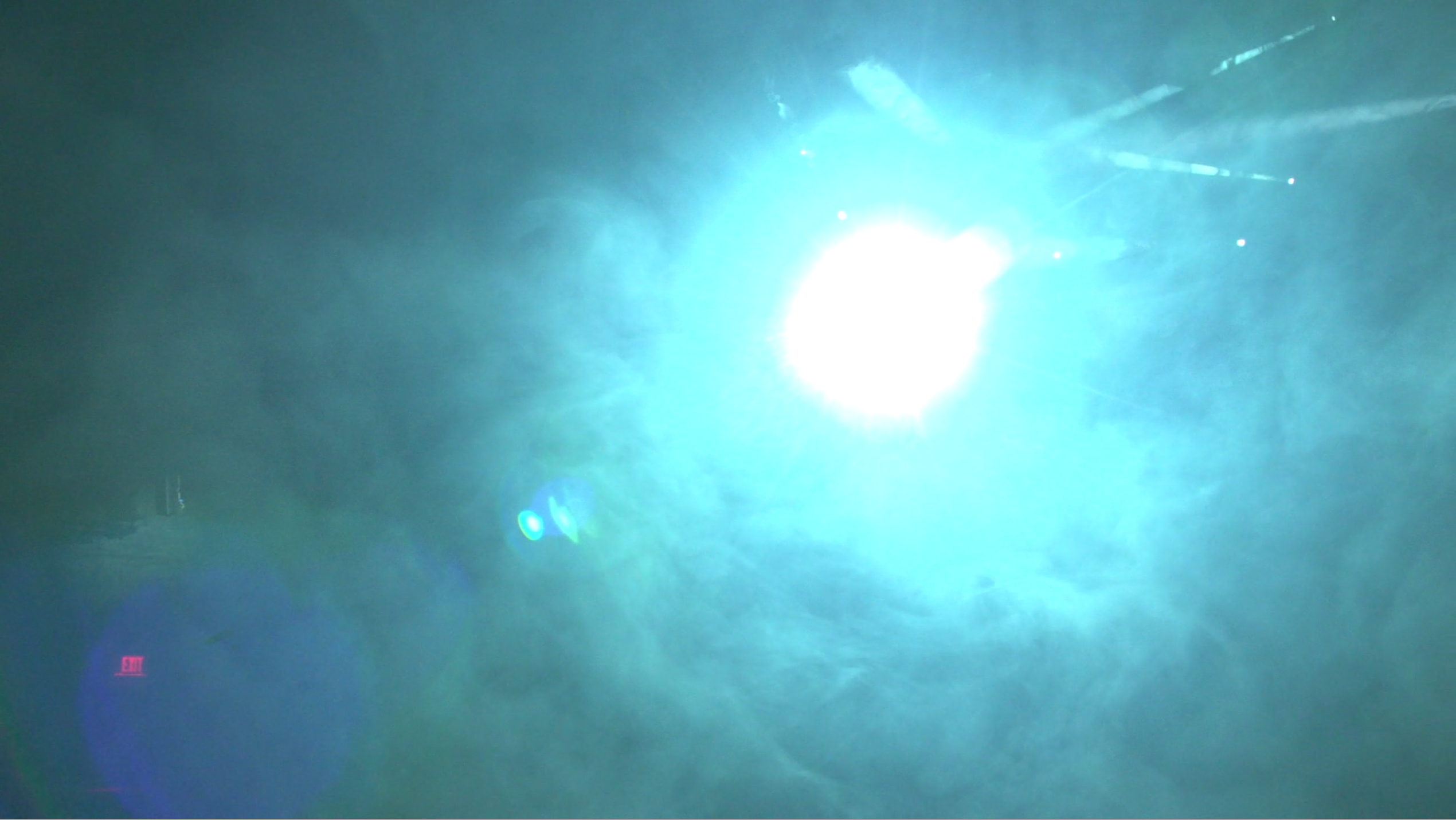

The last section is a choreography entirely of lights and thick fog. Five spotlights travel up the back wall in an arrow formation and then explode outward into the house, shining all kinds of crazy patterns and colors through the fog, onto the audience, directly into our eyes and our cameras.

It seems like a small thing, a difference of a few degrees in the angle of a light, determining whether it hits a dancer or a wall, or a cart full of equipment, or a toolbox. But the distance from the center of the spotlight to just beyond the edge is actually vast and profound, and encompasses an entire spectrum of value.

The second time I shot the show, Saturday night, I was near the front on the side of the house, and during the light and fog section I was able to get some beautiful shots of the audience, all lit up with blues and greens. I was also able to mimic that shift of attention, travelling from the subjects illuminated by the light up the beams (visible in the fog) to the sources themselves.

At one point near the end of this section, my camera had just reached the light source high above when I realized it was shining directly at me in my spot, near the front on the side. The light rested on me for what felt like a long time, and we kind of stared into one another’s mechanical eyes. My shot was exhilarating to me, the light at the center of the frame in a halo of flares, ringed by swirling fog. Not unlike, I suppose, the classic formulation of the near-death experience.

“You had a moment,” said another choreographer friend, after the show. I didn’t realize until she said this that I had been lit, that the light had been illuminating me filming it, for the sake of the rest of the audience – that in that moment I was performing in the piece and documenting the piece, in a strangely personalized blurring of the boundary between the inside and the outside of the performance.

Though I haven’t listened to any interviews or read about the piece, I’ve heard that Karen Sherman has been vocal, in interviews and press materials, about the role that recent suicides of stage technicians played in the making of Soft Goods. It wasn’t until my second viewing that this became really apparent to me: the act of seeing the crew, really seeing them not just as professionals, but as complex, beautiful and flawed human beings, who are physically present though often hidden, in the space, making the art alongside the performers. The second time it felt all about death to me – in particular, a connection between Death and Light.

We often don’t see light, we overlook it to focus on where it’s shining, what it illuminates. In the performing arts, we often think of it as something essentially technical, a tool built from electricity and metal and glass, that we can direct and control. And yet, in a profound way, light isn’t ours. It’s willing to cooperate with us in the making of art, but it’s far more vast and powerful and mysterious than our rudimentary tools for making and shaping it.

After our first shoot, my co-videographer and I packed up our stuff and headed out, tired from a long performance and not planning to mingle on our way through the crowd. As we passed through the stage door, we found ourselves next to Philip Bither, the Walker’s Performing Arts Curator.

“How did that go for you guys?” he asked. I looked at Ben, Ben looked at me. “It went great,” I said. “Seems like a tough show to shoot,” said Philip. We agreed. “So, did Karen hire you guys?” “Yeah,” said either Ben or I. Our conversation went on awkwardly for a few moments more, then he said goodnight, and we left. “That was weird,” said Ben.

I’ve known who Philip Bither is since I was an intern in the Walker Film/Video department in 2002, when our office was next door to the Performance department (pre-expansion). I’ve documented other performances at the Walker, I’ve shot probably dozens of other shows that he has been involved in, including the Momentum series co-presented by the Walker and Choreographers’ Evenings at the Walker. I have created video elements for live performances that I know he’s seen; I won a Sage Award for Design last year, and I’ve met him multiple times at various parties and events over the years.

But this was the first time in those 15 years that he ever initiated a conversation with me, however brief. Now, I don’t begrudge him that – I don’t feel slighted by the fact that he doesn’t know me. He’s a busy guy who meets tons of people as part of his job, and I don’t expect him to be aware of me either personally or professionally. I like my job as a videographer, and I feel well-compensated; I wouldn’t do it otherwise. I don’t expect a lot of recognition, outside of the occasional word of thanks from a choreographer or dancer who appreciates my work.

But, I think it’s pretty clear that it was the show that made Philip Bither just a little bit curious, and willing to initiate contact with Ben and me. If we had been coming out of any other performance I suspect all three of us would have kept to ourselves. But Soft Goods managed to gently shift his attention and perception to the point where it included an awareness of us videographers, the fact that we exist, that we participate in what he does, that we might even be really good at what we do, and that our contribution is meaningful to the whole enterprise.

That moment after the show underlined the important and (to me) subtle political dimension of Sherman’s piece. It seems like a small thing, a minor distinction, a difference of a few degrees in the angle of a light, determining whether it hits a dancer or a wall, or a cart full of equipment, or a toolbox. But the distance from the center of the spotlight to just beyond the edge is actually vast and profound, and that space encompasses an entire spectrum of value, from importance to obscurity, from intense scrutiny to total ignorance, from deep emotional investment to utter ambivalence, and yes, from bright, messy, leaping and churning life (and who knows, even afterlife) all the way to the cold, dark void of absence and death.

Noted performance details: Karen Sherman’s Soft Goods was on stage in the McGuire Theater at the Walker Art Center in early December, 2016.