Magic and Hard Work: Alec Soth at MIA

Michael Fallon interpreted Alec Soth's work in the Minnesota Artists Exhibition Series Trialogue at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts. Trialogues are sponsored by the Visual Arts Critics Union of Minnesota (VACUM), of which Fallon was a founder

Have you ever noticed that certain people seem blessed? Some years ago, while I was in the Peace Corps, the universe always shone on a guy named Billy, despite his obliviousness to the normal rules. If he decided, for instance, to take a sudden weekend trip to the backwoods of Turkey, and he had no plan other than to enjoy himself and see what could be seen, nothing bad ever happened. He was never mugged, nor thrown into prison, nor kidnapped and held for ransom. Instead, on his first day in the country he would meet the regional mayor or other such person, who’d take him home to meet an eldest daughter with whom he’d spend seven satisfying days being fed grapes and local bread.

I hate these sorts of people, don’t you? They are holy fools, real-life Elwood P. Dowds or Forrest Gumps who are not at all like the rest of us. They are not constrained by the conventions that hold normal folk in check. Life is a hard and bitter event, but they receive only blessings.

Alec Soth is such a person. Speaking artistically, anyway, people and good fortune seem to flock to him as a matter of course. Soth—as he mentions on the gallery video, and as I’ve seen in person—is able to bend normal rules in order to make visual magic happen. That is, he can convince busy and overworked people to perform superhuman feats of endurance and forbearance, standing or sitting in front of him as he makes endless adjustments to his camera. And you should know this: Soth’s process of shooting is very complicated and time-consuming. His R. H. Phillips and Sons 8×10 Compact camera must be reconstructed on each use from a variety of parts, and it uses large and expensive negatives that slide one at a time into the camera’s back. The camera’s lens is particularly sensitive to variations in light and has a shallow field of focus that causes the artist to be very fussy in taking a picture. Soth told me several years ago he was lucky if he managed to make one or two exposures on a given day of shooting with this camera.

Soth would have us believe that it’s precisely this ordeal that allows him to peer into the souls of strangers. That is, Soth says because he hides underneath a hood and stares at the ground glass at the back of the camera rather than at his subjects, they are not aware of his gaze and they become less self-conscious, more open. So that while people normally are guarded against each other and skeptical of encounters with strangers, hiding behind masks of general indifference, with Soth they unmask themselves.

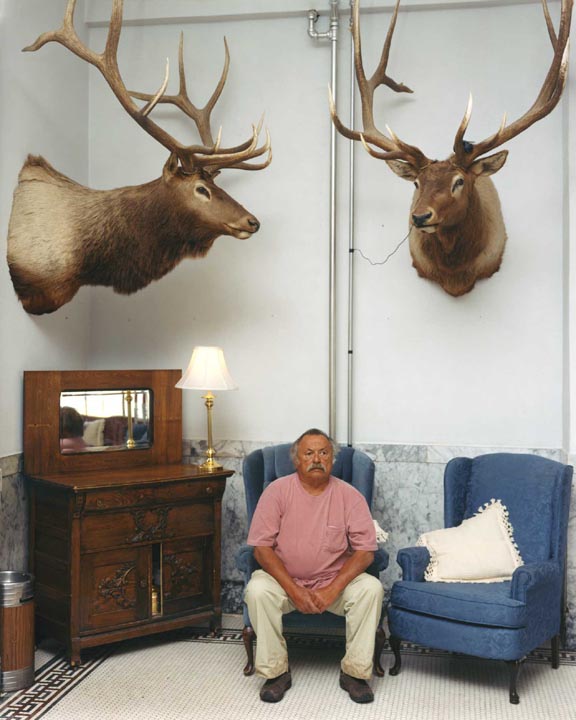

Whatever the reason for it, we can see the unmasking in his images. The best works in “Portraits” are magical and poetic revelations of a subject’s naked psychological state. In “Jim Harrison, Livingston, Montana,” for instance, Soth has coaxed the perfect light and composed the elements and details of the image—including the position of the subject himself–to reveal much more than is apparent. In a corner of a strange room the author sits small and tired, his cuffs dirty and face ruddy, on an old steel-blue chair. Overhead loom two large elk heads, whose expressions are more lively in death than the author’s in life. Oddly, a wired video camera rests in the horns of one elk, a modern element that contrasts with the throwback details of the marble wall, tile floor, well-worn antique bureau, and exposed pipes. The blue-white light of the setting, playing off the blue chair and the blue tinge in the marble wall, raises the warmly russet elk heads to a massive, iconic status, while the ruddy and pot-bellied subject is diminished compositionally to a state of spiritual isolation. And there is that matter of the subject’s glance off the left—what is he looking at? Is he uncomfortable? If he’s uncomfortable, why is he even sitting for the portrait? Nothing in the subject’s face can escape scrutiny, and the unguarded natural state of a human spirit is brought to paper by the peering, diamond-etching gaze of the lens of Soth’s camera.

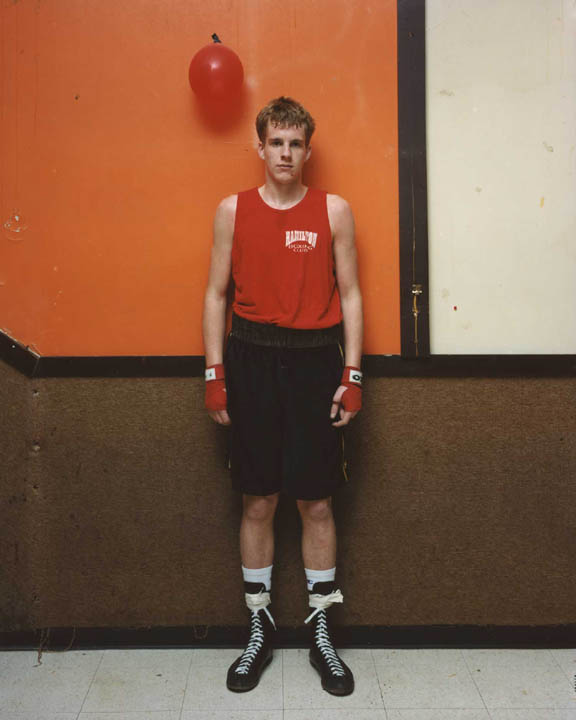

Another image I like for this quality is “Alex, Nicasio, California.” In it, a woman stands as though just discovered on a path. This image has the theater of a Renaissance painting, the girl a modern Madonna, inscrutable and visually perfect. Soth’s best images are often richly detailed and painterly, even symphonic, in their tonal composition, and this image is a good example. The young woman’s orange hair and orange lipstick play compositionally like grace-notes off the yellow-orange tinge to the leaves in the foliage on either side of the path and off the orange articles of clothing in the mesh bag she carries. As a counterpoint, the woman’s toenails, the mesh bag itself, and a gem on a necklace around her neck are all greenish blue, mirroring the deep bass notes in the rest of the dark blue-green foliage around her. What makes this image work is the point-counterpoint of complementary blue bass notes and orange grace notes. In “Daniel, Niagara Falls, Ontario” (2004), fugues of red—in a balloon tacked to the wall over the shoulder of the subject (a young boxer), a red thumbtack on the wall next to his left elbow, and a red shirt and red wrist wraps—provide a way to move through the image and discover a hidden story. Namely, the spots of red lead the viewer eventually to notice the faint hint of blood on the boy’s nostril and chin—details we miss at first glance—and realize this boy has just been fighting, which explains the strange, empty look on his face.

Of course, I was being glib when I suggested Soth is a blessed fool, as I know there’s more at work in his photographic practice than luck or divine intervention. In fact, Soth is able to draw people to him and convince them to work with him; his skills are so eerie that I once wrote he was a “used car salesman” of a photographer. I happen to know this because I was fortunate enough to go out on a shoot with him one summer and see his method in action. On a hot August Monday afternoon, Soth found a lonesome soul drinking at the end of a workman’s bar and began working to convince the man to sit for a shoot.

“I’m drawn to dreamer types–people who dream big,” is what Soth told the guy, whose name was John. “Something told me you were a dreamer.” When the subject finally agreed, the photo shoot itself took several hours and went through several phases. There was a steam-bath hot phase in the attic of the man’s house, where he was surrounded by rock posters, boxes of LPs, and clothing from the late 1970s. Soth did a lot of rearranging here, apologizing all the while as he repositioned posters, brought lamps forward, and moved other objects to make a new version of what was present before. John was gracious, saying it looked cleaner than it had in a long time. Later, after all this work and as the afternoon light began to die, Soth took afterthought photos of John downstairs in front of long, metallic-gold drapes. Soth asked him to hold an accordion that was sitting close by, and again began the process of taking light meter readings, positioning and repositioning the camera, and peering at the ground glass under the hood. This was when John was finally revealed—several hours after they had begun.

That it took that much effort and gumption on Soth’s part to get this one image is the real secret to his success. It’s not that the universe shines on Soth; rather, as with my friend Billy, Soth is able to achieve great things because he is unafraid to attempt them.