Paradoxes: Frank Big Bear at Bockley Gallery

Lightsey Darst reviews the show "Portraits 1997-2006" at the Bockley Gallery. This rare show by Frank Big Bear shows a new subtle complexity in his work

Frank Big Bear has put the first months of 2006 to good use, coming up with enough work (all but two works in this show are from 2006) for a showing at Bockley Gallery.

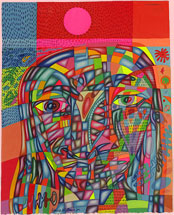

With “Portraits” as a title, you might expect works that concentrate on various human faces or qualities. Instead, in these works, the flat, simplified faces, all with the same features, become lost in the images’ bright colored-pencil segments. These fragments of color create both central imagery and the surrounding field, and they, are rich with tiny, simplified animal forms—wolves, birds, skeletal fish.

These gem-toned, hectic works are little more like portraits than a crazy quilt would be. But this tension between name and object is productive rather than frustrating, leading the viewer into the work. The faces are mostly a little larger than a real-life face. They fill up the small picture space, and they have large, staring eyes, the expression of which might be fear, weariness, warning, or attention; the rest of the features, and especially the tell-tale mouth, are lost in the vivid patchwork of shapes.

The ambiguity of expression leads the viewer in contrary directions: are the surreal backgrounds, intense with animal life, the vision the dreamer sees? Or are we the ones granted a vision, able to see the face in its true context (even if the face itself does not perceive this)? The animals, the dense fracturing, seem simultaneously to weigh upon and to relieve the faces. Is this connection to nature and setting a blessing or a curse? Are these faces weighty with responsibility or bleak with their loss of free will? While individual works, by their titles and prevailing colors, suggest particular moods (desperation, as in “It’s a Good Day to Die,” or peace, in the calming tints of “Impressions of Autumn”), the fruitful mystery of what is being depicted—realization? dissolution?—and where we stand in relation to the depiction—viewer or participant?—remains.

The fractured images present another problem for the viewer—where to stand. Too far from the image and you won’t see the detail, the workmanship, the tiny totemic animals; too close to the image and the whole becomes lost in its fragments. In three larger works (two of which are several years older than the rest of the work), a clearer division between face and background, a greater sense of perspective, makes the images happily pop into a new focus once you’ve backed up far enough. But the smaller, more claustrophobic works refuse to yield to vision; something is lost (and gained) at every vantage point. Sometimes I enjoyed this difficulty—it’s like looking into a river to spot the fish; at other times I wished the images would yield more on the large scale.

But to seek an authoritative vantage point or interpretation is largely to miss the work’s vitality, its improvisatory brilliance of shape and color. Big Bear overlays natural flame or bubble shapes with sharp spikes and curving diagonals, so that the image becomes a mosaic of differently shaped bits, as if we were looking at it through several fences. Totemic animal shapes crawl or fly in wild variety; finding them all would keep a child happily occupied for an hour.

Color is equally various and unpredictable—in most works. Where Big Bear chooses a prevailing color scheme (“Virgin of Fire”) or a less fine patterning (“Autumn’s Wind”) the work suffers. In the majority of works, though, Big Bear’s virtuosity gives the viewer the same instant pleasure and desire to gaze as stained glass windows, pieced quilts, and mosaics do.

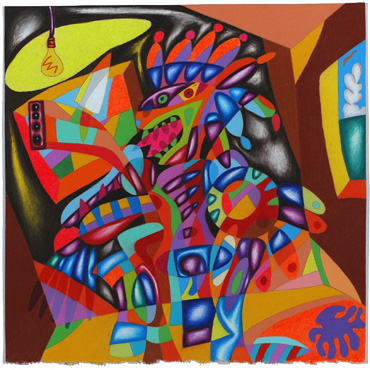

The scatter of form and color is at its most satisfying in the three small (9 inches by 9 inches) images of the “Trapped in Paradox” series. Here the fence-like overlay is mostly gone, but the figures—men, maybe, seated in chairs—themselves are composed of shapes and pieces that seem to be struggling away from each other. The animal blends with the human here; one figure appears to have a gaping fish-skull for a head. The chairs might be lazy-boy recliners or airline seats; the figures are looking, wide-eyed and open-mouthed, into TV sets or open windows.

Despite their modern surroundings (a lightbulb dangles low over one) and their own disintegration, the figures grasp elements of traditional regalia—a spear, a feather-edged shield, a top hat, a headdress. What’s going on here could be reduced to a statement about Native American life continuing and clashing with modern American life, but that interpretation belies the work’s complexity. To begin with, there’s nothing empathetic about these figures; unlike the other figures in the show, they don’t have large human eyes that invite identification. Instead, there’s something fierce, almost triumphant, about these conglomerate creatures. Is the image an exorcism? Is the figure a new hero, perhaps a trickster for the technological age? Pleasure, too, undermines any strict scheme. Magenta with straw yellow, dirty lime beside black—whatever the meaning of the image, the color tells a story of unlikely harmonies.

“Trapped in Paradox” might be an appropriate title for the entire show—except that Frank Big Bear isn’t trapped in his paradoxes, but rather playing with them, exploiting them. The tantalizing, mysterious images here leave the viewer wondering what Big Bear will produce next.